On the Shelf

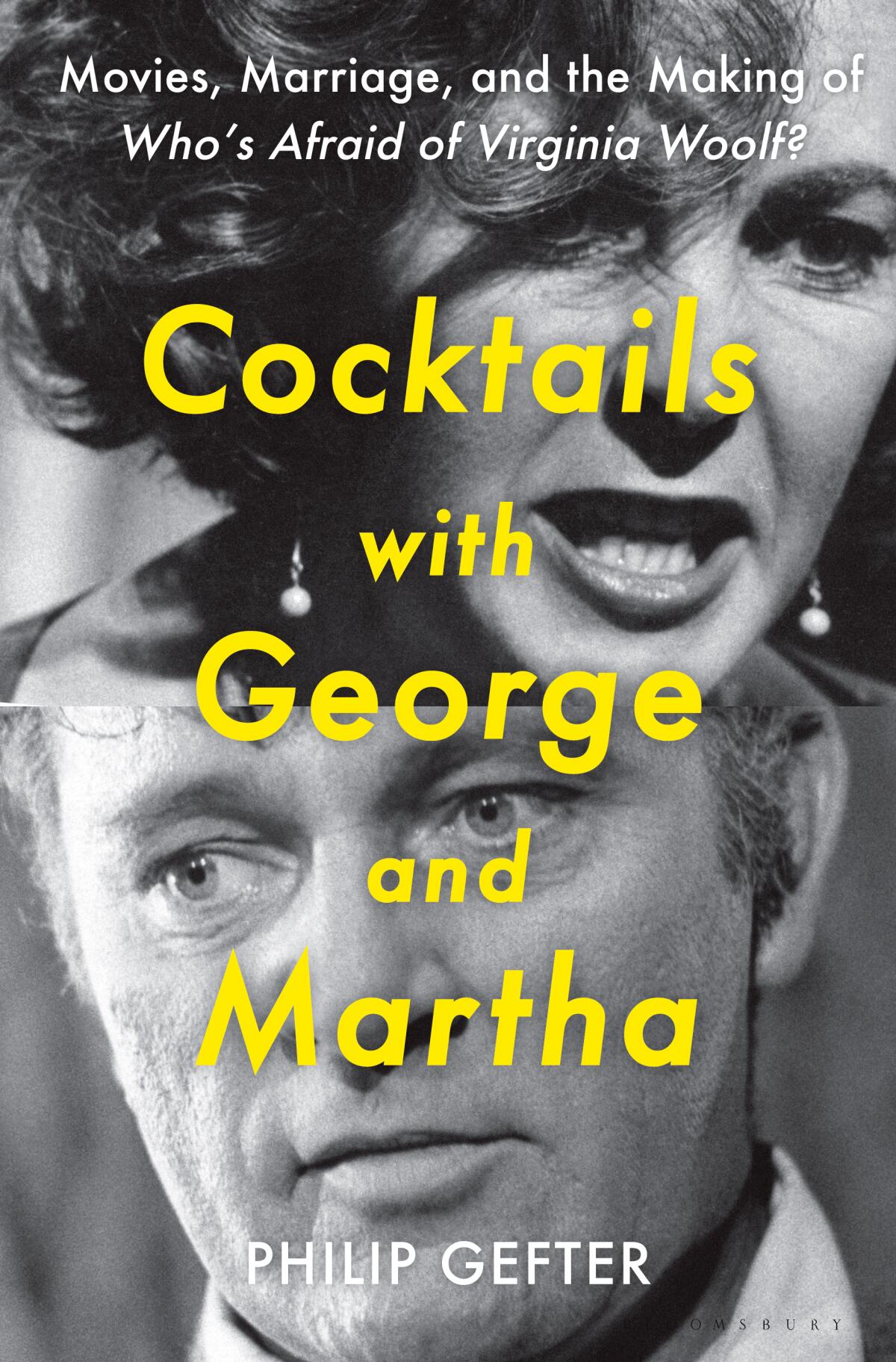

Cocktails With George and Martha: Movies, Marriage, and the Making of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’

By Philip Gefter

Bloomsbury: 368 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” the 1966 movie based on Edward Albee’s incendiary play, a middle-aged married couple turns a late-night gathering for drinks at their home into a game of full-contact mixed doubles. Played by mega-famous real-life spouses Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, George, a henpecked history professor, and Martha, the daughter of the college president, trade savage verbal barbs and sadistic pleasures as they enmesh a young biology professor (George Segal) and his mousy wife (Sandy Dennis) in their long, drunken, profane night of the soul. The directorial debut of Mike Nichols, and the winner of five Oscars (including Taylor and Dennis), “Virginia Woolf” is a portrait of matrimony as existential torment.

Philip Gefter, the author of the new book “Cocktails With George and Martha,” calls it “the truest portrait of love in marriage that I know.”

Come again?

“It was the first time a marriage was depicted with the kind of honesty in which the marriage itself was the subject matter,” Gefter said in a recent video interview. “Whether George and Martha’s marriage is good or bad is not the point. The point is that, to my mind, it’s an anatomy of marriage itself. It’s almost like an X-ray of what occurs beneath the surface of every marriage. And I think that’s another reason it’s such a poignant film.”

Philip Gefter, author of the new book “Cocktails With George and Martha,” calls “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” “the truest portrait of love in marriage that I know.”

(Bill Jacobson)

Gefter’s book — subtitled “Movies, Marriage, and the Making of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’” — has a great many characters and subjects. There’s Albee, the playwright who pushed the boundaries of acceptable Broadway content when “Virginia Woolf” premiered onstage in 1962 and who became the target of homophobic venom from pundits who accused him of degrading Western civilization and, yes, the institution of marriage. (Albee, who was gay, flatly rejected conjecture that his play was a veiled portrayal of a gay couple.) It’s about Nichols, the Broadway wunderkind and collector of celebrity friends eager to make his mark in Hollywood, and Ernest Lehman, the producer-screenwriter who tangled with Nichols regularly. And it’s definitely about Taylor and Burton, who created a scandal when they fell in love on the set of “Cleopatra” and kicked their respective spouses to the curb.

But the central theme is what it means to live as husband and wife, and how “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” kicked down the doors of previous and comparatively staid cultural depictions of marriage. As Gefter writes, “George and Martha go at each other with blatant vulgarity and vicious accusation. Their hatred tangles with love, their rage follows on the heels of affection — a protracted, if extreme, version of all marital discord, for better or worse.” Or, til death do us part. The casting of Taylor and Burton, who could squabble with the best of them (and who married and divorced each other twice), only adds to the frisson.

Even as he portrays the film and play as archetypal, Gefter, a longtime photography critic and author of a biography of Richard Avedon, also pinpoints the married couple that likely served as the inspiration for George and Martha. Albee was friends with Willard Maas, a poet and experimental filmmaker, and Marie Menken, a “painter-cum-filmmaker,” who hosted cultural luminaries including Richard Wright and Arthur Miller at their Brooklyn Heights apartment, where they also engaged in epic, drunken arguments. Andy Warhol made a film, “Bitch,” which was recently restored, showcasing the Maas and Menken show. As Menken is quoted in the book, Albee “used to come here every time to eat and just sit and listen while Willard and I argued. Then he wrote ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’”

But Menken and Maas would have been hard-pressed to surpass the rapier wit of George and Martha. Here’s George, when his wife emerges in a way-too-tight outfit (Taylor gained weight to play a character 15 years older than she was): “Why, Martha! Your Sunday chapel dress!” And Martha, fed up with her husband’s barbs: “I swear, if you existed, I’d divorce you.” Rewatching “Virginia Woolf,” one is struck by how flat-out funny the carnage gets. Albee certainly knew. As Gefter writes, during the initial Broadway run, starring Uta Hagen and Arthur Hill, the playwright kept having to sidle up to director Alan Schneider to remind him of the material’s inherent humor: “Funny. Humor. Funny.”

“The dialogue is brilliant and hilarious,” Gefter says. “One minute you’re laughing out loud, and the next minute you’re gasping at what they’re actually saying to each other and doing to each other. That combination is really important in terms of why the movie is so successful.”

As Gefter writes, “Virginia Woolf” arrived at a moment when cultural depictions of marriage tended to look like TV’s “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet,” which ran from 1952 to 1966, or “Leave It to Beaver” (1957-63). But change was afoot. “Revolutionary Road,” Richard Yates’ novel about a toxic, suffocating marriage in the Connecticut suburbs, was published in 1961. Around the corner was Ingmar Bergman’s “Scenes From a Marriage” (1973), a groundbreaking Swedish TV miniseries, adapted into a movie in 1974, that dissects a flailing marriage and inevitable divorce in excruciating (and riveting) detail. It makes a fair amount of sense that Bergman also directed the first Swedish stage production of “Virginia Woolf.”

For Gefter, the fierceness with which George and Martha spar, and the fact that they remain a team, is a reflection of their flawed but undying love. It also makes them — shudder to think — representative. “Though their love is genuine,” he writes, “their marriage is imperfect and, in that sense, typical of all marriages.” That’s an idea to keep in mind, and perhaps provide succor, during your next marital showdown.