Jasmine Chen has been married for two years, but the idea of having children is not part of her plans. The 28-year-old bank teller who lives in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou said raising children in China is just too expensive.

“Even though anyone can raise children, regardless of their economic situation, I would want to make sure that I could give my children the best possible life if I decide to get pregnant, but that’s not what I think I could achieve,” she told VOA in a written response.

Chen is among a growing number of young Chinese women who have decided not to have children despite a growing number of government policy measures, including subsidies and other incentives, aimed at boosting births.

Last year, new births in China fell by 5.7%. That’s a record low of 6.39 births per 1,000. In contrast, the mortality rate was 7.87 per 1,000 people.

The decline has led to the closure of more than 14,000 kindergartens across China according to China’s Ministry of Education. Statistics also show more than an 11% drop in preschool enrollments, and kindergarten enrollments experienced a 10.30% decrease.

‘Fertility friendly’ policies

To boost the country’s declining birth rate, China’s State Council, the country’s chief administrative authority, rolled out a policy with 13 directives aimed at enhancing “childbirth support services, expand childcare systems, strengthen support in education, housing, and employment, and foster a birth-friendly social atmosphere.”

The new measures also include providing maternity insurance to rural migrant workers and people with flexible employment, as long as they have basic health insurance. The policy document also urges local authorities to implement parental leave.

Other measures include offering subsidies and medical resources for children and the call on local governments to budget for childcare centers and preferential taxes or fees for these services. Local authorities are also encouraged “to raise the limits of” housing loans to help families with multiple children buy homes.

Despite the Chinese government’s efforts, analysts say these new measures may only have a limited impact on boosting China’s birth rate.

“China is currently facing a serious debt crisis, many local governments, especially those in northeastern or western provinces, won’t have enough financial resources to implement the policy directives that the state council has laid out,” Yi Fuxian, a demographer and expert on Chinese population trends at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told VOA by phone.

Fertility rates in Asia

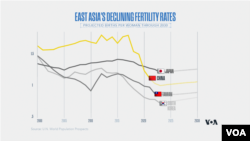

China is not the only economy in the region that is struggling with low fertility rates. According to economists, a rate of 2.1 children per woman is needed to sustain a population over time.

South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Japan have been struggling for years to raise their number of births. Yi said since Japan and Taiwan have already implemented similar measures with little success, it will be hard for the Chinese government to achieve its birth goals by rolling out these policy directives.

“Japan put so many resources into these policies, but its birth rate didn’t increase as a result, and the Chinese government may not have enough financial resources to replicate Japan’s policies,” he told VOA.

One child policy

Unlike most countries though, China had a stringent one-child policy for decades. That policy formally ended in 2016 when couples were allowed to have two children. However, the change in policy has done little to turn the trend around.

In addition to financial challenges, Yi said China’s persistently low birth rate is also the result of less willingness to have children and the growing prevalence of infertility among Chinese women, in part due to trying to have a child later in life, according to researchers.

“The one-child policy has changed the concept of childbearing for several generations in China, resulting in the lack of willingness to have children among the younger generation in China,” Yi told VOA.

Some young Chinese women told VOA that they worry once they have children, they would have to make a lot of compromises in their lives, including giving up the freedom to decide how to live their lives.

“Having a child and being responsible for it would make me lose the ability to leave for a trip whenever I want to and lose the very free lifestyle that I currently have,” Chen in Guangzhou said.

Others said they are terrified of the responsibility that comes with having children.

“I’m relatively healthy. My financial situation is manageable, and my parents even agree to help me out if I ever decide to have children. But I simply don’t want to take on the responsibility that I can’t get rid of once I have children,” Catherine Wang, a 33-year-old woman living in Beijing, told VOA in a written response.

Putting off marriage

In addition to the unwillingness among some Chinese women to have children, more Chinese people are getting married much later in their lives.

According to China’s official 2020 data, Chinese men’s average age for a first marriage was 29.38 while Chinese women’s average age for a first marriage was 27.95. Yi estimates that both numbers are probably now beyond 30 years old.

“Many people won’t be able to have children if they are delaying their marriage age and the Chinese government has done nothing to address this issue,” Yi told VOA.

Data released by China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs on November 1 showed a drop in marriage registrations for the first nine months of 2024. It’s a year-on-year decrease of 943,000.

Working overtime

Long working hours and low wages for certain people, such as factory workers, will make it hard for them to raise children, said some labor rights groups.

“In China’s manufacturing factories, workers frequently endure long shifts, typically from 8 AM to 8 PM, with only two days off per month, [and] the combination of low minimum wages and extended overtime working hours has resulted in numerous workers clocking over 300 hours per month,” wrote the editors of the China Labour Bulletin, or CLB, on the organization’s website.

A CLB spokesperson told VOA in a written response that unless Chinese workers have support from extended families, it will be difficult for them to raise children.

According to Chen, overtime work has been routine for her, and she does not think she can have enough time to childcare if she ever has children.

“Some people may seek help from nannies or older family members, but I think one thing that can’t be absent from children’s upbringing is quality time with their parents, and since my work is too busy, I don’t think I can fulfill that,” she told VOA.