New York has long been home to a vibrant community of Irish artists. As early as the 1910s, in fact, three different Irish-focused companies—the Irish Theatre of America, the Celtic Players, and the Irish Players—were producing work. “The community theatre idea has all at once come to life,” reported The New York Times on Feb. 14, 1915, with the announcement of the Irish Theatre of America.

Where the other two companies would often bring work from Ireland and sought to tell more historical tales, the Irish Theatre of America wanted to focus on the modern Irish experience. “If the Irish Theatre of America is to flourish,” its founders wrote in a press statement, “it must be rooted in Irish life here.” Rather than looking to playwrights and actors abroad, they intended “to call on the people around to produce the bulk of our plays.”

A hundred years later, the Irish artistic community in New York is in one sense flourishing, with multiple companies and a gorgeous new Irish Arts Center on 11th Avenue. Yet the question of material raised a century earlier by the Irish Theatre of America remains stubbornly relevant.

“It feels like often we are in a position where the only opportunities for us are in classic plays or working in adaptations,” said Colm Summers, artistic director of the New York-based Working Theater. Nicola Murphy Dubey, director of audience and new-play development at the Irish Repertory Theatre, agreed: “It’s important to hear from the broad spectrum of Irishness that we now have, that we’re representing a modern Ireland, a contemporary Ireland.”

As an Irish-born artist who has been in the U.S. for decades, Michael “Mick” Mellamphy has seen new work struggle to find a home in New York. “I used to run an Irish pub,” he told me. An upstairs space for play readings, he soon discovered, was in practice “a space where plays would come to die.” There was just too little infrastructure and support for writers to take new work to the next stage.

Cork-born writer/actor Sarah Street had a similar experience. “I could see that there were tons of new Irish writers here writing, creating, doing readings of their work,” she said. “But there was no space for us to develop work together and give it the push that it needs to be produced here or somewhere else.” After Mellamphy became the artistic director of Origin Theatre, which focuses on Irish theatre and presents a yearly festival of new work, Street proposed the creation of a fellowship to support a group of original voices from the Irish diaspora. They dubbed the project “Scéal Nua,” Irish for “new story.”

In selecting fellows, Street asked Irish playwrights Honor Molloy, Jaki McCarrick, and Deidre Kinahan to consider two main questions: Who would benefit from this? And who would be of benefit to others? The group they chose included writers from vastly different generations and life experiences. Three—Ciara Van Buren, Don Creedon, and Dubey—are originally from parts of Dublin. Summers hails from rural West Waterford in the South, and Leo McGann from Northern Ireland. The remaining three—Barbara Cassidy, Adin Lenahan, and Molly Kate Babos—are U.S. natives.

Each week last spring, the Scéal Nua group met around a table in a conference room at Irish Arts. Street adopted the format of a writers’ group, with everyone bringing new pages each week to be read aloud, followed by conversation about what the group heard.

Sitting with them, I was struck by the way the writers often speak about their work in terms of discovery. While everyone at Scéal Nua applied with a script in mind, it’s clear that they feel a lot of freedom and safety to experiment, to write without always knowing where the work is going, even to set aside the project they originally proposed to work on something else. As director of the program, Street seems to function like a director, working to create a space that gives her collaborators room to explore and play.

A group of writers reading one another’s pages can be a bit of a mixed bag. We’re not always the best performers. But here the group attacks one another’s work with the skill and enthusiasm of clear professionals. Babos, in fact, began acting professionally as a child. In watching multihyphenates like Lena Dunham and Issa Rae flourish, she saw the opportunity that creating her own material could provide.

“Everyone started to say, if you want it to get produced, you ought to write it yourself,” she said. Van Buren has performed in film and TV as well as plays. She came to New York primarily to audition, but a play she’d written landed her an artistic residency with the Barrow Group. Success there fed her interest. As she put it, “I got a bit of the bite to try to write more.”

Even those who haven’t acted in a while, like Cassidy—who said she started writing after she realized she was “going out on auditions for things where there wasn’t an interesting artistic idea for me”—show the kind of nimble playfulness any writer would hope for when hearing their material presented.

These writers’ subjects and forms are all over the map, with scenes set among high school teens in Dublin; at a community day center for children with intellectual disabilities; in a distant and dystopian future. Creedon’s scene about a pregnant woman dealing with the father of her baby had the group in stitches with its portrait of Irish family dynamics. McGann’s story, about an Irishman whose life is turned upside down when the American woman who had agreed to marry him so he can get a green card decides to blackmail him instead, likewise resonates deeply in present-day America.

Meanwhile, Adin Lenahan, who cites Christopher Durang as a major inspiration, is writing a dark play about a young incest survivor having visions of Winnie the Pooh possessed by Jesus. Pages of the main character talking to Winnie-Jesus had the room first roaring, then pin-drop silent. “I think a lot of religion is really cruel and perverted and unfair,” Lenahan said of their piece. “And I think that there are ways you can explore that trick the audience into suddenly thinking about their own relationship to religion and how it might be something in their lives that is a darker influence than a more positive one.”

As the group talked about one another’s scenes, responding to some basic prompts from Street—What did you hear? What did you like? What are your questions or things you’re confused by?—the wisdom of having a program like this dedicated to writers of the Irish diaspora became clear. The group’s shared experiences enable them to speak to each other’s ideas to a unique degree. A scene set in Ireland with a radio playing in the background, for instance, led into a conversation about how the radio is always on in Irish homes, how it’s almost like part of the family, which opened up new ideas for the writer. Watching a scene that featured an Irish bartender in New York, writers began to talk about the way Americans fawn over an Irish accent, particularly as spoken by men, which led to questions of how this character might use that “superpower” from time to time.

The three American-born members of Scéal Nua don’t share all of these experiences. “In a way, I feel a bit of a fake at times,” Cassidy confided. Yet those moments of disconnect have proven valuable, as well. “I like having to question my identity, being uncomfortable with myself,” Cassidy said. “I can put that into a character.”

Added Babos, “I wanted to explore what it meant to be part of the Irish diaspora, and part of being part of the Irish diaspora is that I won’t quite get all the references. It’s an interesting experience too. You get to sit back and listen and watch rather than needing to interject all the time.”

Lenahan has also found the fellows to be an especially meaningful audience for their work. “Sometimes you’re with people who just don’t get your approach or your sense of humor or your storytelling,” they said. “I have found that this group, I think because of their Irish backgrounds, have been able to relate to it and take it seriously.”

Much like the Irish Theatre of America dreamt of long ago, many of the Scéal Nua fellows’ stories speak to a contemporary Irish experience, as well as the unique relationship between Ireland and America. “I find the intersection between Ireland and America fascinating always,” McGann said. In a prior play, The Honey Trap, he told the story of an American oral history of the Irish Troubles (with the Washington Post raving about this “taut and twisty drama” that “shouts the talent” of McGann).

When Creedon left Ireland in the 1980s, “I honestly needed to get out of there,” he said. “And I never looked back, in some sense.” But even after living in the U.S. for many decades, writing dozens of plays and co-founding the local Poor Mouth Theatre Company, Creedon still finds that most of his work is in one way or another about Ireland. “Nicola said one week, ‘Sometimes I think I’m trying to write this ‘state of the nation’ play,’” he said of his colleague Dubey. “I totally identify with that.”

Dubey chimed in: “I’ve always felt a responsibility to tell important stories. I think the theatre is a place where people can have an experience that might make them think differently or question things.”

Said Summers, who grew up with American troops landing in Shannon en route to the Middle East, “The Americanization of Ireland was a big topic of conversation.” While his plays are always set in Ireland—“I can’t avoid it,” he admitted—the U.S. always looms large. “I think of Ireland like a green mirror for what’s happening here, or for what’s happening globally. There’s something really interesting about this post-colonial but patently neoliberal Ireland on the outskirts of Europe.”

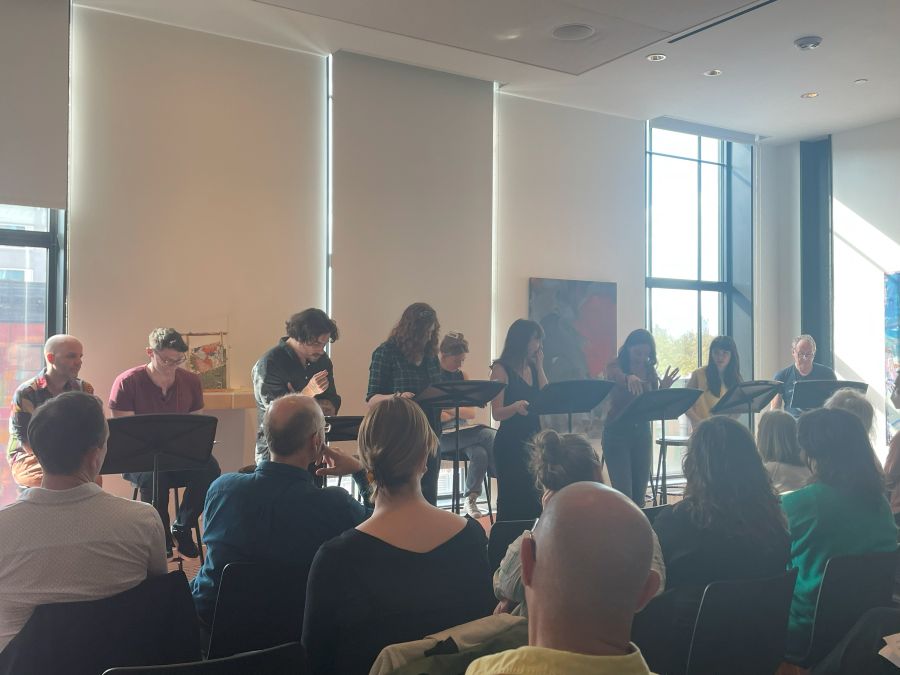

Last summer, Scéal Nua hosted a public reading of some of the material its writers have been working on. Sometimes readings like this bring in outside actors. Given the talents of this group, that wasn’t necessary. Sitting on stools before microphones, the writers introduced their material to a packed room, then let the group dig in.

The result was not only a celebration of their writing but an expression of the community that Street, Mellamphy, and their fellow writers have built. Unlike Mellamphy’s old bar, there is no sense in this room of artists throwing one last Hail Mary before a final farewell. Instead, there is the feeling of something quietly beginning and gaining in strength through the encouragement and support of one another. “Writing can be very isolating,” said Van Buren. “Having this sort of base and family to come back to every week is really special.”

While initially this first go-round of Scéal Nua was set to run through the spring readings, the group has continued to meet throughout the summer and fall. The group now plans a festival of full-length readings of plays by the Scéal Nua writers at the Irish Arts Center in late spring/early summer. “The goal is that we create and develop and work,” says Street. “I think if we do that consistently enough, and we don’t stop showing people the work and developing it together, at some point something’s going to happen. If you build it, they will come. I think that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Jim McDermott is a freelance writer in New York and runs TheaterWow, a newsletter dedicated to highlighting members of the theatre community whose work is often overlooked.