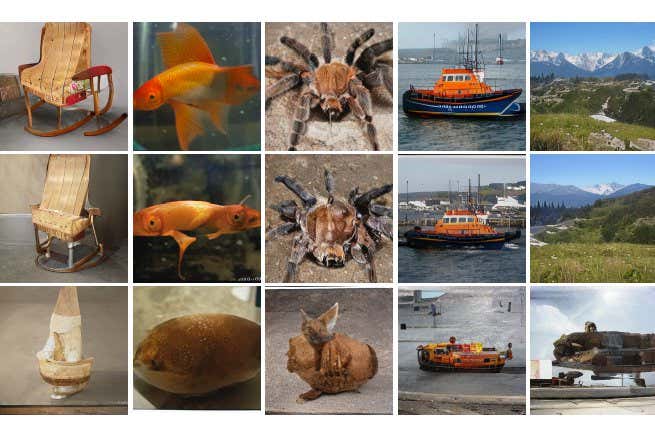

Top row: original images. Second row: images reconstructed by AI based on brain recordings from a macaque. Bottom row: images reconstructed by the AI system without an attention mechanism

Thirza Dado et al.

Artificial intelligence systems can now create remarkably accurate reconstructions of what someone is looking at based on recordings of their brain activity. These reconstructed images are greatly improved when the AI learns which parts of the brain to pay attention to.

“As far as I know, these are the closest, most accurate reconstructions,” says Umut Güçlü at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

Güçlü’s team is one of several around the world using AI systems to work out what animals or people are seeing from brain recordings and scans. In one previous study, his team used a functional MRI (fMRI) scanner to record the brain activity of three people as they were shown a series of photographs.

In another study, the team used implanted electrode arrays to directly record the brain activity of a single macaque monkey as it looked at AI-generated images. This implant was done for other purposes by another team, says Güçlü’s colleague Thirza Dado, also at Radboud University. “The macaque was not implanted so that we can do reconstruction of perception,” she says. “That is not a good argument to do surgery on animals.”

The team has now reanalysed the data from these previous studies using an improved AI system that can learn which parts of the brain it should pay most attention to.

“Basically, the AI is learning when interpreting the brain signals where it should direct its attention,” says Güçlü. “Of course, that reflects in a way what that brain signal captures in the environment.”

With the direct recordings of brain activity, some of the reconstructed images are now remarkably close to the images that the macaque saw, which were produced by the StyleGAN-XL image-generating AI. However, it is easier to reconstruct AI-generated images than real ones, says Dado, as the brain-interpreting AI can learn from its training data how those images were assembled.

With the fMRI scans, there was also a marked improvement when the attention-directing system was used, but the reconstructed images were less accurate than those involving the macaque. This is partly because real photographs were used, but reconstructing images from fMRI scans is also much harder, says Dado. “It’s non-invasive, but very noisy.”

The team’s ultimate aim is to create better brain implants for restoring vision by stimulating high-level parts of the vision system that represent objects rather than simply presenting patterns of light.

“You can directly stimulate that part that corresponds to a dog, for example,” says Güçlü. “In that way, we can create much richer visual experiences that are closer to those of sighted individuals.”

Topics: