Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

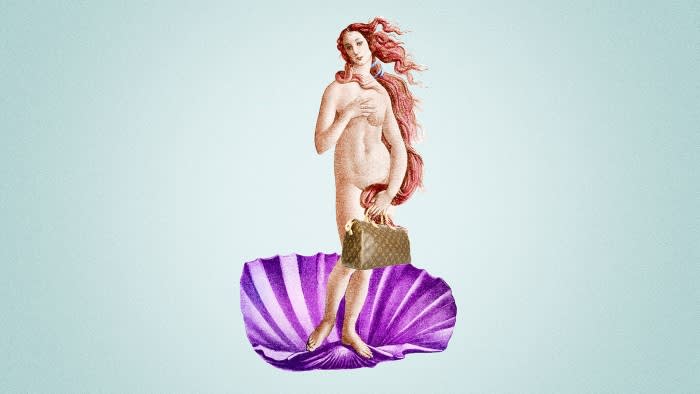

Travel broadens the mind, especially if the destination is the cradle of the Renaissance. However, the Florentine masterpiece on display that caught the attention of Harford Jr was not Ghiberti’s bronze baptistery doors, nor Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus”, but some extraordinarily expensive accessories in the window of the Louis Vuitton store. Who would pay €2,000 for a bumbag? Or €500 for a baseball cap?

My son perkily explained to me that in Sicily he could get a fake Louis Vuitton cap for €12 and he thought that was a better deal. Out of the mouths of babes. The conversation raised questions. Does the existence of the €12 fake threaten the market for the real thing? Is the customer being ripped off by the fake, or by the genuine article? And who really loses when there is a flood of counterfeits?

Much depends on what luxury brands really convey. On one view, it’s a guarantee of quality for the purchasers. Expensive brands promise quality materials and craftsmanship, and the promise is credible because the brand’s hard-won reputation is valuable. In her book, Authenticity (2022), Alice Sherwood is embarrassed to realise that she nearly wore her fake Longchamp handbag to Paris’s Musée de la Contrefaçon, the Museum of Counterfeiting. The risk of awkwardness didn’t last long, though: “Ten days after I got home, my counterfeit Longchamp fell to pieces.”

If brands certify quality, that might explain why I would pay extra for a reputable washing machine, a reputable lawyer, or a reputable condom. But it does not really seem to explain why anyone would pay €500 to ensure that a €12 baseball cap is properly stitched. Perhaps a better explanation is that buying the €500 cap demonstrates that you have money to burn.

The real trick that luxury brands have pulled off is that the two features of the brand — subtle excellence paired with conspicuous expense — reinforce each other. In its purest form, conspicuous consumption is crass and unattractive; it needs the cover story of excellence before it becomes appealing.

Both excellence and expense are part of the brand promise, then, but the difference between them matters. If the brand is mostly about excellence, the purchaser of the fake is the obvious loser: they are getting shoddy goods masquerading as something much better.

But if high-end brands are largely about expense for the sake of expense, then counterfeit brands are like counterfeit banknotes. Their ubiquity debauches the value of the once-exclusive brand and the suckers are not the people who buy the fakes, but the people who pay retail for the tarnished originals.

Should we worry? In the rich and felonious tapestry of human wrongdoing, how dastardly a crime is the counterfeiting of Prada or Armani? That depends. Counterfeits can be fatal. The most worrisome cases are not about baseball caps, but about life-or-death products such as pharmaceuticals. Or aircraft parts: in 1989, 55 people were killed when Partnair flight 394 crashed off the coast of Denmark; the accident investigators cited the failure of a component “which was of a non-standard design and of unknown origin”.

Less grave, but still vexing, are markets in which every product is junk because nobody can prove they are selling something better. The economist George Akerlof won a Nobel memorial prize for modelling such markets.

But is this inability to signal quality really a problem for luxury fashion brands? I doubt it. Those who walk into the Louis Vuitton shop down the street from Florence’s Duomo and pay €500 for a baseball cap will be confident that they are getting the real thing, and rightly so. Those who pay €12 in a Palermo street market are expecting a knock-off, and they are right too. Which brings us back to that tricky business of conspicuous consumption. If anyone can afford a knock-off, where is the snob value of the expensive original?

The economist Karen Croxson, now at the Competition and Markets Authority, once published a theory of “promotional piracy”, in which companies would tolerate the copying of some products because it created demand for the real thing. Microsoft probably benefits if tens of millions of schoolkids familiarise themselves with pirated copies of PowerPoint and Excel.

And while the possibility of counterfeit Gucci loafers seems unlikely to enhance the appeal of the real thing, maybe some brands might be happy to see influential young artists, musicians and trendsetters displaying their logos, fake or not.

Or maybe the ubiquity of the imitations builds demand for the original? Over in the Uffizi, “The Birth of Venus” is so prized because it is so recognisable, and that is down to it having been duplicated, imitated and remixed so often. Perhaps this is as true for Versace as it is for Botticelli.

Promotional piracy notwithstanding, the people most directly damaged by the existence of counterfeits are likely to be the big brands themselves. With each fake in circulation, the value of those brands ebbs away a little. The more plausible counterfeits are available, the less great fashion houses will be willing to invest in establishing themselves as the reference point for style.

That might not be a catastrophe. Does anyone think the world doesn’t spend enough money trying to make fashion brands look cool? They’ll cope. So will we.

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen