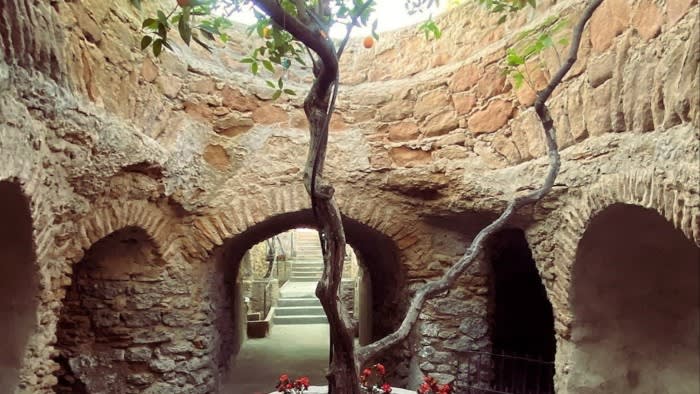

In 1905, Fresno, California experienced its hottest recorded temperature to date — 115F (46C). The following year, the Sicilian immigrant Baldassare Forestiere began to tunnel beneath his 80 acres of sun-baked hardpan soil to build an idiosyncratic escape from the heat. He had tried to establish orchards but the hard soil made it almost impossible. Instead, he went underground — establishing about 20 acres of tunnels that became his subterranean home, with a network of fruit trees and open-air courtyards known today as the Forestiere Underground Gardens.

Forestiere spent his first few years in the US working on subways and aqueducts on the east coast, where he gained his tunnelling expertise. His dream of an orchard brought him west to California. He continued expanding his tunnels single-mindedly and almost single-handedly there for 40 years until his death in 1946.

His extensive garden was mostly focused on food production, including citrus trees and small vegetable and herb gardens. He also cultivated “grapes, pomegranates, carob, loquats, jujubes, tamarisk, quince, arbutus berries, mulberries, Italian pears, figs, olives and almonds,” says Shera Frantzman, the gardens’ director of operations. He experimented with grafting and created one tree with seven fruits.

Knowing that the lower levels would involve a significant drop in temperature, “Forestiere also developed his underground areas to encourage airflow to make it even cooler and keep the air underground fresh”, explains Frantzman. “He designed a number of his skylights using the Venturi effect [regulating airflow and pressure through spatial constriction] and made breezeways to push air through the passageways.”

As a result, according to Frantzman, the Forestiere Gardens are typically 10F-20F (5.5C-11C) cooler than the surface. This is partly due to depth — the lowest points of the tunnels are about 25ft below ground, with multiple levels that include a glass-bottomed fishpond.

Forestiere hoped to turn part of his home into a restaurant so that others could enjoy the space he described as “singolare come il mare”: as unique as the sea. To this end, he tunnelled a drivable entrance for cars, built a terrazzo-tiled ballroom (posthumously finished by his brother) and designed tables with dwarf orange trees planted in the centre that could provide part of a meal.

Forestiere’s cavernous reply to the Central Valley’s intense summers is an impressive testament to one man’s ingenuity — and an interesting approach to adapting to rising temperatures. California’s 2022 extreme heat action plan predicted that “every corner of the state will be impacted . . . by higher average temperatures and more frequent and severe heatwaves,” with average annual temperature increases already 1F-2F in most of the state. As climate change introduces more extreme and uncertain weather patterns, horticultural experts are researching new ways to adapt.

Their prevailing advice is to plant appropriately for the climate. “Picking something that is well-suited to the conditions that you’re growing in is one of the best things you can do”, says Phoebe Gordon, orchard systems adviser for the University of California’s Agriculture and Natural Resources (UCANR) division.

UCANR runs a model Garden of the Sun in Fresno and advises farmers and gardeners on best practice, including how to cope with extreme heat. Their public garden includes demonstration areas, a “low-maintenance garden” and a planted area in the shadow of a redwood tree to mimic a shaded microclimate.

The nearby Clovis Botanical Garden, with Mediterranean and cactus gardens, puts water conservation education at the centre of its mission. John Pape, an arborist and horticulturalist who helped to found the volunteer-run garden, says it was conceived as “a place where people could go see plant material that [would] do well here” with minimum irrigation.

The “right plant in the right place” is a common saying, and in California, this typically means native, drought-resistant or heat-tolerant plants suited to its Mediterranean climate, which it shares with parts of Australia, central Chile, the Western Cape of South Africa, and the Mediterranean basin. Pape describes it as a “climate where it rains and is cool to cold in the wintertime, and where it is hot and dry with no precipitation to speak of during the summertime”.

During heatwaves, plants may slow their growth, drop flowers or stop flowering altogether. Water evaporation — which increases in hot conditions — is an important cooling mechanism for plants, but losing too much will cause them to wilt, and they can burn in too much sun.

Home gardeners can take measures to avoid excess evaporation such as mulching, using drip irrigation systems and watering in advance of heatwaves. Drought-tolerant plants should be watered according to their own needs — as should trees, to preserve their important role as shade cover.

Pape also encourages creative thinking about water use. “Everybody really needs to be thinking about how to plant the plant material and irrigation systems that use less water,” he says. This includes smaller lawns, and Californians getting “more comfortable with plants that maybe look a little wilder — it’s an aesthetic thing,” he says. “A lot of people think it should look like England here.”

Gordon agrees that thinking differently about landscaping is important: “We don’t even necessarily have to change how our landscapes look a lot, but just more mindful choices of what we’re planting could go a long way.”

Solutions such as shade cloth and lath houses also help in some circumstances. “There is probably some interesting work that can be done with shade because the amount of light that hits a plant is actually a lot more than it needs”, says Gordon. “Depending on the plant species, they will maximise photosynthesis at about half of the intensity of sunlight that hits them, at least in a really sunny area like the Central Valley. The rest of it actually has to be dissipated through antioxidants”. Studies, including one from Christopher Chen at UCANR, have shown that coloured shade netting and shade film can be useful tools for mitigating sun damage in California vineyards.

But there are trade-offs. The structure of the Underground Gardens “limits the amount of time that plants are in direct sunlight, which can help with stress, but it also reduces the amount of time that they’re photosynthesising”, says Gordon. The result can be lower fruiting productivity. Further research into plants’ stress tolerance is also needed, as orchard crops in California have mostly been chosen for their high yield rather than resilience.

There are technology-based alternatives, too. South in Paso Robles, Sensorio — which began as artist Bruce Munro’s installation “Field of Light” in 2019 — offers a night-blooming garden inspired by Munro’s experience of night in the Australian desert. The glowing, solar-powered fields bloom after absorbing the light of day.

“Climate change is going to change a lot of things,” Gordon says. Though it brings many challenges, “There are a lot of areas for us to improve and a lot of cool innovations that are probably going to happen . . . There’s a lot of room for adaptation.”

The City of Thousand Oaks, in Ventura County, advises gardeners looking for guidance on heat that “the most successful long-term strategy is to adapt to a changing climate”. Last year, Fresno set a new record of 69 days of triple-digit temperatures, with the highest recorded day at 109F (43C).

Though most people may want to remain above ground, there is something to be learnt from Forestiere’s persistence, too. Frantzman admires his “seemingly endless motivation to continue with the expansion of his Underground Gardens for decades. He was always coming up with new ideas and finding ways to overcome the obstacles he faced.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on X or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram