Outside al-Mujtahid Hospital in Damascus, families study gruesome printouts taped to the walls.

The pictures are of the bodies of prison victims, mangled from years of torture. Everyone in the crowd is searching for someone. Most leave without answers.

A young woman in a black ponytail walks away from the wall, shrieking.

“You knew about this. You always knew,” she yells. “You didn’t do anything about it.”

The crowd is silent. Then one man says, “God will have his justice after death.”

“What God?” she answers, storming away. “I don’t believe in God.”

Roughly 100,000 people are missing from Syria’s now defunct prison system, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, but locals believe that number is underestimated. We are told the most common cause of arrest under the fallen government of Bashar al-Assad was a real or perceived criticism of the regime.

On the streets of Damascus, every single person we meet is missing someone. And as more mass graves are discovered, hope is fading that more victims will be found alive.

At a crowded bakery, where families queue for about an hour for bread, outside a mosque where young people celebrate their new-found freedom, and on the streets near the hospital, where men and women weep openly, we ask the same question, loudly: “Does anyone here NOT know someone who has disappeared?”

“Every family in Damascus is missing someone,” says a man outside the bakery. At the mosque, one woman, Hiba al-Sadfy, says she is one of the lucky few who hasn’t lost anyone. But her husband was in jail for three years, and her nephew is still missing.

“I was sending food and medicine to Ghouta,” says her husband, Anas al-Nesmeh, 45, in the courtyard of the iconic Umayyad Mosque. Ghouta is a suburb of Damascus that supported the uprising against the Syrian government from its beginning in 2011. It was made famous in 2013 when the regime dropped chemical weapons on neighborhoods there, killing more than 1,400 people.

“They arrested the driver, and he told them I was sending it,” Nesmeh explains.

He then spent three years in a prison where inmates died from lack of food and medicine and torture was a regular part of life. Sadfy, his wife, points out marks still prominent on his wrists, where officers stubbed out their cigarettes.

“He still has lines on his back from whipping,” she adds.

Funeral

Around the corner from the hospital, there is a funeral for Mazen al-Hamada, a young man who died in prison after years of torture. Originally, Hamada was reportedly arrested for smuggling baby food into rebel areas. After his release, he moved to Europe where he became an international advocate for Syrian torture victims.

“The human brain can’t imagine it,” he says in a film widely circulated online where he describes gruesome beatings and sexual assaults. “Many people died under torture.”

A week ago, Hamada’s body was found in the hospital among other victims of the notorious Sednaya Prison.

Outside the funeral, one young man hugs his friend as he cries. He tells us he didn’t know Hamada, but his heart is too broken to say more. “I can’t stand this pain anymore,” he says. “I’m so sorry but I can’t talk.”

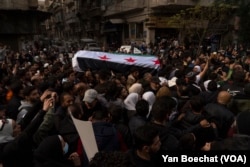

We follow the funeral procession as a growing crowd carries the coffin through the streets, draped in what was, less than two weeks ago, a rebel flag. Now it is the flag of Syria.

Soon it is as much a protest as a procession and the crowd chants familiar slogans like “The people of Syria are one!” and less common ones, like, “The people demand the execution of Bashar!”

Pictures of Assad, the former president who fled Syria as rebels swept through the country, have been torn off buildings or scratched out. A rubbed-out poster of Assad’s face is placed on the ground at the entrance of Damascus’ ancient market, so shoppers can stamp on it, or walk over it like it was nothing.

Another torn-up poster of Assad’s face hangs on the Ministry of Justice, now manned by a single bearded soldier, wearing a blue windbreaker under his camouflage jacket.

I ask him if he thinks the people who are demanding justice will get it.

“Sheik Abu Mohammed will provide justice, God willing,” he says, referring to Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, who is now called by his given name, Ahmed al-Sharaa. He is the leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the rebel group that led the militias as they took over Syria.

In less than two weeks, the rebels conquered lands held by the Assad-family dictators for half a century. We read in the news that HTS was blessed with a just cause and excellent timing. Russia and Iran were embroiled in other wars as Syrian rebels swept through the country. Nobody I know believes that this is the full story.

We leave the ministry guard and find the rowdy funeral/protest has moved on. A shopkeeper tells us he didn’t see where they went. We got a taxi to the cemetery where some locals say the burial was quick, and the people left.

We asked the driver to take us back to the hospital. As we pass through the next square, he tells us there is a prison under the road.

“How do you know?” I ask.

“I was taken there when I was nine years old,” he says. At the time, one of his friends stole something, but his memory is fuzzy, he adds. The prison was crowded, and he was beaten with a cable before his mother bailed him out.

“They butcher women and children,” he says. “Even if you mention Bashar’s name unintentionally, you may be arrested.”

Celebration

On the way back to our hotel, Umayyad Square is packed with revelers. Young men hang out of cars, waving Syria’s new flag and honk their horns. Children pose on a tank or with AK-47s for pictures. Sellars prepare banners and fireworks for the night’s festivities.

We find the remnants of a similar party in the main square in Aleppo the next day, but the crowds have dissipated. Many businesses have reopened but the currency is fluctuating so fast in Aleppo, shop owners say they don’t know how much to charge.

At the market outside the Aleppo Citadel, a thousands-of-years-old castle, young men sell cigarettes and coffee, while camel owners encourage people to purchase short rides. “Don’t be afraid of the camel!” one man calls as he leads his camel by a rope through the crowds.

We meet Imad al-Sawa, 20, who returned from Iraq only last week, selling coffee and cigarettes near the citadel. After three years abroad as a refugee, he came home the day after the rebels took Aleppo.

Sawa fled Syria at 17 years old, like so many other teenage boys, to avoid being forced to either join the military or go to jail. In Iraq he found hard work, deep poverty and no possibility for a better future.

“It was like I had no soul,” he says. “And now it is back.”