Book review

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

By Ann Powers

Dey Street Books: 448 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Last year someone I was talking to snorted that an older, lefty, white woman we both know seemed “like the kind of person who goes to Joni Mitchell concerts.” I had just gotten back from a “Joni Jam” the then-79-year-old Canadian American singer-songwriter had put on with Brandi Carlile and a coterie of musicians at the Gorge in Washington state, eight years after a brain aneurysm had robbed her of her ability to speak and walk. Huddling with some 20,000 devotees under a pink sky at Mitchell’s first ticketed live performance in more than 20 years is a night I consider a peak life experience, and the snide comment reducing the artist and her fans to a stock type annoyed me. But having neither a smart response nor the energy to clap back, I kept my mouth shut.

Happily, Ann Powers’ book, “Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell,” has prepared me for my next such encounter, both intellectually and energetically. Better than that, it has helped me understand my own fandom and the brilliant but flawed, relatable but unknowable woman who inspires it. Powers writes about those who callowly dismiss Mitchell, but she also describes the way some of Mitchell’s fans have held onto the influential singer-songwriter over the years as a “smothering hug,” a kind of adoration that leaves the receiver no room to maneuver, no space to breathe.

Author Ann Powers

(Emily April Allen)

By contrast Powers, who is NPR’s music critic and the L.A. Times’ former critic, came to the subject of Mitchell reluctantly. The author writes that “all the Joni worship freaked me out, frankly,” and she was recruited to the book by an editor. This makes Powers the perfect writer for her subject, and she shows us a far more interesting way to regard Mitchell than the fan’s smothering hug. Hers is a loose embrace with the respect for craft that comes from truly understanding what it takes to write a song like “Woodstock” or “A Case of You” or “Come in From the Cold,” as well as a healthy dose of skepticism about the myth of Joni.

Mitchell is one of a handful of women in her era who were invited into the music world’s clubby little definition of genius, and Powers has the chops to explain exactly why that was so, both through her virtuosic writing on Mitchell’s musicianship and creativity and through a sophisticated interrogation of the gender and race politics of the era. She shows us how we can love an artist like Mitchell and let her be human, too, how we can understand her genius from — forgive me, Joni — both sides now.

For many Mitchell fans, the basic beats of her life are well known, from a defining childhood bout with polio, to the daughter she bore and gave up for adoption at age 21, to her romances with male muses like Leonard Cohen and Graham Nash, as she traveled from Saskatoon, Canada, to Laurel Canyon to Greece. Powers takes us to those places with Mitchell but finds a way to make the journey new, in part by gracefully interweaving her own history with Mitchell’s, including their shared status as mothers in adoptive triads — Powers adopted a baby daughter.

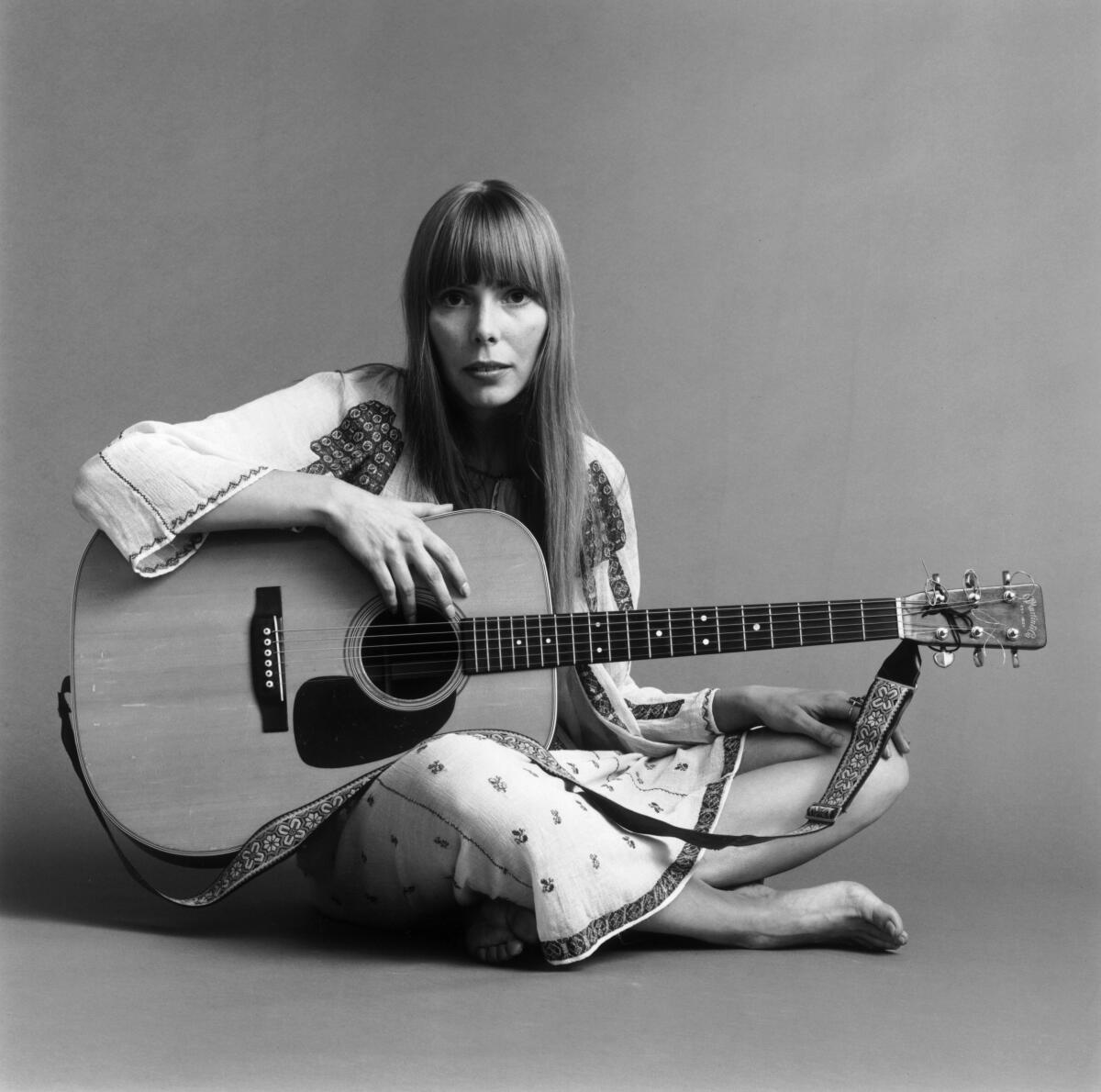

Joni Mitchell in 1968, at a fashion shoot for Vogue.

(Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive via Getty Images)

Both women have resisted the attempts of their male-dominated industry to pigeonhole them as female artists and metaphorical mommies, and both have grappled, in their own ways, with what it means to be a “real” mother. Rather than reach for easy answers to the questions about Mitchell’s maternity story, Powers manages to make a deeper point by accepting every woman’s essential fluidity on the topic of motherhood. “To ask whether Joni Mitchell ever wanted to be a mother is to assume that she, like any woman, could only hold one desire within her body at any given time, much less over time,” she writes.

Powers isn’t a biographer, she asserts on Page 2, she’s a critic, and she didn’t ever interview Mitchell for this book. That status frees her to write in a way that doesn’t trade creative independence for access. This approach is especially helpful when she’s tackling Mitchell’s uncomfortable history on the subject of race. A white songwriter who collaborated with Black artists such as Charles Mingus and Herbie Hancock and who has counted Stevie Wonder and Prince among her fans, Mitchell took great pride in crossing musical boundaries. But over her life and career she also made choices that feel cringey at best and racist at worst.

She seemed to think her appreciation of Black music entitled her to use the N-word in conversation and don blackface in a pimp-inspired persona she created named Art Nouveau, a character she posed as on the cover of her 1977 album “Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter.” She has never apologized nor fully explained. Lesser writers would tread lightly here — zipping past an issue that doesn’t fit neatly into the laurel-collecting stage of Mitchell’s career with an “it-was-the-’70s” dismissal. Or they might make canceling Mitchell the entire point of their book.

Singer Joni Mitchell sits under a fig tree in the courtyard of her Bel Air home. She said that a bird dropped a seed in the spot and the result was the fig tree.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Instead, Powers does the hard work of exploring what motivated Mitchell and why she has so often gotten a pass for her judgment when it comes to the Art Nouveau character. The music industry’s sister evils of sexism and racism have something to do with Mitchell’s adoption of this misguided muse. Powers enlists other thinkers to help her tackle the question, such as Queens College scholar Miles Grier, including a transcript of their conversation that begins with the author confessing, “Miles, I really need help here.”

As a critic, Powers works in a field where confidently taking a side is the game — thumbs up or thumbs down. But she’s especially insightful and fun to read when she gives herself and her readers permission not to know things. What a relief in this era of passionate intensity! It’s also a fitting approach to Mitchell and her work, which has always been about inquiry, about the journey of understanding ourselves and others, not about getting to the moment where we finally have life all figured out.

Reading Powers is like hearing one of Mitchell’s signature open tuning chords, an adaptation she developed because of polio’s effects on her left hand. The book, like the chord, doesn’t resolve neatly — it asks questions that ring on.

Rebecca Keegan is the senior film editor at The Hollywood Reporter, the author of “The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron” and co-author of “Young Frankenstein: The Story of the Making of the Film.”