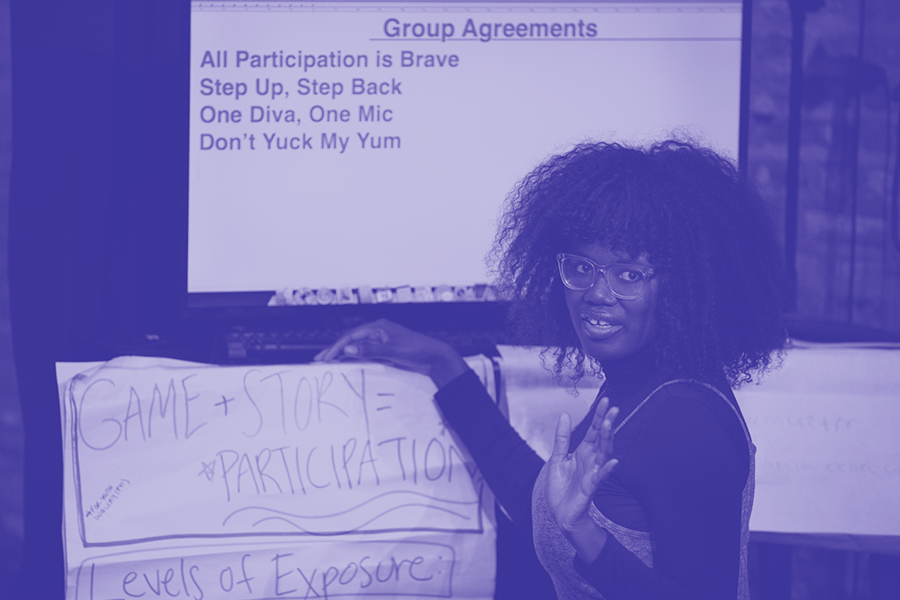

Dionne Addai, education manager for About Face Theatre. (Photo by T.G. Samuel of Starbelly Studios)

Though her career as a box office manager began more than three decades ago, Ruthie Rodriguez still remembers her debut run at Houston’s Alley Theatre like it was yesterday.

“We did Jekyll & Hyde my first year, and the demand for tickets was pure chaos,” she recalled. But, giving some indication of why she’s still in the field— she’s now at Houston’s Theatre Under the Stars (TUTS)—Rodriguez quickly added, “I loved every moment of it.”

Empathy is Rodriguez’s superpower, whether she’s resolving ticketing issues, comforting parents with restless children, or navigating high-demand musicals. “It’s not exactly what you say to people, it’s how you make them feel,” she explained. “Customer service is not easy, and when people are spending their hard-earned money on you, and they could choose any place, you want them to feel like they’ve made the right choice.”

For 32 years, Rodriguez was a fixture at the Tony-winning Alley, the oldest theatre company in Texas and one of the oldest in the U.S. During the pandemic hiatus, she worked virtually as an assistant to Broadway director Michael Wilson; now she lends her expertise to TUTS. Beyond her front-of-house role, Rodriguez has always been active in the local scene, and currently serves on the boards of On the Verge Theatre and Lionwoman Productions TX.

Born and raised in Houston, Rodriguez grew up in a family where musical theatre was an honorary member of the household. As the youngest of five, she was introduced by her older sisters to ballet and to classic films. “My mother loved the music from South Pacific, and she would sing it to me before I’d go to sleep at night,” she recalled. Some of her personal favorites include Singin’ in the Rain and Sweeney Todd.

After graduating from a performing arts high school, Rodriguez naturally pursued liberal arts and theatre at the University of Houston-Downtown. With a four-octave range, she dreamed of being an opera singer, but her plans pivoted when she met the late Bettye Gardner, an icon of Houston’s theatre scene and the former head of the Merry-Go-Round School Theatre at the Alley.

“Everyone wanted to know her,” Rodriguez said. “Bettye had asked me if I would come in and do some backstage work, and I did. Then someone there asked me if I was interested in working in the box office. I said yes, and that’s how it all began.”

Challenges during a stint in Australia with a tour of The Book of Mormon earlier in Cessalee Smith-Stovall’s career catalyzed her commitment to diversity; she now serves as deputy managing director director and director of belonging and inclusion at Seattle Children’s Theatre (SCT). She was one of a number of Black American performers who traveled Down Under to play the show’s Ugandan ensemble, along with two white performers who played Elder Price and Elder Cunningham.

“There was this big fervor about the two white actors being brought to Australia, but those of us who came as Black African American performers didn’t get that same energy from the community there,” Smith-Stovall recalled. Most audiences seemed to assume that the reason for bringing the Black American actors were brought over was only because, as she put it, “of course they had to bring in actors to play those roles, because they don’t have Black actors in Australia.”

Smith-Stovall’s personal passion for performing began in the fourth grade with a teacher who told her mom that she “talked too much in class and that I needed an outlet for my energy,” she recalled. “My mom didn’t really know what that meant, so she put me in drama class, and there I stayed for the next 30-plus years.”

From that moment on, Smith-Stovall immersed herself in high school plays, dance classes, church choir, even cabaret theatre. At Florida State University, she studied music and theatre, later performing in regional theatres, theme parks, and on cruise ships. But after Smith-Stovall noticed the huge difference in the reception of Black American performers in Australia, she began to ask more critical questions in her workplace.

That was a decade ago. Now, in her role at SCT, she said her most cherished experiences there involve watching performances with her daughter. It’s not just fun—she said she also gains invaluable feedback from young audiences that she can apply to future productions. “Kids are really honest,” Smith-Stovall said. “They talk back to you in the moment; they let you know what they believe and what they don’t believe.”

No matter what position she holds, Smith-Stovall’s commitment to inclusion will always be a driving force. “It’s important that DEI sits at the core of the people,” she said, “not the job of a person.”

Two days into her job at Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, Deb Hildebrand found herself at home with an anxious, nearly bald parrot named Toots. The alarm system for the Playhouse’s Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre was being tested, so Toots—on hand for a production of Tina Howe’s Painting Churches—couldn’t stay alone overnight. Hildebrand, as the Shelterhouse properties and run crew chief, was tasked with the bird’s care.

“They got him really cheap from a pet store,” she recalled, “and because it was a nervous parrot and kept plucking all of its feathers out, the pet store didn’t think he was going to live. Toots ended up going home with a colleague and lived over 20 years.”

Indeed, Hildebrand’s nearly four-decade career at Cincinnati Playhouse is filled with animal antics. She recalled that every time a scarlet macaw got handed through a trapdoor during their run of Treasure Island, the bird would “poop on the person handing them up. She ate better than I did. She liked scrambled eggs for breakfast every day.”

There was also a goat that needed daily walking, but “you had to walk him away from the cars, because if the cars were under trees, he would jump on the cars and eat the trees.” Hildebrand found a home for the dog that she fostered for The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. “If they needed homes, we found homes for them,” she said. “I really like that part.”

Hildebrand’s love for animals is evident in every facet of her life. Whether volunteering at the Cincinnati Zoo or caring for a dog and three cats at home, animals have been her constant companions. In fact, a job in the theatre wasn’t even part of her original life plan; she attended Miami University hoping to become an animal behaviorist.

“But my biology teacher was insane, and so I took a theatre class and never left,” she said with a laugh. “My father graduated from Kent State as a scenic artist and actor, and he ended up a microbiologist, so we just switched roles.”

After graduation, a recommendation from her technical director landed her a newly created position at the Shelterhouse, and she’s been there ever since.

“I’m the only one to do this role here,” she said, with a hint of pride in her voice. “Your job is never the same, and that’s the best part.”

Boutayna Chokrane (she/her) is a Chicago-based journalist, covering music, the arts, and all things culture.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.

Related