To hear Herodotus tell it, a total solar eclipse in 585 BC ended a five-year war between ancient kingdoms in present-day Turkey.

Could another total eclipse on Monday bring an end to the partisan wars in America?

The idea may sound far-fetched — until you talk with Paul Piff. The UC Irvine professor of psychology and social behavior has spent the better part of two decades researching what triggers us to set our personal needs aside and shift our focus to the greater good.

One of them, he and other scholars have found, is awe: the feeling you get when you contemplate something that is so vast and so mysterious that it forces you to reevaluate your understanding of the world.

And few things generate awe like watching the moon blot out the sun and plunge a sunny day into erie darkness.

“People talk about eclipses as one of the coolest or most mind-blowing things they’ve ever seen,” Piff said.

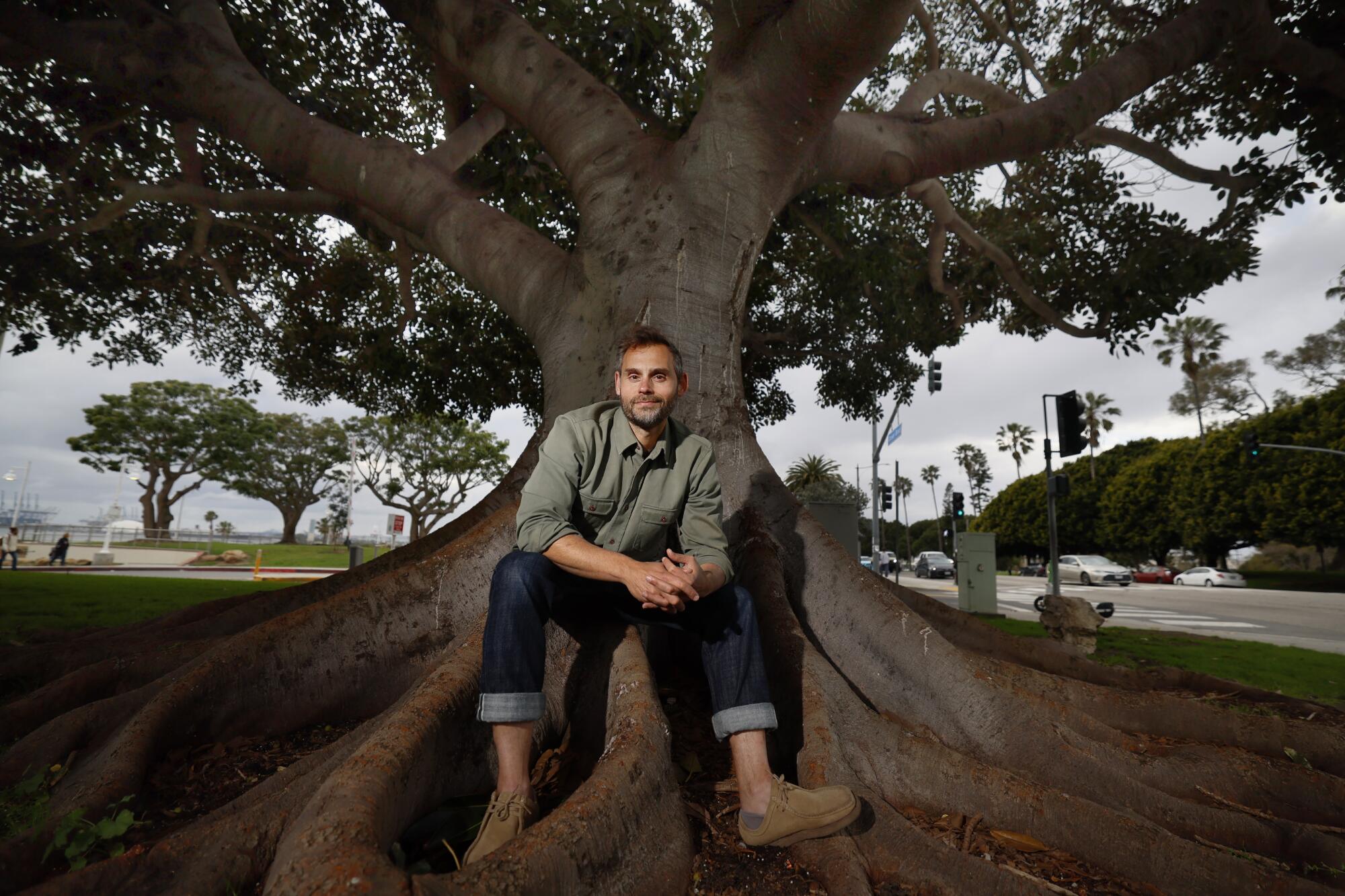

Paul Piff, a psychology professor at UC Irvine who studies awe, poses in Long Beach last week. He used the 2017 total solar eclipse to conduct research on what makes people feel awe and how it changes their emotional state. He’s planning another experiment based on the Monday eclipse.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

For the Great American Eclipse of 2017, Piff launched a research study that showed people engulfed by the moon’s shadow experienced more awe than their counterparts who didn’t see the sun disappear. What’s more, that sense of awe seemed to make them feel more in touch with others, more open to differing points of view, and more inclined to put someone else’s needs ahead of their own.

Piff is of the opinion that the country could use more of those sentiments this year, as a contentious presidential race threatens to turn political opponents into sworn enemies.

Awe “gives you a sense of feeling connected to something bigger than yourself, like your community, your society or your world,” he said. “Getting people to feel that way is totally vital to our species’ survival and longevity.”

Monday’s eclipse offers a fresh opportunity to assess the emotional states of the tens of millions of Americans who are expected to gather in the path of totality. Piff plans to focus on whether the celestial event will make those who experience it feel more allied with their fellow Americans who belong to a rival political party.

On Aug. 18, 2017, Poureal Long, a fourth-grader at Clardy Elementary School in Kansas City, Mo., practices the proper use of eclipse glasses in anticipation of an eclipse Aug. 21.

(Charlie Riedel / Associated Press)

Jennifer Stellar, a social psychologist who studies emotions at the University of Toronto, sees reason for optimism. She said awe is an ideal tool for trying to reduce political polarization.

Emotions like gratitude and compassion tend to pull one’s focus outward, but in those cases it’s usually redirected toward a single person, she said. Awe is unique in that “it creates a sense of interconnection, of common humanity, of collective interest.”

The community-oriented mind-set documented in the wake of the 2017 eclipse wore off within six weeks, Piff and his collaborators found.

What would it take to make it last?

If you’ve ever found yourself mired in an anger spiral, paralyzed with fear or overwhelmed by debilitating grief, you may have wondered what emotions are good for. Experts assure they serve a useful purpose.

“Negative emotions narrow your attention, get you to focus on threats. Positive emotions broaden your mind,” said psychologist Dacher Keltner, faculty director of the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.

Keltner’s lab has studied positive feelings like amusement, compassion, gratitude and love. But his favorite emotion is awe. (He even wrote a book about it called “Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life.”)

“Awe is destabilizing,” Keltner said. “It makes you realize your knowledge can’t explain everything.”

A person watches the moon pass between Earth and the sun during an eclipse Oct. 14, 2023, in Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah.

(Rick Bowmer / Associated Press)

Awe is also a universal emotion, expressed by people across countries and continents. No matter where we’re from, awe makes us widen our eyes and open our mouths.

The fact that it emerged in so many disparate cultures around the world is one indication of awe’s usefulness, Piff said. What’s more, societies have ritualized ways to get regular hits of awe, whether it’s walking into a majestic church or visiting the Grand Canyon.

When Piff investigates the effects of awe, he prompts study subjects to feel it by asking them to look up into the canopy of a stand of towering eucalyptus trees or by watching a slow-motion video of dye dropping into a glass of milk.

Such research by Piff and many others has found that awe makes us feel breathless, affects our heart rate, and causes goosebumps to rise on our skin. It also reduces physiological signs of stress and suppresses the brain’s default mode network, which plays a role in certain forms of self-focus.

“In all sorts of ways, individuals who experience awe experience a whole bunch of different benefits — better health, better meaning, more happiness, a greater sense of purpose in life,” Piff said.

It also fuels discovery and exploration, Keltner said.

“Awe provides the engine by which you update your knowledge,” he said. “It animates the testing of new ideas. And we need that — we need to always be updating our understanding of the world.”

Keltner has gathered stories about awe from 26 countries to look for common triggers. Nature was one of the broad categories that came up repeatedly, he said, and “big ideas” was another.

A total solar eclipse ticks both of those boxes.

A crowd looks up at the time of the solar eclipse in Salem, Ore., on Aug. 21, 2017.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times)

There’s nothing inherently mysterious about the cause of a total solar eclipse.

The moon travels around the Earth as the Earth travels around the sun, though the planes of those orbits are slightly askew. Nonetheless, at least twice a year the moon comes directly between the Earth and the sun, blocking it from view in the daytime sky. And about once every 18 months or so, this celestial alignment occurs while the moon is close enough to Earth to cover the sun completely — in other words, to totally eclipse it.

That seems like a frequent occurrence, but any particular spot on the planet will find itself in the path of totality just once every 375 years, on average. To find oneself in just the right place at just the right time may be awe-inducing all by itself.

The idea of using an eclipse as a natural experiment to study awe came to Piff in 2016, when he attended an “awe summit” and heard a UC Berkeley astronomer mention that the Great American Eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017, would be the first in nearly a century to produce a coast-to-coast path of totality.

The idea of using an eclipse as a natural experiment to study awe came to Paul Piff in 2016, when he attended an “awe summit.”

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

It wasn’t immediately clear how to capitalize on the event. He could have dispatched researchers to places along the eclipse’s path so they could observe the crowds or conduct interviews. He could have distributed a survey to people who said they’d witnessed the eclipse and hoped that they would fill it out.

“None of the ideas really stuck,” Piff said.

Ultimately, he turned to Twitter.

Nickolas M. Jones, who was a graduate student at the time, had devised a way to identify Twitter users in a particular community based on the accounts they followed. That allowed him to create a sample of more than 1.5 million tweets shared over a 12-week period by more than 22,000 people in select cities along the path of totality.

Meanwhile, another graduate student named Sean Goldy took the lead in creating a custom dictionary of words that expressed awe — it included “transcendent,” “mind-blowing” and “unreal” — along with terms indicative of the community-focused outlook that awe often inspires. The dictionary was used to assess the emotional subtext of the tweets Jones amassed, as well as a sample of 6 million tweets posted on the day of the eclipse.

The researchers found that Twitter users who were positioned to witness the eclipse were more than twice as likely to use words from the awe dictionary than people who missed out on the big event.

To a lesser degree, they were also more likely to use words that expressed a collective mind-set, recognized the limits of their knowledge, and gave credence to the views of others. The research team’s statistical analysis suggested that these feelings were driven in part by the awe they felt.

In addition, the tweets gathered by Jones showed that people who injected more awe-related words into their eclipse day tweets also used language infused with outward-looking, community-minded sentiments — although the effect was short-lived.

The findings were published in the journal Psychological Science.

The moon covers the sun during the total solar eclipse in the skies over Cerulean, Ky., on Aug. 21, 2017.

(Timothy D. Easley / Associated Press)

Jones, who is now a senior postdoctoral researcher at UC Irvine, said he developed his method of geolocating Twitter users in order to gauge the effect of mass shootings.

“The effect that we find when we study negative events is pretty powerful,” he said. “I was not expecting things to pan out really well for something positive, but … it worked!”

Posts on X, as Twitter is now known, are no longer freely available to researchers. So Piff and a new set of collaborators are devising another way to gather data related to Monday’s eclipse.

They’ve already found people who said they are planning to experience totality somewhere between Mazatlan, Mexico, and Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. They hope to entice them to answer a few questions on their phones while the world is temporarily dark, and to follow up with them for several weeks afterward.

In other experiments, Piff has had volunteers invest five minutes in a “daily intervention of awe.” Early results suggest it extends the benefits of an initial awesome experience, he said.

People gather near Redmond, Ore., to view the sun as it nears a total eclipse by the moon Aug. 21, 2017.

(Ted S. Warren / Associated Press)

“If people become a little more attentive to the awe-inspiring things around them, you would very likely get more persistent effects,” Piff said.

He said he hopes that would include the kind of mind-set shift that could help bridge the country’s increasingly toxic partisan divide.

There’s no reason why an event like the eclipse would cause people to change their party identity, Piff said, but it could make them more willing to compromise with their political opponents for the sake of a collective goal.

“Awe seems to trigger more kind, compassionate and empathic behavior,” he said. “It reminds you of the bigger things that we’re a part of.”