The start of the 1990s saw an explosion of gay and lesbian films that defied convention. They mixed postmodern sensibilities with contemporary anxieties about everything from the AIDS epidemic to rampant homophobia. Furthermore, they refracted those concerns through a visual language that borrowed gleefully from the avant-garde and video art yet proved surprisingly marketable.

These were movies hard to label and harder still to ignore. To film critic and scholar B. Ruby Rich, that crop of films represented a period in cinema like none that had come before it — and perhaps since.

“It marked a moment when filmmakers — at whatever risk — were willing to make films that would galvanize people’s attention to injustice and death,” Rich, 76, tells the Times over Zoom from Paris. “And that’s why they still have power.”

Famously, Rich called it New Queer Cinema, a term that’s stuck. Those movies are to be celebrated in an upcoming series at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, “Full of Pleasure: The Beginnings of New Queer Cinema.”

Guinevere Turner, left, and Cheryl Dunye in the 1996 romantic comedy “The Watermelon Woman.”

(Academy Museum)

The showcase, which kicks off June 15, will be screening titles such as Derek Jarman’s melancholy regal drama “Edward II,” Todd Haynes’ controversial feature debut “Poison” and Cheryl Dunye’s groundbreaking “The Watermelon Woman,” films and filmmakers that ushered in a pivotal juncture in independent cinema by and for the LGBTQ community.

Gay directors were producing exciting, innovative work that was taking the festival circuit by storm. United neither by approach nor aesthetics, Rich identified them more as embodying a common style. “Call it ‘Homo Pomo,’” she wrote in 1992.

No sooner had the Village Voice published Rich’s ambitious overview of this budding canon than Britain’s film magazine Sight and Sound reprinted it and used it as the cornerstone of a conference at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Shortly thereafter, the U.K.’s Channel 4 did a special on it.

“Then it got picked up by distributors and theaters,” Rich recalls. “And it became a way to promote films that were part of this energy that I had named. It turned out to have this radioactive half-life and has just kept going, which is very lovely.” (As for her own fame for adding to the lexicon, she is self-deprecating: “I discovered something as a writer then: If you write a hook that turns out to be useful for marketing, you can live forever.”)

Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix in Gus Van Sant’s 1991 drama “My Own Private Idaho.”

(Academy Museum)

Rich remembers the era well. Living in New York City, she was watching academics wrestle with “queer,” then still a derogatory term, at conferences and in classrooms, while protest groups like ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, and Queer Nation were reclaiming the word as they papered the streets in response to government inaction over the AIDS epidemic.

“I had these two dimensions to this word that were perfect for me,” Rich says. “It was about spinning out this thing called ‘queer theory’ and what that would mean, what it was grounded in and what it could illuminate. But almost at the same minute, it became ‘We’re here, we’re queer! Get used to it!’ It became a kind of activist rallying call.”

As she watched the wryly erotic work of Gus Van Sant, the poetic and urgent sensibility of Isaac Julien, the anarchic energy of Gregg Araki, the sharp satire of Cheryl Dunye’s videos at festivals like Sundance and Lincoln Center’s New Directors/New Films, Rich felt emboldened to coin a phrase that remains as provocative now as it was revelatory back then.

“If the films hadn’t been so important, and if the filmmakers hadn’t kept making work, and if they hadn’t been joined by other wonderful filmmakers, I think this would have faded away,” Rich adds.

The explosion of cinema Rich was describing was unprecedented.

“You could not go to movie theaters and see gay films at that time,” she says. “There were very few, apart from Fassbinder. They had to be subtitled or else you couldn’t see them. And this changed that forever. It changed it so much that it became commonplace and nothing special and I’ll just wait till it’s on Netflix or whatever. But I think that the fact of having gay films, gay sex, lesbian romance, all of that on big screens at your multiplex, was absolutely earth-shattering for people at that time.”

An image from Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary “Paris Is Burning.”

(Academy Museum)

New Queer Cinema was all the rage. It was of and for the moment. In January 1991 at Sundance, Haynes’ “Poison,” a sci-fi-horror triptych inspired by the novels of Jean Genet, and director Jennie Livingston‘s “Paris Is Burning,” a documentary about ball culture in New York City, took top honors from its juries. A few months later, Van Sant’s street-hustler road trip drama “My Own Private Idaho” left the 1991 Venice International Film Festival with stellar reviews and a best actor award for the incandescent River Phoenix.

Hitting a chord with critics and audiences alike (Van Sant’s movie went on to gross $8 million, Livingston’s doc $3.7 million), these films remain urgent and current, as the Academy Museum series proves.

Part of that has to do with how early 1990s in-your-face filmmaking can still shock. The movies embraced pastiche, appropriation and irony. In doing so, they created exciting new ways of telling gay and lesbian stories. And did so by abrasively pushing back against the neat confines of identity politics. To merely call them “gay films” would have been insufficient. As Rich wrote then, these movies were “irreverent, energetic, alternately minimalist and excessive. Above all, they’re full of pleasure. They’re here, they’re queer, get hip to them.”

It’s those very lines that give the Academy Museum screening series its title. In addition to featuring early work from Keanu Reeves (“My Own Private Idaho”) and Tilda Swinton (“Edward II”), the series spotlights lesser known and discussed films. That includes Araki’s raucous 1992 road movie “The Living End,” which centers on two HIV-positive gay men on the run, and Rose Troche’s 1994 lesbian comedy “Go Fish,” which was rightly credited with making sure the new canon being enshrined wasn’t an all-boys’ club. There is pain in these films but also plenty of laughter and joy.

“It was experienced like a flash of pleasure,” Rich says. “Almost like the flash of green, legendarily at sunset. It was a kind of jolt. A kind of shot in the arm. Like ‘OK, we can do this,’ you know? ‘Here’s some candy. And now back to the front lines.’”

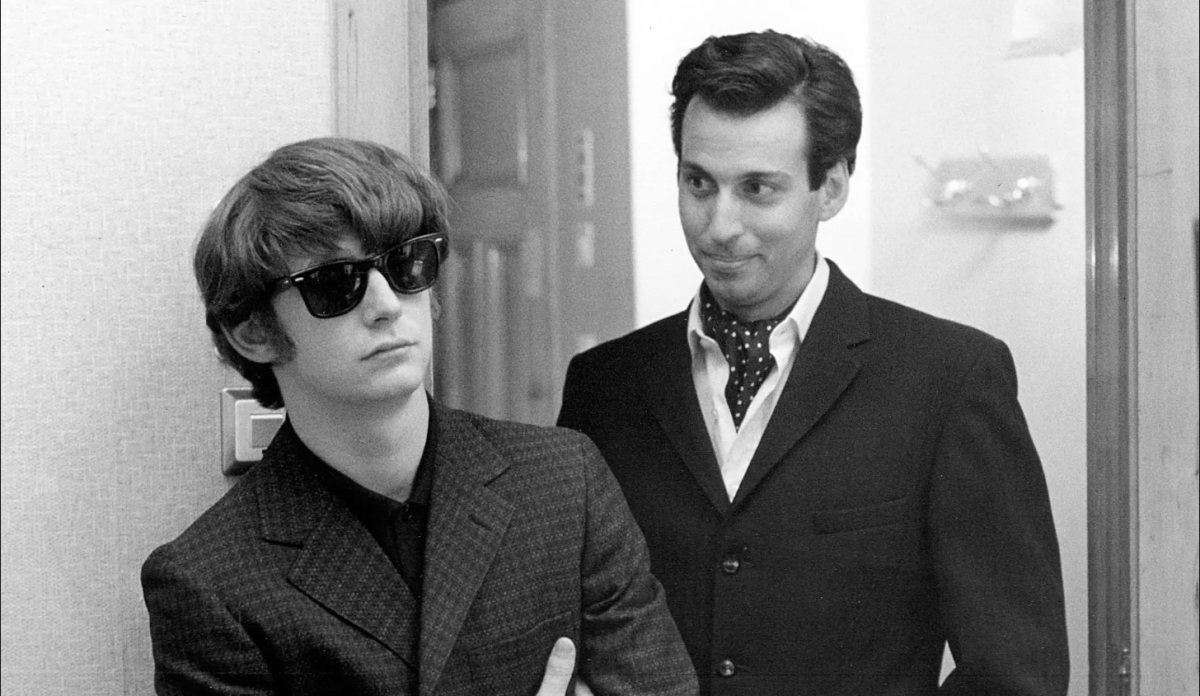

Ian Hart, left, and David Angus in the 1991 movie “The Hours and the Times.”

(Academy Museum)

What was inspiring about those films, she adds, was the way they were willing to give pleasure — and enact it onscreen — at a time when it was in short supply. Academy Museum series curator K.J. Relth-Miller’s re-assembly of this crackling cinematic wave is an apt opportunity to revisit those pleasures with the vantage of a few decades’ worth of hindsight.

“People were so beaten down by the horrors of AIDS,” Rich remembers. “In 1992, we still had no cocktail. Still had no cure. AZT was coming along but there were big fights over whether to take it or not. People were still dying. So it wasn’t the celebration of the end of an epidemic. It was kind of a rest stop, a kind of breathing room for people to kind of count their losses and try to figure out how to create a space of relief and even pleasure in the midst of that sorrow.”

New Queer Cinema’s filmmakers transformed that pain into glittering wake-up calls that forced audiences, critics, distributors and even fellow artists to pay attention.

“These films were a rallying cry,” Rich says. “You felt the joyousness of their arrival in the world. They cleared this space for themselves. They kind of put up their own klieg lights. It wasn’t pleasure without pain. I think that tricky balance was always there.”

You can see that balance at work in the beauty of Ellen Kuras’ gorgeous black-and-white cinematography for Tom Kalin’s murder-obsessed “Swoon” (1992), a film Rich says put the “homo back in homicide.” That ability to turn pain and heartbreak into stirring cinematic images remains a hallmark of this generation of filmmakers.

Does their legacy continue? Rich is quick to single out Paul B. Preciado’s 2023 Virginia Woolf-infused “Orlando, My Political Biography” as an outright masterpiece of trans cinema. (The docu-essay is coming to the Criterion Collection’s Janus Contemporaries label at the end of June.) “We need so many more films like that, on other issues as well as about queer or trans life,” she says.

Looking at the current cinematic landscape, she can’t quite bring herself to be too optimistic. “It’s amazing to me the extent to which the film industry has failed us in not making films about the horrors of the modern world,” Rich says. “It has just turned its back and made entertainment.”

Therein lies the still-prickly promise of projects like the Beatles-in-ascent period piece “The Hours and Times” and the Brit-punk drama “Young Soul Rebels” — both of which can be seen as part of the Academy Museum’s series.

“These films stand as a kind of monument to a period as much as they do to a reinvention of a medium,” Rich offers. “I think that’s why they last. Nobody’s really outdone them yet. They’re still raw. And there’s still a place for them.”