February arrives after a tough January for Los Angeles and its environs; if you haven’t been reading much, it’s understandable. Perhaps a few of the titles on this month’s list will encourage you to take a break if you can and explore different places.

Some of them, like turn-of-the-20th-century Manhattan, are bustling. Others, like contemporary Baltimore, feel a bit lonely, while Soviet-era ballet studios are competitive and redolent of sweat and tobacco smoke. The Seattle in which a computer genius grew up contrasts with the coastal logging town in a great director’s TV masterpiece. Happy reading!

FICTION

Victorian Psycho: A Novel

By Virginia Feito

Liveright: 208 pages, $25

(Feb. 4)

Winifred Notty arrives at Ensor House as a governess with a secret, which would be enough for many a novel set in Victorian England. However, Winifred tells us immediately that in three months, “everyone in this household will be dead,” which includes her charges, Drusilla and Andrew. Winifred might be the smartest, wittiest and most brutal psychopath to grace the pages of a comedy of manners that turns into a horror show — all in an age rife with repression.

Mutual Interest: A Novel

By Olivia Wolfgang-Smith

Bloomsbury: 336 pages, $29

(Feb. 4)

When Vivian Lesperance, who knows she’s queer, decides to marry Oscar Schmidt, who is still closeted, she does so with the knowledge that she and Oscar can turn his family’s soapmaking concern into big business — and that perhaps they can also have an unconventional household that allows for them both to love as they choose. As their company grows, so does Oscar’s love for their colleague Squire Clancey; eventually everyone will have to acknowledge limits.

Brother Brontë: A Novel

By Fernando A. Flores

MCD: 352 pages, $28

(Feb. 11)

Despite its title that harks back to 19th century fiction, this new novel from Flores takes place in a near-future dystopia and continues his wonderfully nutty style. It’s 2038 in Three Rivers, Texas, and Mayor Pablo Henry Crick intends to enlarge his neocon agenda, having already outlawed reading (he distributes book-shredding devices to the city’s disaffected youths). When two of the last literate inhabitants rise up, chaos ensues. Thank goodness.

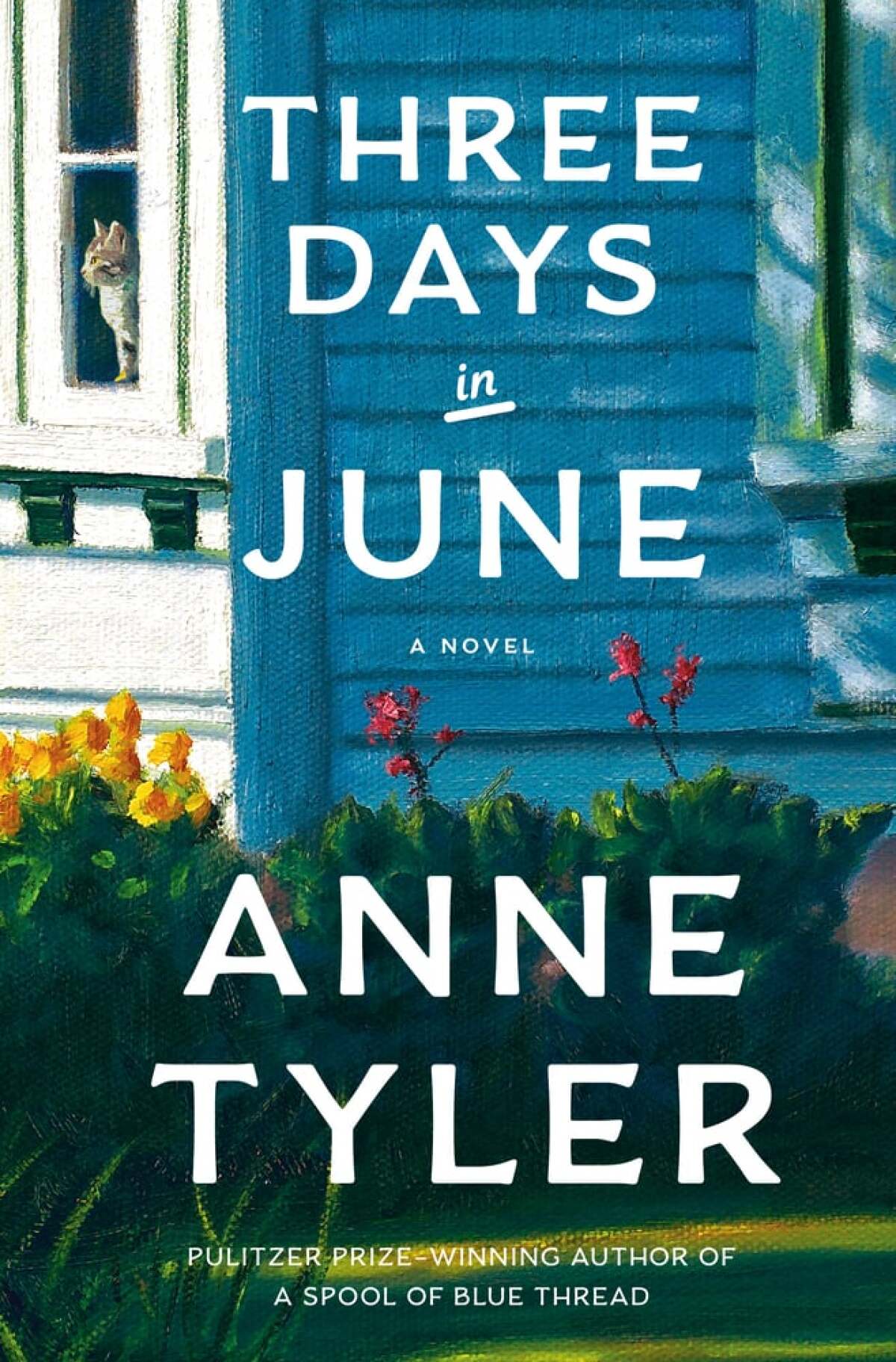

Three Days in June: A Novel

by Anne Tyler

Knopf: 176 pages, $27

(Feb. 11)

The bad news: Anne Tyler can’t possibly write forever. The good news: Her latest novel proves that she’s still inimitable and still providing fresh perspectives on ordinary people whose lives may be quiet but hold surprises. Here, a dissatisfied private-school teacher, Gail Baines, faces her daughter’s wedding, her ex-husband and a rescue cat. By the end of this deeply compassionate and very witty novel, several lives will have changed.

Maya and Natasha: A Novel

By Elyse Durham

Mariner Books: 384 pages, $30

(Feb. 18)

Twin sisters born at the same time as the Soviet Union both pursue dance training at the feeder school for the great Kirov Ballet. However, only one member of a family is allowed to take part in tours outside the Iron Curtain, and when Maya and Natasha realize they will be separated, one betrays the other and causes a schism that echoes through the rest of their lives. Durham’s careful writing about dualities feels like delicate choreography.

NONFICTION

Bibliophobia: A Memoir

By Sarah Chihaya

Random House: 240 pages, $29

(Feb. 4)

Some books, says author Chihaya, are “Life Ruiners,” by which she means they split open our received perspectives and make us question everything from our families of origin to our dreams for the future. Nonetheless, she built a life on books and criticism and teaching at an Ivy League university. When a nervous breakdown resulted in hospitalization, the author found she could no longer read her own life. Her account offers an urgent look at mental health and intellect.

Source Code: My Beginnings

By Bill Gates

Knopf: 335 pages, $30

(Feb. 4)

Caveat lector, especially if you’re a lector who wants to read only about the history of Microsoft: The subtitle is there to remind us that this book covers Bill Gates’ childhood, upbringing and secondary education. It ends just as he decides to leave Harvard and start Microsoft. He does plan to write two more memoirs, so those Microsoft-history stans should be satisfied. But first, it’s worth reading about his challenges as well as his endless curiosity.

David Lynch’s American Dreamscape: Music, Literature, Cinema

By Mike Miley

Bloomsbury Academic: 288 pages, $34

(Feb. 6)

David Lynch, a true auteur who died Jan. 15 at age 78, leaves a rich and varied legacy well explored in this volume. Featured works include “Blue Velvet,” “Twin Peaks” and various collaborations. Miley, a film scholar, examines those and many other works as they affect (and are affected by) other great classics of American culture, from literature (“The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman) to mixtapes to the city of Los Angeles itself.

Disposable: America’s Contempt for the Underclass

By Sarah Jones

Avid Reader Press: 304 pages, $30

(Feb. 18)

The global pandemic resulted in so many deaths, and a huge number of those came from groups left exposed to the virus because of age, work status or physical challenges. Journalist Jones demonstrates how systemic poverty and inequality put front-line caregivers and their patients in harm’s way consistently, revealing our nation’s true attitudes toward social justice. She argues for a new way forward, but sees the sad reality clearly.

Song So Wild and Blue: A Life With the Music of Joni Mitchell

By Paul Lisicky

HarperOne: 272 pages, $28

(Feb. 25)

Lisicky, noted for his prose in both novels and memoirs, beautifully delineates how artists of different kinds influence each other by tracing his discovery of and passion for singer-songwriter Mitchell’s work. When Lisicky was a gay adolescent, that work also provided solace to him through its attention to loneliness and struggle, nearly always threaded with hope. In paying homage to his lady of the canyon, Lisicky proves that he too contains music.