Viggo Mortensen was always drawn to the old piano in his grandparents’ house in Watertown, N.Y., 30 miles south of the Canadian border, the community where he lived after his parents divorced. Whenever he went over, he would sit down and play. He improvised melodies, usually imagining a scene or something visual.

“It was a comfortable place to be, and you could sort of travel with your imagination as you were playing,” the actor, 65, says via Zoom from his part-time home in Spain, the afternoon light spilling from the window behind him as he lights up a smoke. “Even as a kid, I liked doing that. I always related music to images. I would imagine being somewhere.”

It’s only too clear in hindsight that Mortensen was, essentially, scoring a movie in his mind.

Now he’s doing it for real. Mortensen has written and directed “The Dead Don’t Hurt,” a new western out Friday in which he also stars as a Danish immigrant handyman who leaves his bold new bride (Vicky Krieps) to serve in the Civil War. As if that weren’t enough hats to wear, Mortensen composed the music, performing several instruments on the score.

Mortensen, who also scored his 2020 directorial debut, “Falling,” joins a very exclusive club of directors who’ve created the music for their own films — from Charlie Chaplin and Clint Eastwood to Jeymes Samuel. But one doesn’t get the sense that this is some auteurist flex, or even simply a means to save on the music budget (as was the case for fellow club member John Carpenter). For Mortensen, who also does painting and photography and runs a micro publishing company, making music has always been a vital part of telling the story of his life.

Viggo Mortensen, director of “The Dead Don’t Hurt.”

(Justin Jun Lee / For The Times)

“He really is a total, complete artist,” says Elijah Wood, Mortensen’s “Lord of the Rings” co-star, on a Zoom call from his home in Highland Park. “Certainly, there are people who express themselves in different disciplines and have other interests, but he’s so accomplished in everything he does. And he’s very humble and quiet about it. He just does.”

As his acting career began to take off in the 1980s — his first big screen role was as an Amish man in Peter Weir’s “Witness” — Mortensen married punk singer Exene Cervenka of the Los Angeles band X after they played husband and wife in the 1987 televangelism satire “Salvation!” He wrote some lyrics with her, although his role in her career was mainly limited to taking the cover photos for her solo albums. Their union ended in 1992, but it produced a son, Henry, who became a skilled musician and “knows a lot more about punk rock music than I do,” Mortensen says, “even though I like it.”

Still, there was always something punk, or bohemian, about Mortensen onscreen — even though he was often cast as working-class, macho types: a drug dealer, a hitman. He played tough parts sensitively, and straight parts sideways.

A fateful moment came in the mid-’90s, when the producers of a spoken word album about Greek and Roman myths approached Mortensen to contribute a piece about Poseidon. He wrote and performed a water-themed poem and “crudely, with a little tape recorder, recorded some water sounds to go with it,” he says. “I mixed it in a half-assed way and sent it to the company.”

They sent it back, fully mixed, with some interesting guitar parts by an enigmatic musician whose stage name was Buckethead. Brian Patrick Carroll is an Anaheim native who wears an upside-down KFC bucket for a hat over his long curly locks and a white “Halloween” mask. Mortensen asked Buckethead if he wanted to collaborate and they met in the Chatsworth studio of Travis Dickerson.

Something sparked between Mortensen, with his improvisational and decidedly non-pop inclinations and poetic musings, and Buckethead, with his virtuosic shredding and duffel bag full of Japanese toys. Their first indie album was “One Less Thing to Worry About” in 1997 (long out of print), which featured a black-and-white photo of Mortensen eating a shoe on its cover.

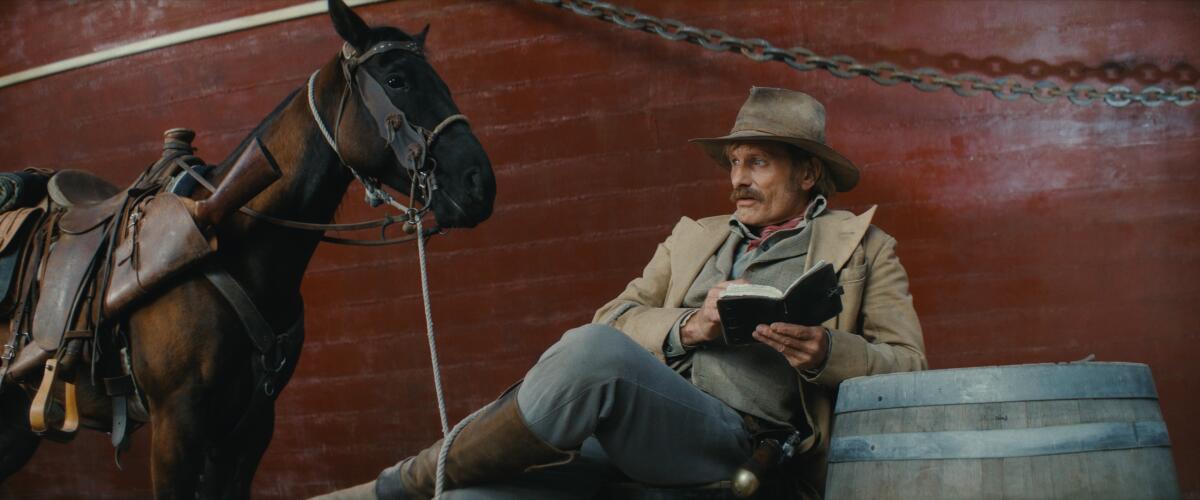

Viggo Mortensen in a scene from the movie “The Dead Don’t Hurt.”

(Marcel Zyskind)

“We’ve made several records since then,” says Mortensen, “all with Travis recording and laughing and just enjoying us clowning around. Some things are really odd to listen to, I guess. But every once in a while, we’d come up with a melody that was really beautiful.”

The whirlwind, impromptu sessions involved Mortensen’s son from the beginning. Afterward, “I would feel just very calm, almost like a really benevolent kind of drug or something I’d taken,” Mortensen says, laughing at himself. “I would drive home feeling really good, and then when we had the record finished, I would just listen to it over and over again — especially driving.”

Even when Mortensen found blockbuster fame as Aragorn in the “Rings” films, he kept making these weirdo soundscape albums. At the height of “Rings” fever, he roped his new co-stars — Wood, Dominic Monaghan and Billy Boyd — into contributing on a bizarre record called “pandemoniumfromamerica.”

Mortensen “invited us hobbits to laser tag,” Wood recalls, and then they all went over to Dickerson’s studio, where Buckethead and a bunch of instruments were scattered around the room. “It was just a couple of friends hanging out and messing around in the studio, and suddenly these things started to take shape out of the ether.”

On one track, “Half Fling,” Wood and Monaghan made “high-pitched, Muppet call-and-response voices,” says Wood. “I became aware instantly that the musical expression is not dissimilar from painting or photography for him. I don’t know that it even has an identifiable genre. I wouldn’t know how to classify it. It’s sort of beautifully undisciplined.”

“We did it for ourselves, really,” Mortensen says. “That’s how I see making art, generally — making it as a way of remembering what I’m experiencing at that time.”

That was the same impulse for Mortensen’s turn as a writer-director. “Falling” was inspired by memories of his mother and father, who divorced when he was young, and the dementia they both developed in older age.

Director Viggo Mortensen on the set of “The Dead Don’t Hurt.”

(Marcela Nava)

Based on his own original script, “The Dead Don’t Hurt” is a classic western in many respects. Mortensen plays the Danish-born Holger Olsen — his own father, Viggo Sr., was Danish and the actor still has family in Denmark — and Krieps plays Vivienne Le Coudy, a French Canadian woman with clear echoes of Mortensen’s mother, Grace Gamble, of Canadian descent. The story was born from his image of her running around in the maple forests near the Canadian border as a little girl.

Mortensen says he wrote the score as he was writing the screenplay, pegging where he thought music should go. He knew he wanted music of the period and reached out to violinist Scarlet Rivera — who famously played with Bob Dylan in the ’70s — and cellist Cameron Stone to perform his folky Americana ideas. They convened in the Chatsworth studio and Mortensen joined in on piano and also played bass, guitar and percussion.

When it came to shooting the movie, the score was as much of a guide as the script.

“I played the music for the cinematographer and for my first [assistant director] and some of the actors,” he says, “just to explain: This is the tone I’m going for and this will affect the duration of the scene, the rhythm of the scene and even shot selection. And because it’s a nonlinear story I knew there were going to be transitions from one time period to another, or ellipses. I knew the music would help.”

The sharp sound of clacking claves accompanies Mortensen’s character in the present day, hunting down the man who preyed on his wife during his military absence. Warm fiddle tunes and sweet harmonies underscore happier times in their marriage. Mortensen’s melodic score has a tactile, earthy feel that perfectly suits the steep trails, canyons and rustic production design. (Stunning locations in Durango, Mexico, stood in for Nevada.)

“I don’t like it when the music in a movie is telling you, ‘Now you must be afraid. Now you must be sad. Now you must be happy,’” the actor-director-composer says, “any more than I like it when the dialogue does that or the acting or the cinematography. So the idea was to have all the music before, and know what we were aiming to get across — but that it would accompany, and sometimes be in contrast, in the right moment, to what was happening.”

Mortensen says he might hire a different composer for the next movie he directs. He’s aware of his own limitations. Regardless, he’ll involve them early.

But whenever he comes across a piano — in a hotel, a restaurant or in a holding area on the set of “Eastern Promises” — he’s going to sit down and play it.

“Even if you just play for two minutes,” he says, “it brings you back down, puts your feet on the ground” — and it lets Mortensen’s imagination wander off into some new world.