Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

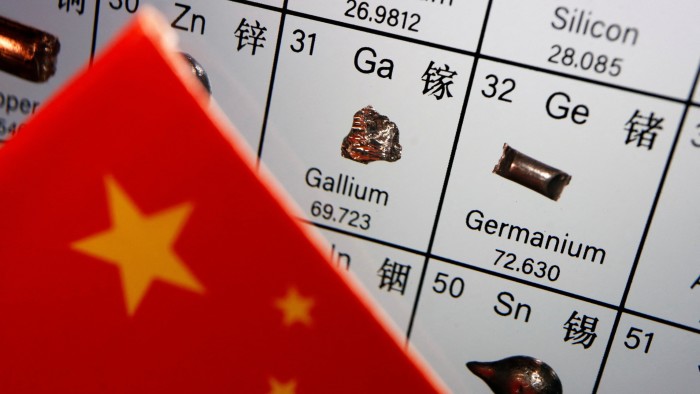

Destructive as it may be, there is a certain symmetry to the latest round of tit-for-tat trade wars. Washington is clamping down further on exports of tools and tech required for cutting-edge semiconductors to China; in response, Beijing is withholding critical minerals and metals used in many of the selfsame military and tech applications.

This has long been a lever Beijing can pull. China produces 98 per cent of the world’s supply of gallium and 60 per cent of germanium, according to the US Geological Survey. It dominates a host of other so-called rare earth minerals — they are not so much rare as a hassle to extract — used in everything from F-35 fighter jets to night goggles to electric vehicles.

Beijing’s ban, reckon researchers at the USGS, could shave £3.4bn off economic output. That is hardly enough to set Americans quaking; the country generates that in an hour or so; even the modelled worst-case is $9bn. But it may also understate the case. Unlike China, which has accelerated a self-sufficiency drive on chips, corporate America has done little to wean itself off China’s critical minerals.

China’s no-holds-barred push into the likes of gallium made it financially unviable for bit players to compete. Switching on or adding capacity in mothballed plants in places such as Kazakhstan, Hungary and Germany will not be immediate.

Take-off is proving slow in the US too, even when it comes to releasing gallium — a byproduct — from existing bauxite or zinc smelters. Nyrstar, owned by commodities trading group Trafigura, has yet to progress on a zinc smelter plant in Tennessee, which it reckons could fill 80 per cent of annual US demand for gallium and germanium.

One answer is more state help or making it more accessible — with a pathway to top-ups if, as is inevitably the case, costs overrun. Australia’s (putative) pioneering rare earth refinery is only just back on the cards after Canberra this month ended a year of wrangling by approving an additional A$400mn of funds, plus potential top-up. The initial A$1.25bn was agreed in 2022.

An embargo may of course reverse these dynamics, pushing up prices and making the business more profitable: the end-of-year spike is illustrative. Gallium is a byproduct of other processes; plugging in some extra circuitry to capture it without polluting the environment makes sense if prices are higher. This is what Rio Tinto has dubbed “nose to tail mining”.

But as the Nyrstar and Australian experiences show, none of this happens quickly — and gallium usage is rising. GaN-based semiconductors are faster and more efficient than their silicon peers. Germany’s Infineon recently developed 300mm GaN wafers and sees the GaN market growing to “several billion dollars” by the end of the decade.

It is perfectly possible for the US to find other sources, by bolting on extra piping to relevant smelters, investing in overseas producers or both. But it needs to move fast.

louise.lucas@ft.com