Few playwrights have made a greater impact on their countries or the world than Athol Fugard. Athol’s plays bore witness to the horrors of apartheid and brought the people affected by that brutal regime to life onstage. These stories stunned South Africans of conscience, appalled the Western world, and helped bring down the apartheid government.

The first play of his I saw was Sizwe Bansi Is Dead, which he co-created with John Kani and Winston Ntshona. I saw it at Chicago’s Goodman Stage Two in 1976, directed by Gregory Mosher. Two actors. Two chairs. A table. And a bare light bulb. It was like an earthquake. The audience’s silence at the end seemed to last a full minute, until we finally erupted into deafening applause. After the actors left the stage, many in the audience sat down again, utterly spent. I was one of those people, and I would never be the same.

My relationship with Athol didn’t become personal until a few years later. My play Still Life, which premiered under my direction at that same Goodman Stage Two in 1981, was then part of an international theatre festival at the Mark Taper Forum. Presented in the festival was Woza Albert!, a play written by Barney Simon and Mbongeni Ngema (Sarafina!). Mannie Mannim designed the lighting and Barney directed. The Still Life company saw Woza, the Woza company saw Still Life, and we immediately recognized we were soldiers in arms. Barney, who was artistic director of the Market Theatre in Johannesburg at the time, decided to direct Still Life there. Athol saw it. This is what he wrote about it, which I quote from his introduction to my anthology Testimonies, published by TCG:

Another challenging reunion with Barney—firstly his production of E.M.’s Still Life…powerful and very moving…and then a long talk about it and theatre in general afterward. In talking about Mann’s work, he used the word “testimony” several times—I made him check its dictionary definition: “To bear witness”…Barney became very worked up: “We can’t be silent! We must give evidence! We are witnesses!”

Though I had met Athol briefly after a preview of Master Harold on Broadway, it wasn’t until I was commissioned to write a miniseries on the life of Winnie Mandela that I spent extended time with him. I had told the producers that I could not write the screenplay from newspaper clippings and research. I had to go. I had to look into Winnie Mandela’s eyes and hear her story from her. They told me she was under house arrest and they didn’t know how to reach her. I called Barney; he called Mbongeni, who knew her well, and he introduced me to Peter Magubane, the great Black South African photographer, and one of Winnie’s best friends. Peter said he would meet with me, and if he approved, he would take me into Soweto to meet Winnie. I studied hard, passed his test, and I spent the next four weeks with her.

After my days with Winnie, I would often meet with Athol to talk about what I had learned. I had come to share his love for South Africa, and our friendship blossomed as we discussed Winnie’s struggle to survive and fight the apartheid regime. Those days were some of the most exhilarating, though dangerous, days of my life, and they gave me the courage to continue to dedicate my life to writing, directing, and producing plays and screenplays dedicated to social justice.

It should come as no surprise, then, that one of my first calls on becoming artistic director of McCarter Theatre in July 1990 was to call Athol Fugard to ask him if he wanted an artistic home in America. He joyously accepted, and we started a new chapter in our relationship. First, he directed a play of his called Hello and Goodbye with Maria Tucci and Zelko Ivanek, which was greeted with great acclaim.

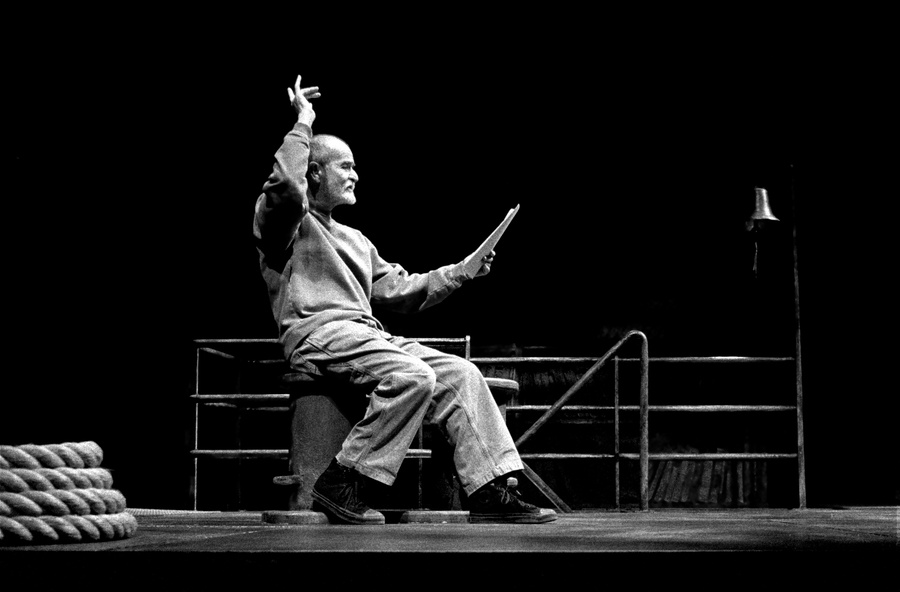

We then premiered three beautiful plays by Athol. He was struggling to find his subject post-apartheid, and he found it first in Valley Song, a poignant grandfather/granddaughter play set near his home. His granddaughter was played by Lisa Gay Hamilton, and Athol played the grandfather. He went on to write Captain’s Tiger and Sorrows and Rejoicings. In one of my later seasons, we brought over John Kani to direct his son Atandwa in the part his father created in Sizwe Bansi Is Dead. I delighted in seeing our audiences stunned as I had been stunned on my first viewing of that magnificent play.

Athol was a great man of the theatre, ferocious in his dedication and at the same time kind, modest, and attentive to all around him. Our managing director, Jeff Woodward, recalls, “Every day Athol was in rehearsal, he would enter the building and each day make the rounds greeting the staff. He would start with our receptionist and then wend his way down the administrative/artistic corridor, going into each office saying hello to the fundraisers, marketers, accountants, interns, literary managers, and box office, and then back to the production department area before arriving at the rehearsal hall. No artist ever had done this, and it inspired the entire staff.”

Athol is (not was) my inspiration, my moral compass, my hero, and my friend. He proved the adage “the pen is mightier than the sword.” He lived it, often at great cost. He fervently believed in the significant role of the artist in a society facing evil and injustice. I can hear the conversation between him and Barney Simon as if they are talking to us in the present: “We can’t be silent. We must give evidence. We are witnesses.”

I cannot but think he is watching us now as we witness our own country slide into white supremacy and authoritarianism. He showed us the way to resist. Athol is telling us all: We can’t be silent.

Emily Mann is an award-winning writer and director whose original plays include Execution of Justice, Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years, and Gloria: A Life. She served as artistic director of McCarter Theatre in Princeton, N.J., from 1990 to 2020.