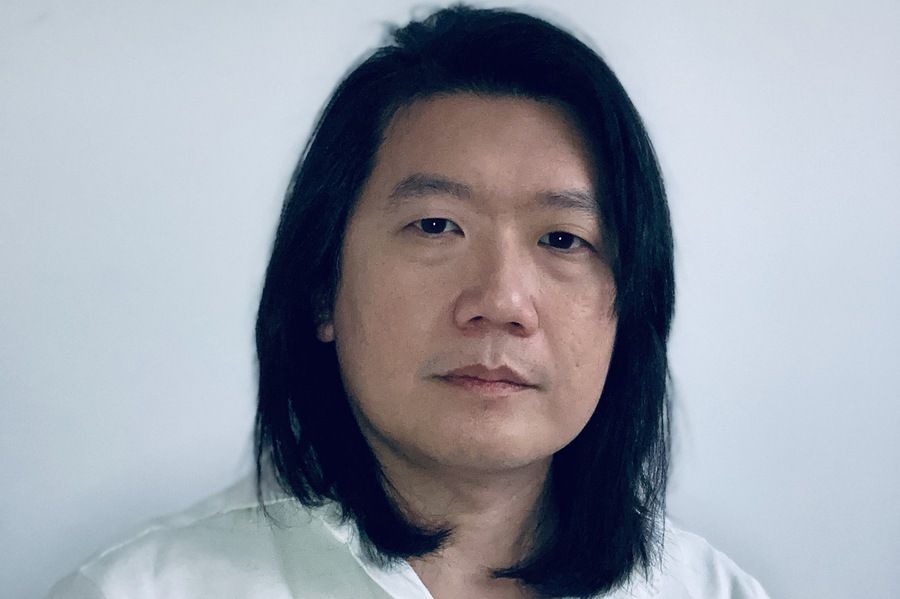

In Salesman之死 (the complete text of which appears in our Fall 2024 issue), Jeremy Tiang portrays the famous Beijing premiere of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman through the lens of the Chinese actors, and in particular the show’s interpreter, Shen HuiHui. He spoke recently about Salesman之死 with Shayok Misha Chowdhury, whose play Public Obscenities was a multilingual hit in 2023.

SHAYOK MISHA CHOWDHURY: I’m so happy to meet you; I’m so honored you asked me to chat with you about this.

JEREMY TIANG: Thank you for doing it. I was really excited when I saw Public Obscenities. I feel like there should be way more non-English plays on U.S. stages.

I feel the same way. Can you tell me a bit about how this piece came to be?

Michael Liebenluft first approached me; he had a residency at the 14th Street Y and he was bringing together a group of people with the idea of a piece about Arthur Miller’s 1983 trip to Beijing. I had read Salesman in Beijing in college, and it had always been at the back of my mind that I might do something with it one day. Michael and I had known each other for a little while, and as two of the few Mandarin-speaking theatremakers in New York, it felt like we should do something together at some point. Initially it was going to be more of a devised thing, and I was brought on as dramaturg. At the end of the workshop, I said, “Michael, this actually needs to be scripted, and I think I should write it.” He said, “Sure, let’s do that.” Six years later, here we are.

I love that. My training is as a director, and so I have a lot of fondness for those kinds of collaborations. Can you tell me more about what that collaboration was like once you actually started to write the piece?

Looking back, the piece always reflected what was preoccupying us at the moment. So in early 2017, when we first started working on this, it was much more reflective of the anxieties of the early Trump years—about immigration, what it means to move across borders, what it means to be welcome and not be welcome, who gets to move in a more friction-free way. By the end, I think I had maybe started absorbing more Covid anxiety, so just as the characters are emerging from the Cultural Revolution and learning to live their lives again, it felt a bit like I was channeling that sense of being frozen for a while during the pandemic, and what did it mean now that we were reemerging? How do we become human again?

I love that you have such specific real-life source material to push against and contend with. I am wondering how much research you found it useful to do? Did it feel as though the research you were doing was freeing up your imagination or constraining it? Or did you feel that there was a moment in which you had to leave the research behind and let the thing take flight in its own way?

My approach to research is to generate far more material than I’ll need—partly because that’s my procrastination go-to, and partly because I feel like I’m looking for the details that’ll inspire me. It’s often these bright things that I pull into the piece out of the accumulation. I don’t find it constraining, because I also find it very easy to discard the things that don’t fit. It felt in this case that we were doing a kind of counter-research, because Arthur Miller documented his own process so thoroughly, but also so completely from his own point of view. It took more digging to get the Chinese side of the story. We were very lucky that the original production was filmed for Chinese TV. It’s miraculous that you can watch the whole production.

What was your experience of watching that?

Well, I wasn’t coming into it cold, because I have seen shows at the People’s Art Theatre in Beijing, so I know that the style is slightly operatic, slightly larger-than-life. I really liked it. I watched it just in Mandarin, without reference to the English text, because I wanted to experience it on its own terms. I thought, Oh, is this going to be a little bit ’80s and isn’t going to have aged well, but it was great. I thought, you could do it today—some of it might feel slightly old-fashioned, but there was nothing embarrassing about it. It has held up really well. You can sort of see how their traditions and their long-standing way of acting have come into collision with this script from outside, with this forcefulness from Arthur Miller pushing them out of their comfort zone into a really interesting place.

One of the things I loved most about the play was what felt to me like a deliberate attention to these different theatrical vocabularies—that the languages you were contending with in the piece were not simply Mandarin and English, but the approach to performance that the different characters in the piece have. I wonder, in making a play about the making of a play, in which people were coming together with these competing approaches to performance, what performance style or vocabulary did you want to evoke in the production of your play?

We wanted to showcase these different styles to give a sense of where people were coming from. You know, Arthur Miller was going through a moment of doubt himself; the play was coming back to Broadway the following year, 35 years after it first premiered, and was it still relevant? Could you still perform it the same way? Meanwhile, the Cultural Revolution had only done propaganda theatre, so now they’re trying to go back to an earlier tradition—can they return to that? Do they need to invent something new? Our cast, and the people who participated in workshops over the years, have been largely immigrant artists, many of them coming from different traditions, with different theatrical vocabularies that all needed to be integrated. So we tried not to have the lens be American—we didn’t want the American style of acting to be the standard. Rather, what I hope is shown is that people come from all kinds of different places, and there can be meeting points. But also, there is no objectively good or bad theatre; there are just different modes of storytelling and things that people have become accustomed to.

Was this an aberration for you to work with a majority Mandarin-speaking cast?

When I was working in Singapore, of course, many people spoke Mandarin or other non-English languages. When I was first in the U.K. and the U.S., I realized, not everyone has more than one language, which is something I took for granted growing up in Singapore. That’s been a bit of an adjustment. Since then, I have been drawn to immigrant artists—to people who do have that kind of fluidity and that sense of belonging in more place than one. It’s something I would like to happen more, but it’s obviously a luxury to be in a rehearsal room where you could just speak Mandarin and most people would understand.

Can you talk a little bit more about how you and Michael worked with cast members who came into the production with different performance pedigrees and legacies and languages? And did that experience bring you back to the play and inform your writing?

Sometimes I would observe the navigations that Michael was having with the cast and be like, “Oh, that moment was interesting.” Or I’d have a realization: It’s all about tempo. The main difference they’re negotiating is that these two theatrical styles have very different tempos. When I go to China and watch a play now, I’ll think, Oh, this scene change is taking forever, because there’s no impetus to finish it quickly; it’s just going to take the time it takes. Whereas I think in the West, scene changes tend to be fast, everything has to be instantaneous. So that was an adjustment we had to make, when people were sometimes not transitioning quickly, and then we had to think, well, do we speed them up because that will feel slow to an American audience, or do we honor that actually their tempo is different?

How does this project sit in your body of work? Now that you’re on the other side of it, has it sort of propelled you in directions that you hadn’t imagined before? What was happening before it for you, and what’s happening on the other side of it?

This piece pulled together a lot of different strands of my artistic practice. I’m also a fiction writer and a translator. In fact, I spend the bulk of my time translating plays and novels, just because I translate more quickly than I write, so it’s a more reliable way to make a living. But I’d never written a play in which a translator was the central figure, so I felt like I was drawing on the part of myself that moves between languages constantly for hours every day. Putting that into Ms. Shen, the interpreter, as well as Ying Ruocheng, who translated the script in the first place, I felt like I really understood what they had been through in a way I think a lot of productions would have glossed over, because it’s seen as this invisible process, right? You’re not meant to notice it and pay attention to the people who are doing this work.

I think you foregrounded that so beautifully. What I loved is that she was sort of thrust into this role—this wasn’t who she understood herself to be professionally, so we were watching her learn how to interpret in real time, and that was teaching us how to interpret the play. I found that to be such a smart way into thinking about interpretation; watching her fumble toward it in this messy way is what made her character so compelling to me. What was it that intrigued you most about that character?

It was the realization that she is the most transformed by the experience. The Beijing People’s Art Theatre needed a reset after the Cultural Revolution, but essentially they went on making the plays that they were famous for, and Arthur Miller went back to Connecticut after this and went on being Arthur Miller. But Ms. Shen—every word passed through her, and by the end of it, she was completely different. You know, Arthur Miller has his book, and Ying Ruocheng has his autobiography, with a whole chapter devoted to this production. But Ms. Shen has been in Vancouver for decades, and her story hadn’t received as much attention until I showed up and asked, “Please, can I interview you?”

Can you tell me more about the journey of reaching out to her, and how actually meeting her fed into the writing?

Thanks to my translation work, I’m fairly well connected within China in the publishing world. I knew she had also worked in publishing, because she later translated some books into Chinese. So I was asking around, seeing if anyone knew where I could find her, and then an agent in Shanghai who I’ve worked with quite a bit messaged me back and said she lives in Vancouver. At first, Michael and I interviewed her over WeChat, a Chinese social media app; we had quite a long interview with her and I got the basic lay of the land. Then I thought, I need to go spend some time with her, so I went and spent slightly less than a week in Vancouver, hanging out with her, asking her questions, just getting a sense of what she’d been through. She remembered it so clearly, and provided all kinds of details that found their way into the play, with viewpoints that sometimes showed how Arthur Miller’s sense of what happened in the rehearsal room wasn’t necessarily what was happening, because of course, he didn’t speak the language and not everything was translated for him.

What was your relationship to Death of a Salesman before this project? And how do you feel about it now?

My first encounter with the play was very similar to the characters in my play. I read it as a teenager in Singapore in the ’90s, just before the internet, so I couldn’t look up any of it. There were huge chunks of it where I had no idea what exactly was happening—aspects of suburban American life I had no clue about. I came to it with the awareness that it was considered a canonical play, but also feeling very removed from it, and feeling very confused about what kind of reaction I was meant to have. Singapore only became independent in 1965, and in the early ’90s, there wasn’t as much of a literary or theatre culture as there is today. So here was this play I didn’t really understand, and there were plays in Singapore that felt more familiar but seemed to lack the technical facility I could see in Arthur Miller’s work. I was trying to put all of these pieces together and figure out where I fit in. Now that I live in New York and work in theatre, I think I have a relationship to Death of a Salesman that probably is more similar to the average American’s relationship. But my first encounter with it still lingers—that is, the slightly alienating effect that maybe I was also trying to work through in writing this play.

I found it quite poignant how these characters’ interpretation of Death of a Salesman at first reveals these cultural dissonances, the frictions or misunderstandings, but then as they start to understand the play, they collapse the play into this soundbite—that capitalism is a lie—which is also a really rich understanding of the play.

Yes, or that moment where they go, “Oh, it’s a play about parents’ aspirations for the children. It’s an Asian play.”

On the question of acting style, I also loved the beautiful moment when we watch the scene from the more traditional production that they were doing when Miller was in town, and then seeing them wrestle with the value judgment around whether or not that’s a worse kind of acting. But then seeing in the footage of the original production, in Linda’s final line, that there is actually a kind of pathos that performance style brings to the play that cracks it open in ways that we might not expect.

I think the expressiveness that could be seen as exaggerated or caricatured also makes them available to a kind of emotional sincerity. I was also inspired by this kind of cultural crisis that happened in China. That production of Thunderstorms that Arthur Miller saw has remained in the Beijing People’s Art Theatre repertory for decades; it’s considered one of their foundational works. A few years ago, they revived it again, but some young people in the audience started laughing at the more melodramatic bits. There was this firestorm online and in various forums where people were going, Does this mean we’ve lost touch with our own culture? Can young people not appreciate this? Do these productions have to evolve, and can we preserve them? That’s something that they had to navigate, just as they had to navigate it with Arthur Miller.

Have you thought about bringing the play to China? How do you imagine it would be perceived there?

We’re exploring the option. Opinions vary as to whether we will even get past the censors, for one thing. I would definitely love to bring it to Singapore, where I think audiences who are also between cultures would appreciate it. If we could bring it to China, I think it would be received as an outside view of China.

What audience responses did you get when the show ran in New York? Anything that surprised you?

I definitely hoped for large numbers of Chinese-speaking audience members, and there were some people who didn’t speak English, so I’m very glad I made that decision to insist on the whole thing being supertitled. Then we went viral on Chinese social media, which I hadn’t thought would happen, and the audience changed; we had many more university students from China and young professionals working in New York, who may have been to the theatre before but weren’t habitual theatregoers, and who came to this because they felt it would speak to them in a way that maybe an American play wouldn’t. My producers later said that you could tell the exact moment we went viral and it became a more Chinese-speaking audience, because our bar sales fell off a cliff.

Amazing. Tell me, what are you working on now? What are you excited to write next?

I write very slowly—I was gonna say, to my agent’s distress, but actually she’s cool with it. I’m excited to translate more plays. I’ve been finding all of these really interesting, experimental, daring plays, a lot of them from Taiwan, which has a separate theatrical culture to China, and translating them and trying to bring them into the world.

That’s so exciting. There are so many plays out there, contemporary and otherwise, that we’ve literally never heard of here in the American theatre. The more we have multilingual playwrights working in America, my hope is that some of those plays can show up here.

I would really love to see that happen. I knock on doors, I harangue literary managers: Please program this, don’t commission yet another version of Chekhov.