To see Julia Phillips become the first female producer to win a best picture Oscar is to get a glimpse of the charisma and wit that made her so welcome in Hollywood, in boardrooms and on sets, until she wasn’t. At the 1974 Academy Awards, a streaker had interrupted David Niven introducing presenter Elizabeth Taylor, who stumbled over her lines, then announced “The Sting” as the winner. Phillips took the stage with her (not yet ex-) husband, Michael, and their co-producer Tony Bill. Phillips, with a touch of New York accent, said, “You can imagine what a trip this is for a Jewish girl from Great Neck. Tonight I get to win an Academy Award and meet Elizabeth Taylor all in the same moment.” Off-screen, Taylor guffaws.

The Ultimate Hollywood Bookshelf

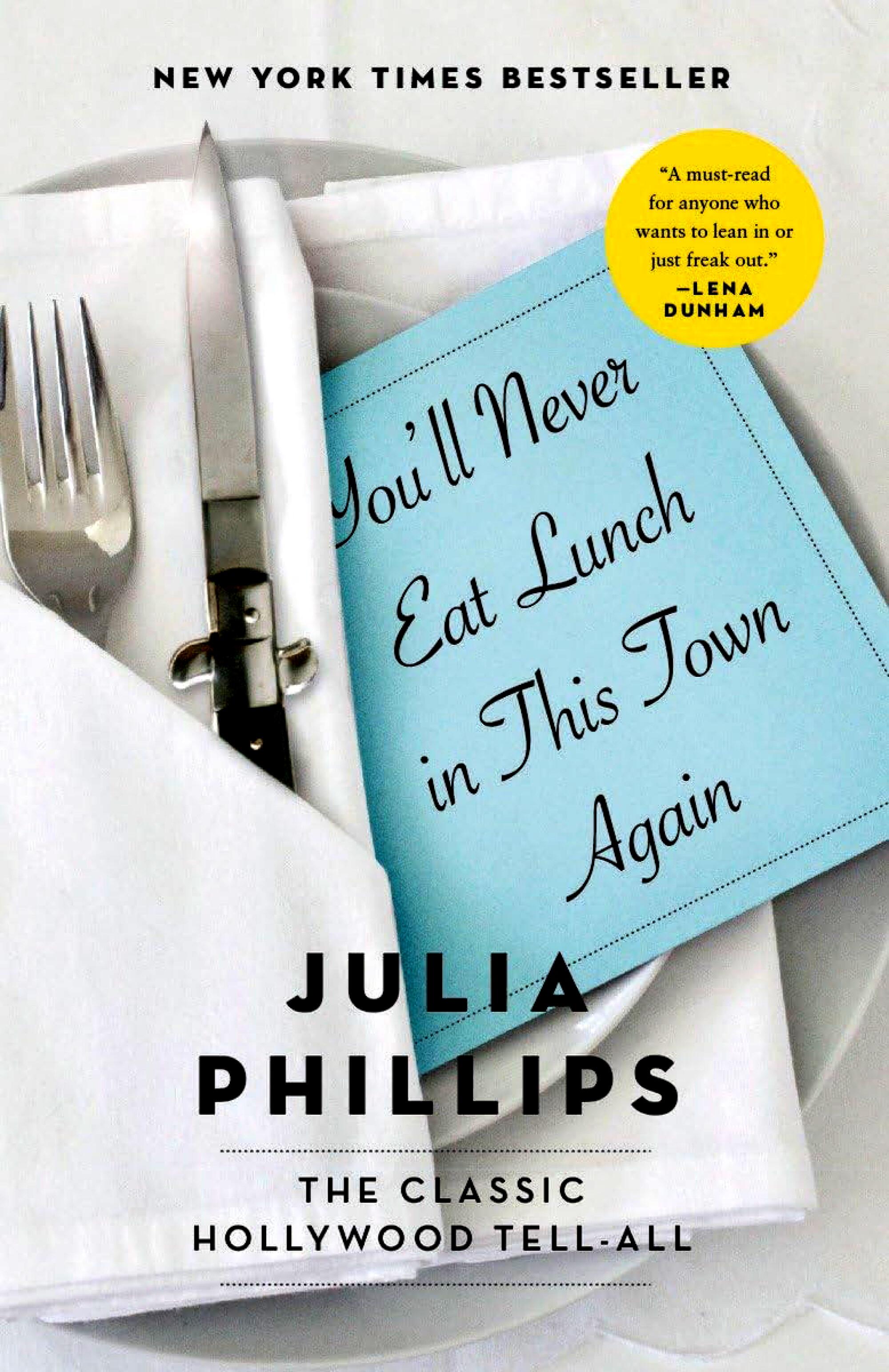

“You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again” ranks No. 31 on our list of the best Hollywood books of all time.

This scene opens “You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again,” Phillips’ 1991 memoir. What viewers couldn’t know, but what she catalogs cheerfully in the book, are the drugs she’d taken that day: “a diet pill, a small amount of coke, two joints, six halves of Valium, which makes three, and a glass-and-a-half of wine. So far.” Phillips would go on to produce “Taxi Driver” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” a genuinely stellar record. Then the cocaine took over. The word “freebase” appears in the index 16 times.

There is an apocryphal story that as the book landed on desks around Hollywood, everyone flipped to the index to see what Phillips had written about them. Swipes at stars such as Goldie Hawn and Warren Beatty made the news, but it was probably the frank and impolitic descriptions of such power players as Irving Azoff (“short,” “dangerous and powerful”) that cost her.

What few readers saw at the time is that this is an Icarus story. Phillips begins at her high point and then burns her way down. She is not looking for redemption or forgiveness. She is not apologizing. She had ambition and ego and blew millions of dollars on coke. Plenty of other people did too, but she decided to tell her story.

Although the book has a jumpy narrative — whether that’s having the form match the cocaine content or because after the year of legal vetting, some cuts went unpatched — it’s a straightforward memoir. Phillips was brought up by intellectuals in New York and had a troubled relationship with her mother. She started out in publishing, where she had a good eye; she met Michael, a stockbroker, and the two moved to California to get into the movies. They were money people who started out on the fringes, with an unfashionable beach address that, looking back, seems to be the center of everything. Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese hung out and celebrated New Year’s Eve there.

After the success of “The Sting,” doors flew open. Phillips gets the good table at Morton’s. She has the support of Columbia Pictures President David Begelman, whom she squeezes for more money each time “Close Encounters” needs it. She parties with Hawn and the Rolling Stones (and can’t resist criticizing them). She tries to adapt Erica Jong’s “Fear of Flying,” which she optioned and was to direct, but they fell out, and Jong sued her (Phillips writes that Jong looks like Miss Piggy). If the dropped names today feel a little like homework, Phillips’ fierce intelligence and ice-cold pen make it worth it.

Phillips was living furiously and fast on both coasts. She made very smart producer moves, such as screening a pre-release cut of “Taxi Driver” for Pauline Kael when the studio was threatening major cuts. She had a daughter and a divorce and a fondness for drugs.

She writes about doing freebase like she’s falling in love. Maybe she was. “This is just about the highest I’ve been …. Little bells keep going off in my legs, which feel as if they have been painted by Salvador Dali. Puffs of sensation ebb and flow, and here is the real attraction — they all seem in sync with the ebb and flow of the universe, the macro and micro of it all — the heartbeat of the cosmos in concert with mine.” Is it any wonder, really, that she wanted more and more of that? In the next scene, she is getting high while talking to producer Ray Stark on the phone. Is it any wonder that her balance couldn’t last?

The drugs almost killed her, and she credits her daughter’s innocence as being what brought her back. It’s remarkable that she retained enough to write this book. Although some would protest that she did not, for the most part it stood up to scrutiny. It is a brave, foolhardy and one-of-a-kind Hollywood memoir.

Kellogg, a writer and editor, is a former books editor at the L.A. Times.