In the latest episode of “The Envelope” video podcast, director Coralie Fargeat explains how she prepared star Demi Moore to film “The Substance” and “The Brutalist” filmmaker Brady Corbet discusses his desire to make films that viewers can never quite pin down.

Kelvin Washington: Hello and welcome to another episode of “The Envelope,” Kelvin Washington alongside the usual suspects. We have Yvonne Villarreal, Mark Olsen. Happy to be here with you, as always. I’m going to start with you, Yvonne, Coralie Fargeat for “The Substance.”

Yvonne Villarreal: I want to start with you and this tie. I didn’t notice it until now. Look at you.

Washington: Listen, It’s just the little things. I’m glad you noticed that. You’re getting me a little emotional here. You know what? But I appreciate you noticing that that means a lot to me. And I’m trying to just maintain my professionalism.

Villarreal: Why? Tell me, what’s the story?

Washington: I needed a pop [of color] at some point, so I went with a tie I haven’t worn in like a year and a half to a couple of years. So I said, “You know what? Bring that one on out.”

Villarreal Oh! When you said it was going to make you emotional —

Washington: You made me emotional because I’m ready to talk movies and you made me talk a little fashion. Listen, you’re actually going to have a dark-skinned brother turning purple, blushing up in here. Let’s get to “The Substance.”

Villarreal: Well, appearance is everything, as we learn with “The Substance.”

Washington: That was smooth.

Villarreal: I try. So “The Substance” is a dark satire slash body horror. It’s up for five nominations and it follows this, you know, actress turned fitness guru who’s sort of past her prime, played by Demi Moore. And she’s taken to this underground drug known as The Substance, to sort of reclaim her youth. And it creates this younger, more perfect version of herself. And that version is played by Margaret Qualley. And throughout the course of the film, it’s this battle of control over their lives: Do I want to stay who I am or do I want this perfect version? And it really is sort of a commentary on the violence that we inflict on ourselves. It was a poignant discussion with Coralie. I really enjoyed it.

Washington: We can all relate to that a little bit, especially with social media and how we view ourselves or present ourselves.

Swing over to you, Mark. You have Brady Corbet and “The Brutalist.”

Mark Olsen: That’s right. Brady Corbet is really interesting. He was an actor as a teenager. Transitioned to filmmaking. This is his third feature film as a director. And, you know, barely six months ago, “The Brutalist” premiered at the Venice International Film Festival. Didn’t have a U.S. distributor. Really caused a sensation there. He won the best director prize, was picked up by the studio A24. They’ve put together this campaign and launched the film. It’s now got 10 Academy Award nominations. It’s just an amazing trajectory. And it’s the story of a Hungarian immigrant, an architect played by Adrien Brody, who comes to America after World War II and what he encounters and just trying to practice his art, to find his way. And it’s this just really dense, rich story about the immigrant experience, about ambition, about sort of artistic triumph and failure. And Brady speaks about the movie with such passion and conviction, it’s really an exciting conversation, I think.

Washington: And it’s just such a large scale film, too. We’ll see how it does. All right, here is Yvonne with Coralie Fargeat of “The Substance.”

A scene from “The Substance.”

(Christine Tamalet / Universal Pictures)

Villarreal: Coralie, thanks so much for joining me today. Congratulations on the film’s five Oscar nominations. “The Substance” has themes that have been with you for a long time, but it arrives in a growing celebrity-worshipping culture, one where there’s Ozempic and Botox obsession. What does that say to you about these themes that just never seem to go away?

Fargeat: Exactly that. I think it’s a different product but same story. And unfortunately, I think everything you’re speaking about really shows how much those issues are still very much there and the pressure of conforming to a certain ideal still tyrannizes us, in a way. For me, the movie is really about wanting to say that I’d [like for us to be] freed from this jail, to find our real freedom of doing what we want. The idea of the movie is not to say you shouldn’t do this or you shouldn’t do that, but you should do whatever you want for yourself, just because you want it. I still think that there is still so much external pressure that’s made us think that we have no choice but [to change] ourselves to be acceptable or to be interesting. To me, that’s the real issue. So the movie was really about trying to make a big kick in that system, to say, “Let us be who we are and look at us for who we are,” not the fantasized version that has been shaped [over] 2,000 years.

Villarreal: Was there a moment or an experience that incited this idea for you? Was it something someone told you? Was it an inner thought you felt about yourself that led you to this project?

Fargeat: It was definitely an inner thought. When I had passed my 40s, I really started to have these crazy, violent thoughts that my life was going to be over — it’s the end of being interesting, it’s the end of having any value in society. The way this [thought] was so strong and hit me with so much violence, I questioned myself about how crazy this is. Hopefully I’m not at the middle of my life and already thinking that I’m done, that it’s over. It really made me realize that if I wasn’t doing something with that, it could destroy me. It’s a theme that lives with me since [ I was] a little girl because the movie is not about just aging; it’s about how you’re supposed to look and behave to conform to the idea that society has built of what it is to be a girl, what it is to be a woman. And a huge part of it has been, I think, defined through the eyes of men — what a girl should be, what a woman should be, to be interesting in the eyes of men, to be desirable, to be worshipped. At different stages of my life, it has brought huge issues about feeling that if I wasn’t in those boxes, I wasn’t worth being in the world. So at each stage of my life, it kind of tyrannized me: “If I don’t look like that, I should look like that,” if I wanted to be someone [who] could be interesting.

Villarreal: I know being 5 and playing with Barbies, I have vivid memories of being fixated on the waist of the Barbie, thinking, “That just doesn’t seem real.” As I got older, I was like, “I need to be like Kimberly, the Pink Power Ranger.” What do you remember about the earliest memories of that for you, of measuring yourself up to what’s out there?

Fargeat: There was the Barbies, of course. There was also the fairy tales — Cinderella [was a] blond, thin, beautiful girl with this beautiful dress. And school, I remember, shaped a very precise idea of who was the beautiful girl and who wasn’t. When I was a kid, I remember, I had short, frizzy hair with glasses. And I wasn’t at all like the model that was supposed to be those Barbies. It’s funny because I remember this now, some guys were calling me monster. Everything infused in a way that if you’re out of the boxes of the representations that society creates for people, it brings a lot of violence. I think in our generations, it was a very one-way of defining who was worth being called beautiful and who was worth being called interesting. And a bit later on, it was all those babydoll Lolita symbols that kept shaping this kind of Barbie ideal that we grew up with.

Villarreal: Do you find yourself talking about these things a lot with your girlfriends?

Fargeat: Not so much. I do believe that it’s still something that is very taboo and that many women deal [with by] themselves. Maybe we think about it, but we don’t share it. I think there is still a massive fear of, if we speak about that, we’re going to be sidelined, because it’s always easier to be with the norm. It’s always easier to be with what is the most popular. And so that’s also the idea of the movie. I think there is so much that’s going on inside us internally that we are used to just keeping to ourselves. And we go in society, and we smile even when something makes us uncomfortable. The number of times [I’ve been told] comments, and you just smile because that’s the way you’ve been used to dealing with things [when] you don’t want to make a problem, you don’t want to be the one that’s going to be spotted. I think it’s a huge part of the human story that we don’t hear, that we don’t look at that, we don’t listen. And the idea of the film was to say, “Look at that! Look at what we really go through. Look at who we really are and look at our stories. Look at our inner fights, look at our complexity.” And I wanted to make it, all that, explode in the face of society.

Villarreal: To that point, much like your first feature-length film, “Revenge,” “The Substance” is a very visceral and sensorial experience. The sounds that we hear, the shots and the framing of the shots and just the colors — there’s a lot to take in, and you feel it as you’re watching it. I’m curious what preproduction is like for you. Are you just listening to a bunch of sounds — like, “What do I want the shrimp to sound like as Dennis Quaid is munching?” Walk me through the process for you.

Fargeat: I start not with writing dialogue but really through visuals, sounds and the visceral experience that you’re going to feel. All these combined together create a real experience that you enter and that you feel. So, before I start writing, or while I’m writing, yes, I’m listening to a lot of music, to a lot of sounds, to find the identity, the vibe that I want to convey.

I remember for this one, I listened to a lot of experimental music, to a lot of music that [was pulsing], almost as if it were coming from inside a body as a heartbeat. And this started to shape the kind of general sound identity that was really going to define the experience. And when I found pieces that I loved and that really inspired me, I started to write my scenes, listening to them. So they really kind of shape the rhythm while I’m writing … And it’s the same for the visual and the colors. I research a lot of images. I build a very, very detailed, what I call a “look book,” which is visuals that start to create the identity of the film before I start to work with my heads of departments. So, it goes from paintings to photographs that’s going to give a vibe, that’s going to give something that you feel, that starts to shape the specific identity of the film.

Villarreal: Is there a source of inspiration that would surprise us, either sound-wise or visual-wise?

Fargeat: No, it’s things that I gather [over] a long time because, when I see something that I like, I take a picture and I keep it somewhere, or when I hear music that I like, same thing; I research it and I put it somewhere. And so I love to collect things that create a spark, a creative response in me, because it means that there is something that resonates and then that can feed my own inspiration. What I also love is I don’t [limit] myself; [I] take inspiration in everything — in classical paintings, let’s say, or in pop culture, modern images. I don’t have any rules.

Villarreal: There were so many moments in the film where I just wrote, “I want to see how this is written in the script.” I want to talk about the birth sequence in particular. It’s such an arresting display of body horror and filmmaking magic. How did the idea of another human birthing out of Elisabeth come to you and what were those conversations like to achieve a moment like that for the screen?

Fargeat: It’s very interesting that you focus on that scene because, in fact, it’s the very first scene that I wrote even before I knew who my character was going to be. I think that scene is really defining the DNA of the whole film. It has the relationship with the body, with the nudity, with “What is your body for real?” when you look at it in the mirror, when it’s heavy lying down on the floor. Also, what you can feel inside of you as a growing experience that you don’t see but that can be very visceral. This scene has no dialogue at all. The only dialogue is when Sue is finally born and looks at herself in the mirror and says, “Hello.” … Also, this scene creates a very experimental relationship to the filmmaking with the POV relationship, where you literally wake up in someone else’s body as if you are experiencing yourself the discovery of, “OK, I’m not in my body anymore. I see the other body on the floor. What am I going to discover?” And you discover yourself in the mirror with this fantastic new appearance.

That scene was the first idea. In fact, it was the first idea that sparked “The Substance,” having literally this fantasy of having a better version of yourself. The fantasy that we have: “If I were like that, it would solve all my problems; I would be happy;.” To literally take shape for real, to literally happen for real. It was the key scene that took us most of the time in prep and in shooting to achieve because it was a very technical scene to feel seamless, to feel that everything flows, to feel that everything is in one sequence shot, but, in fact, there are so many technical challenges that we had to face. For instance, when you are in a POV shot and you want to look at yourself in a mirror, how you do that? Because you’re going to see a camera. We ended up building a second bathroom. It’s not a mirror that you see, it’s an empty hole. In the first bathroom, there is the camera that’s filming the POV of Sue. And Margaret is in the other bathroom and she synchronized her movements with the camera. So all this is defining what we are going to film with the mirror, which shots and how many fake backs we would need to shoot all the deformation, the back opening, the arm coming out. So everything was very precisely storyboarded. And it was one of the scenes that I had in my head in the most detailed way. I knew exactly what I wanted to film. And if you don’t see the leg of Elisabeth in your shot, you don’t build that part in prosthetics, because building prosthetics is so expensive that we need to measure and manage the constraints of that.

Villarreal: You talk about it being so detailed in your head — when you’re writing it, are you writing it in French or in English? Or both?

Fargeat: Both. Basically, the way I work, I really let what comes to the page come. Some things come in English. Most of the dialogue comes in English, some of the descriptions as well. But when it becomes more elaborate — because I write a lot of description — [that] most of the time comes in French in a very elaborate way, which I love. And so when it comes in French, I let it come in French and then I work with a translator to translate it into English. But at the beginning, it’s really what we call Franglais.

Villarreal: We need to talk about Demi Moore. What were those conversations like of both pitching this project to her but also letting her really have a sense of what you were going to be asking of her in this performance?

Fargeat: When I was writing, I knew that the casting process was going to be very challenging because I really wanted — to best symbolize my story — to be able to work with what you call a “star,” representing herself. But I knew that it was basically going to confront an actress [with] probably her worst fear. So I knew I was going to have a lot of “No’s” in the process, which happen. And the name of Demi arrived in the conversation, and I said, “Wow, that’s a great idea, but let’s not lose too much time with that, because I’m sure she will never want to do something like that.” I had this image of her extremely in control of her image or appearance, and I said, “I don’t think it’s realistic to think she’s going to do that.” But I said, “Let’s send the script. We’ll see. But let’s not wait too long.” And it turns out that she clicked instantly with the script; she really had a very strong reaction. We met in Paris. And for me, the most important thing was, as you say, to explain to her extremely precisely what the film was going to be. Because I knew that the movie is really a vision that expresses itself in the certain way, that makes the whole building work. And if you change something, it unbalances everything. Things are taking shape to kind of explode on the way. I knew she had never been in such a genre film. I wanted her to have all the elements with her to be sure that we wanted to jump into the same boat. So I took a lot of time discussing with her, not so much about the story, because I think it was the thing that was crystal clear for us that we both had lived in our lives in different ways. [It] didn’t need further explanation. It was something that truly resonated for both of us.

But I spent a lot of time discussing with her everything else — the visual world of the film. I shared with her a lot of visuals, a lot of references, a lot of sounds. Discussing with her also all the technical challenges that were going to come into account in the shooting, because those define the way you’re going to shoot. And for her, of course, what she’s going to have to deal with performance-wise, because also I work in a totally untraditional way. I don’t do like a master and then I do a close-up. I really build my filmmaking in a very specific way of focusing on the shots that are the most important and that I need to spend the most time with. And so it can be sometimes unsettling because it’s a little bit of a different process … We also, of course, discussed the prosthetics — the fact that it was going to imply so many long hours in the chair; it was going to imply a lot of constraints on the schedule; that we’d have to shoot maybe [out of] continuity; to work depending on what prosthetic needs. And, of course, we discussed the nudity, because, for me, the nudity was a real tool of telling the story. The nudity has a real meaning, and it has a meaning when it’s with Elisabeth, and it has a another meaning when it’s with Sue. And I wanted to explain each shot that I wanted to film and to explain what was the meaning of each shot.

In parallel, I also read her book, her autobiography. And I really discovered another side of her that I didn’t know at all. That she had been taking many risks in her life. She had been thinking out of the box. She had done many avant-garde, provocative choices ahead of her time. And all this made me understand that, “OK, I think Demi has what it takes to go into the risk that this story needs.”

Villarreal: I’m curious about the prosthetic part of it, in particular, for both Demi and Margaret. They are in hair and makeup and doing the prosthetics for six hours, and then they’re on set — maybe they can’t hear because of it, it could be restrictive, it could be frustrating, I imagine. What did that require of you, in terms of connecting with them and figuring out how to direct them in these moments where it maybe required a little bit more finesse?

Fargeat: It was a very key aspect of the process. One interesting thing about that is you can’t know in advance how someone is going to react to the prosthetics. That’s the first thing the prosthetic artist told me. He told me, “They can be willing to do it and super happy to do it, but until they have the prosthetic on their face, you don’t know how they’re going to react.” And that’s exactly what happened. For instance, I know that Demi, she loved working with a prosthetic. It was something that was building her character. So the seven, eight hours in the chair was almost as if it was her prep time as an actor, to literally start to build her character in many different stages. Also because when you have six hours in makeup, then you just have two to three hours to actually do the scene. It’s very challenging because you have to find your character for the first time because you can’t rehearse with prosthetics. It’s so expensive that the day you apply it, you have to shoot with it and then it’s destroyed. If you shoot another day, you have to build a prosthetic all over again. And so it was scary. I know that for both Demi and I, for those big moments when it’s so impressive, you have little time so you know that you can’t miss. It’s stressful. But I think it brings something that goes out of you that you have to do.

And for Margaret, it was very different because it turned out that — and we didn’t know, she didn’t know, I didn’t know — she really didn’t like at all the prosthetic for her. It was very almost claustrophobic. It was working in a bit different way. First of all, trying to limit everything we had to have with Margaret in prosthetics and also do things that we could do with the body doubles. I loved also the fact that even if she hated the prosthetic, there is this actor instinct when she felt that her performance was in danger or was not as good as what she could do, even if she hated it, she wanted to do another take. This is, to me, the beauty of the commitment to performance, when she was in the monster. And it’s the moment where people push her to the floor and she falls down and she cries saying, “It’s me! It’s me! It’s still me!” I remember [with that] scene, she was tired and at some point I said, “OK, let’s do a last one. And I think it’s OK.” And after we did the last one, she wanted to do another one because she felt it was such an important moment, it was such an emotional moment. The performance was the most important. And she stayed committed to that. And I think that’s the beauty of actors, that they are committed to their parts.

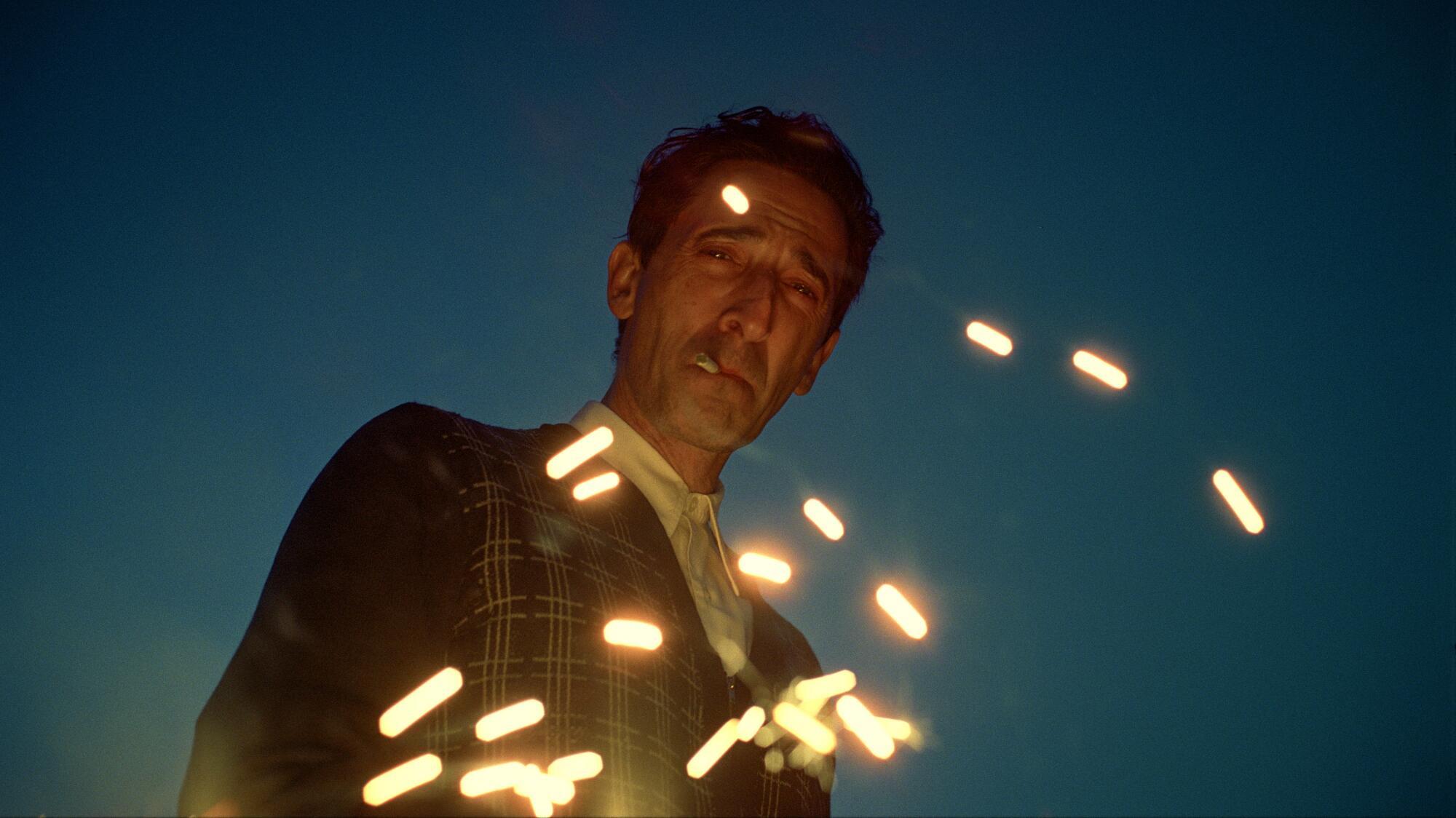

Adrien Brody in “The Brutalist.”

(A24)

Mark Olsen: As we’re having this conversation, it’s February 2025. Barely six months ago, the film premiered at the Venice International Film Festival without a U.S. distributor. And now, here we are. It’s nominated for 10 Academy Awards. What has this period of time been like for you?

Brady Corbet: It’s mostly been exhausting. But I think that what I’m looking forward to is having some time to catch my breath and reflect on all this. It was such a marathon. Every part of the process was a marathon. Shooting the film is a marathon, the postproduction process was a marathon, for a variety of technical reasons. Also, because of the length of the film — the film takes up so much space that everything was a conflict in terms of how much time we had originally planned for the mix, how much time we had planned initially for the grade. And because you’re essentially grading and mixing two movies, not one, of course, that’s a very different sort of metric. And so it was complicated. And then also just the stress of getting the prints to Venice on time and through customs. It was just a lot. And so it’s been a really long, long run, and I’m looking forward to having a bit of normalcy again and some time with my daughter.

Olsen: Considering the movie did take seven years to make, have these last few months felt a part of that continuum, or was it almost like there was a reset and this is some whole new experience?

Corbet: It feels like the same thing. And that’s what I mean. I think that because it was this continuum, I haven’t had the the chance to really have the perspective to appreciate it. I mean, there’ve been a couple of moments, especially at the Golden Globes when I was there with my 10-year-old girl, that was incredibly moving. And to be able to share that has been amazing. But I’m mostly on the road, I’m mostly on the road on my own. And so it’s a gauntlet.

Olsen: It is wild to me that while you’ve been finishing “The Brutalist,” promoting “The Brutalist,” you and Mona Fastvold, your partner in life and filmmaking, have a whole other movie that you’ve also been working on, a musical about the Shakers. How is that even possible?

Corbet: I left that part out. It’s true. We shot a film this summer that was very, very challenging for a variety of reasons. It’s all set in the 18th century, there’s hundreds of dancers in most scenes and sequences in the film. It happened to be the hottest summer on record in Hungary, where we were shooting. So it was north of 38 degrees Celsius or something. So it was in the 90s and 100s for the whole shoot. And the dancers, because they were cloaked in so much fabric and stuff, it was just really, really brutal. I was shooting second unit during the day for Mona and producing the film for her along with our partners. And then I would go home at night, and I’d work on post remotely on “The Brutalist.” And then sometimes I would travel to either London or Paris for a final mix day or 70-millimeter test, which were done at the Cinémathèque Française. And it’s just been pretty full-on.

Olsen: Tell me more about your collaborations with Mona. When the two of you are writing a project, do you know from the start which one of you is going to be directing that project? How does that process work?

Corbet: Yes, definitely, when we’re writing something, we’re writing something for her or writing something for me. We also write for other people too. Which is an interesting thing. We like working for other people. Of course, the two of us know each other so well that it’s easy for us to anticipate what the other one is maybe chasing after, and so we’re not very dogmatic about it. Sometimes we write together. I usually work at night, and she’s a very early riser. So sometimes I’ll just leave something on the table for her, and then she’ll look at it over breakfast. So it’s pretty loose.

Long before we had a child together or anything, we were friends for years and we worked together. So I think that if we had become a couple and then started to try to work together, the dynamic would be different. But because we worked together first, we’ve always sort of reverted back to that same way of functioning. And writing is an improvisational process. Essentially, you have a pretty good sense of a beginning, a middle and an end at the beginning of that process. But so much of the sort of sinew or the connective tissue between scenes and sequences comes from a process of yes and, yes and, yes and, which is the first rule of improv. You never shut anyone’s idea down. You just are constantly taking it in different directions. And then I think that there’s maybe a more important part of the process, or the most important part of the process, which is really just talking about a project in terms of its philosophy. What is it really about? Something I struggle with a lot is that there are a lot of contemporary films, and novels as well, to a certain extent, that for me, I just sort of know what they are in the first five to 10 minutes and they continue to be that until the credits roll. And they might be well made, but they don’t really transcend for me as a viewer. And I need films to be about a lot. And because they’re so difficult to make anyway you slice it, even if you’re making lighthearted fare that is for the teenage demographic or whatever, people are still suffering to bring that work to life. And so I think it’s so difficult no matter what that you might as well — it really should be for something.

Olsen: You’ve been open about the fact that “The Brutalist” in part was inspired by the experience of making your previous film, “Vox Lux,” and the idea of an architect also being someone who has to marshal a lot of money, a lot of people, just a lot of forces, to create their work. They’re not just painting in a garret on their own. Can you talk a little bit about how to you the movie is in some way an allegory of filmmaking?

Corbet: Just for clarity’s sake, the film is obviously first and foremost about postwar psychology and postwar architecture, the way in which those two things are intrinsically linked. It’s about a post-traumatic generation, which every film I’ve made is sort of chronicling. “The Childhood of a Leader” was about the interwar period between the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and the Second World War. With “Vox,” it was a film about post-Columbine, post-9/11 America and how America has metabolized that. And this film is about the 1950s, which is an era that the conservative agenda in this country especially really romanticizes. It’s a time that a lot of folks seem to want to get back to. And so I wanted to really investigate that. Of course, as soon as I started working on a film about an architect, it was easy for me to relate to what his or her circumstances might be. So we imbued it with direct quotes from our own life and experiences. And there are a lot of Easter eggs in the film for the people that they’re intended for.

Olsen: Like what?

Corbet: They know. But I think that no matter what you work on, it ends up, of course, being personal at some point. Even “Vox” was a film that I felt really personally connected to because I watched a lot of people, as a young man, become public figures at a young age. I myself became something of a public figure at a young age and didn’t love it. I resisted it. And so I empathize a lot with this character, who is admittedly abrasive, but I still empathize with her. So I think that Mona and I with this, because the film is also about a relationship, we wanted it to feel like something that we recognized in a relationship — which was to take the tropes of the 1950s melodrama and subvert them a little bit. And so they’re constantly sort of insulting each other, and the relationship is not what you expect after anticipating Felicity’s character’s arrival. And I like that. I was thinking about relationships between Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and this kind of the dynamic between an intellectual couple of a certain era.

Olsen: The film has a certain scale and ambition to it, a scope. You’re shooting in this somewhat outmoded format of VistaVision. You have a limited budget, a limited number of days. Why do you think you make it so hard on yourself?

Corbet: Because I just don’t think [it] would be very good otherwise. I think it’s so difficult no matter how you slice it, that you might as well be fighting for something. And it’s the accumulation of many of these choices that make the piece what it is. Because all these things are linked. VistaVision was engineered in the early 1950s. It came about, it might have even come about the exact same year that the term “brutalism” was coined and those first buildings were erected in the U.K. in the early 1950s. So these things are all guided by a poetic logic. And even though I don’t expect audiences to know these things, or even literally interpret them, I do think that all audiences feel these things and there’s a sort of aura about them, and that’s what I yearn for in the medium. It’s like music. How many lyrics do you sing to yourself in a car and you don’t know precisely what they mean? Like if you’re listening to Ultravox, what is the significance of “Vienna” precisely? I’m not sure, but it seems very important to them. And it’s transcendent. And so I think that what happens with cinema is that there’s so many cooks in the kitchen that everything becomes very Land of the Literal. You have to defend “why?” and “would they…?” and I’m not really guided by this very literal logic. I’m guided by something else. I don’t make docudramas. I don’t make neorealistic movies. I like them very much. There’s many neorealist films that are very important to me. But there’s a lot of choices in this film that I thought to myself, “How would Michael Powell handle it?” For example, Guy Pearce’s character in the film is a capital-A antagonist that would have existed, could have been a James Mason or Joseph Cotten, and what was so great is that Guy really understood that, he imbued the character with nuance but he understood that for an antagonist in a 1950s melodrama, it was OK for him to play that note and play it very well, very consistently, but over and over again. In a way that really adheres to the style of performance from that time. And I think it’s just very important to have a philosophy about every aspect of the film, the performance, the music, for all of these things to sort of be simpatico. And still it might not result in something that everyone connects with, but there’s a real consistency and continuity of a vision that kind of forges the thing into being and gives it its form.

Olsen: In the film, something like, say, Guy’s character, the way he sort of just disappears from the movie in a somewhat unexplained fashion, is that the kind of thing where you then have to fight to hold on to the enigma and the ambiguity of that? Are you being asked, “Well, what happened to him?”

Corbet: Yeah, I’ve been asked. I think that it’s a pretty simple answer. I think that the whole idea was that there’s all of these characters in the film that keep disappearing from this character’s life. It happens first with this character that Adrien [Brody], he steps out on the deck of the ship before they see the Statue of Liberty and this character that he’s holding in his arms has clearly been important to him for at least the last couple of years. [This character] that he’s taken the boat over from Bremerhaven with, and then he leaves them on a bus. And the last person you see before the title is this character and holds on him for a moment, he actually looks in the camera, which I thought was really interesting. And we never see him again. And then with Alessandro Nivola, his character, at a certain point he disappears. And all these characters just kind of keep slipping away. And the whole film is sort of about the transient nature of being an immigrant, about life on the road. Everything that is important to you, near and dear to you, you just keep losing it over and over again, or it keeps being taken from you. So it made sense to me that it’s not only Guy that more or less, you know, disappears from the story. It’s also Adrien. At a certain point, it starts to shift its focus to Felicity’s character and ultimately to Zsófia, their niece. And the reason that is because for me, the film as it investigates legacy, this character’s body of work is not his legacy. His family is his legacy. The road that he’s paved for his niece, alongside his wife, that is his legacy. That’s the destination. And so I think that when Felicity, for lack of a better turn of phrase, calls Guy’s character out, I think that he’s just sort of robbed of any of the power that he once held over them and the family. And so it kind of doesn’t matter where he went. Like he could have just gone on a long walk. But obviously, there’s cause for concern. And the way that Joe Alwyn’s character responds seems to validate, perhaps, her accusation. So I think that everyone in the family is protecting some sort of a secret. And they’re at least very concerned that he’s hurt himself. But I also just wasn’t interested in seeing a pair of legs dangling from the ceiling. And I wasn’t interested in catching up with him on a long walk, because he doesn’t matter anymore. He’s served his dramatic purpose. And then the film shifts focus to the characters that actually the movie has been about the entire time. The movie opens with Zsófia and it closes with Zsófia, because it’s not about male ego. I mean, it’s an investigation of that to some extent, but the characters are written to their circumstance. The character is a middle-aged man because it was predominantly middle-aged men that were architects in the 1940s and ’50s.

Olsen: All three of your films grapple with real history and things that we actually know in the world, but then kind of warp them in some way, use them to dramatic effect. Do you see these films as some version of an alternate history? I’m just so fascinated by the relationship of these movies to the world that we know.

Corbet: Absolutely. First of all, I think a virtual history is a slightly more honest contract with the audience, because once you start writing, it all becomes fiction. I’ve spoken about this a lot over the years, but there was a moment when I was a teenager, and I was reading a biography, like a David McCullough biography or something. And there was just this moment when I realized, “There’s no way that anyone could know this.” I mean, it’s supported by years of research and David McCullough, for example, I think is a genius. But it is a story… So even if you are looking through the documents from the trial of Joan of Arc, or something, I’m sure that there’s occasionally context missing. So there was just this moment when I realized that the only way that I could make a historical picture was really to embrace it being a work of fiction.

I went to an architectural consultant named Jean-Louis Cohen. Sadly, he passed away recently. But he had written the book on Le Corbusier. He wrote “Architecture in Uniform,” which is a book about postwar psychology and postwar architecture. And I went to him with one question, which was, “I’ve written the screenplay. I want you to take a look at it to make sure that it doesn’t overlap too much with anyone that actually exists.” Because to my knowledge, there are no architects that got stuck in the quagmire of the Second World War. Certainly [not] architects out of the Bauhaus that survived the camps and then were able to go on to have any sort of career in the midcentury. And I left him with that question for a few days. He got back to me, and he said there are zero examples. There’s zero. And I found that incredibly disturbing. But it validated my initial impression. So the way that I thought about the film was when we went to the Bauhaus archives, and we looked at all of the unrealized propositions and blueprints from architects that did not have the status that people like Marcel Breuer had, where Walter Gropius was able to get the positions in the 1930s at universities and stuff. The reality is that, 95% of those visionaries, not only did many of them lose their lives, but all of them lost their livelihoods. And this film could somehow serve as a monument to the past and a monument to their unrealized work. This is sort of the poetic logic of the whole thing, and the way that I think about the film and actually the way that Daniel Libeskind recently, the extraordinary architect who’s designed many memorials, recently he wrote about the film and it was sent to me, and I was extremely moved by it because it was certainly the one interpretation of the film thus far that was the most in step with what we actually intended.

Olsen: In the epilogue of the film, the character of Zsófia, Laszlo’s niece, gives a speech where she, to some extent, explains the meaning of his work. And I can’t help but wonder, is that her saying something that he told her? Or is she in some way interpreting his work as a critic?

Corbet: Well, that’s the thing, right? They’re works of public art, just like the film. And so I really encourage audiences to interpret that however they might, because I think that art is interpreted and misinterpreted all the time. And so it’s certainly a reading of what it is that he intended. But there’s a sort of bluntness about the film’s conclusion. I’m interested in the dissemination of information — when a film can be very direct and which points the film can be quite enigmatic. And I think that there’s something kind of great for viewers, or hopefully it’s great for most viewers, that they just never have the film’s number. Like they never really have the rabbit by the foot. And I think that disorientation, it keeps the experience of watching the movie very alive for viewers. And it’s funny because I think that a critical analysis of it would be that the filmmakers completely lost the plot. Like it’s a runaway train. But what if it’s designed to be a runaway train? And that’s a place that I’ve been operating for a long time. I like a film to, at a certain point, become untethered by design. And I think that a lot of really interesting things happen for the viewer. It can be frustrating. It can be exciting. It can be all these things at once. And so I think it’s important that the film — I don’t make films to be universally loathed, but I don’t make them to be universally liked either. There has to be some sort of tug-of-war. I hope that couples are in the taxi ride home arguing about it.

Olsen: There’s been some controversy around the film from the use of AI in correcting the Hungarian pronunciation of some of the performers. Have you been surprised by what the response has been to the use of that technology?

Corbet: It’s funny to me because so many production companies make companies like our partners at Respeecher sign NDAs because of this being such a hot-button topic. But for us, it was obviously the only way to achieve something which was completely authentic. And for us, representing the nation of Hungary was incredibly important to us. So I wanted Hungarian viewers to be able to watch the film and the Hungarian dialogue, for it to be completely accurate, because you could practice the language for 45 years, and you would never speak it without an American accent or, in Felicity’s case, an English accent. It’s simply not possible. It’s one of the most difficult languages in the world.

And so, for me, I think that there is an absolutely ethical use of this technology and Respeecher in particular, a company that’s based in Kyiv, Ukraine, a group of engineers that worked on this in a manual fashion. I mean, this is us lining up sine waves, “Minority Report”-style, and seeing where a vowel or a syllable is sort of falling out of place and giving the actor’s accent away. It took us weeks and weeks to do, and it created jobs. It didn’t eliminate jobs. And finally, Adrien and Felicity, they own their vocal models in perpetuity. When we did this, I said, “I want you guys to have this so that if there ever is a copyright infringement issue for you in the future, that you actually own it.” I understand why people are concerned. I have some of those concerns as well. But I think that people are not clear on exactly what we did and how we did it.

The last thing I’d like to say about it is that there’s been a lot of confusion about the dialect, and I think there was confusion about where we used it in the film. It’s only used for offscreen Hungarian dialogue. The monologues, the letters, et cetera. That’s it. We didn’t use it for Felicity’s accent when she’s speaking English or Adrien’s accent when he’s speaking English. His family is from Hungary. He can actually speak Hungarian, and we never would have been able to actually get it there if he didn’t speak it as well as he spoke it. So it’s been just another wave in the ocean over the last six months. But it is what it is. And frankly, I would never have done it any other way. My daughter and I were watching “North by Northwest,” and there’s a sequence at the U.N., and my daughter is half Norwegian, and two characters are speaking to each other in Norwegian. My daughter said, “They’re speaking gibberish.” And we used to paint people brown, right? And I think that, for me, that’s a lot more offensive than using innovative technology and really brilliant engineers to help us make something perfect.

Olsen: Before I let you go, one last thing I want to ask you. You mentioned this earlier. At the Golden Globes, there was such a wonderful moment where you were speaking to your daughter from the stage. She was in the audience. She was crying. She later came up onstage with you. I can only imagine what it’s been like for you to be experiencing this award season, the response to the film, in part through her eyes, to have her along with you while this is all going on.

Corbet: I got back to the table, and she doesn’t cry very much. She’s been through a lot, actually, in the last few years. Had some scary family stuff and whatever. And she’s usually pretty stoic. So I got back to the table and I was like, “Are you OK?” And she just said, “I’m just so happy it’s finally over.” And I was like, Oh no. “Well, it’s not quite over.” So I had to sort of contextualize that it was going to be another couple of months. But I was like, “Yes, it’s sort of a light at the end of the tunnel.” But now we have two weeks left, and she’s coming with me everywhere. So I’ve been away from her for the last three weeks. I return home to New York, pick her up. We go to the BAFTAs together this weekend. And then we have the Academy Awards. And then it’s over. And the thing is that whatever the outcome of these things, it’s just really, it’s really great. I wrote to [“Anora” filmmaker] Sean Baker last night to congratulate him on the DGA and PGA wins. What’s so nice about about this season is that a lot of folks have been getting their flowers. And I love Sean’s movie and I love RaMell Ross’ movie. Like, I think RaMell is really a visionary, and it’s a very important movie for many, many reasons. And so just the fact that all of us have gotten this kind of lift from this attention, I think we’re all really grateful for it.

I mean, [“The Brutalist” has] made almost $25 million now globally. And for a film that is about what this is about, that’s 3 ½ hours long, I mean, what more could you ask for? And so I’m not just being nice when I say that we’ve already won and we got what we needed to out of this process. We squeezed all the juice out of the orange. So I’m just really grateful to our partners, because the thing that no one sees is that there’s an army of people that are making this all possible and navigating these campaigns. It’s its own production and it’s its own art form. And it’s something that I don’t do. And so it’s been really interesting for me. And I’ve got to say, I’m pretty impressed by our teams at A24 and Universal International. They know what they’re doing.