Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

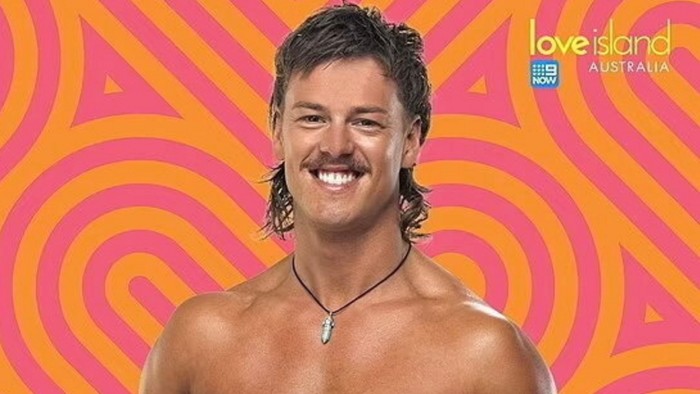

A stint on Love Island Australia could have set up Jordan Dowsett for a successful television career but, instead, he opted for a less glamorous though more lucrative job as an electrician in the outback.

A shortage of electricians means that those willing to endure long shifts and live on remote sites can potentially earn up to A$200,000 (US$124,000) a year — double the national average salary and not far off the average MP salary.

“It’s a cup half full/half empty life. You do 12-hour shifts, there’s the heat, the flies and you’re stuck in a donga [temporary housing] in a single bed. But you’re fed well and everything’s covered. You leave your credit card at home. You earn good money and you get plenty of time off,” said Dowsett of his life as a fly-in, fly-out electrician.

The high salaries reflect the fact that fewer Australians want to be electricians, creating a potentially devastating shortage as major renewable energy, mining and data centre projects come online.

Australia needs 32,000 more electricians by 2030 to meet the demand for workers, according to a report from the Clean Energy Council, citing government statistics.

But that figure is an underestimate, according to Michael Wright, national secretary of the Electrical Trades Union. If Australia is to make good on the government’s plan to become a “renewable superpower” and revive manufacturing, it needs about 42,500 more electricians by 2030 and 100,000 by 2050, he said.

“From the Tesla to the turbine, from the power point to the power plant, you will need sparkies,” Wright said. “That’s why this is so important.”

The shortage is a particular chokepoint as the country plots its transition from an economy reliant on coal and iron ore to one with renewable energy and advanced manufacturing at its core, said Roy Green, emeritus professor and special innovation adviser at the University of Technology Sydney.

“If we are to succeed in making this transition this economy needs to make, then we need to make sure all the pieces fit together,” he said.

The shortage of electricians stretches back to the early 1980s, said Wright, as more Australians opted to go to university rather than take up a trade. He said electricians often have “FBI” — fathers, brothers or in-laws — working in the sector.

That widening shortage has been papered over by migrants who are willing to “do a stint in the bush in very harsh conditions and hop on the first plane back to London”, said Wright. Almost 400 electricians were granted temporary visas in 2024, the highest level in eight years, according to government migration data.

“It’s only going to get harder,” he said, describing the hope that skilled immigration would continue to bail out the country’s electrician shortage as a “chimera”.

Some companies are searching for solutions. AirTrunk, the data centre company acquired by Blackstone in 2024, launched a programme in May to take on 30 electrical and mechanical apprentices across its Australian operations. “There is a shortage of these crucial workers who maintain and operate critical hardware,” said Matthew Ward, AirTrunk’s associate vice-president of operations advancement.

The Australian government has also invested in vocational training to bring more workers into the system. Yet the electricians’ union said there was also a shortage of teachers, particularly in fields such as renewable energy, and that holding on to young workers was difficult in a tight labour market. Two out of five apprentices drop out before completing their qualification, the union said.

Warren Bain, an electrician in Melbourne, said some large companies treat apprentices as “cheap labour” and that this deters many from joining the industry full time.

Not everyone can live the fly-in, fly-out life because of family commitments, Bain said. Others are drawn away from lower-paid electrical work into less demanding trades.

“Why smash around on the tools all day when you can just stand there and make more money,” he asked.

Dowsett described a clear age gap on outback sites, which are dominated by hard-working older sparkies and skilled immigrants. The fly-in, fly-out routine can “set you up for life”, but few of his peers are willing to make the sacrifice, he said.

“They prefer the lifestyle of working in cafés.”