Back in August the 29-year-old country singer Shaboozey gave the packed audience at the Grammy Museum some advice for staying healthy on the road.

Whenever he plays his smash hit “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” which has topped the Hot 100 for seven weeks and counting, he swigs from a bottle of Jack Daniel’s. The two have “got a history,” he touts in the song’s chorus.

But after one especially raucous show, Shaboozey recalled a manager taking him aside backstage. “They said, ‘You know you can put iced tea in there instead,’ ” the singer said and laughed.

Later that night, when he performed the song twice in a row, he indeed pulled a bottle of of Jack for the big moment. Who knows what was actually in there, but if it was whiskey, Shaboozey definitely deserved a real shot.

The singer-songwriter, a Virginia-raised child of Nigerian-American parents, has become the breakout country artist of the year, appearing on Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter” and dominating charts with “A Bar Song (Tipsy).” His single has ruled the generalist Hot 100 and country radio alike — a feat not even Beyoncé pulled off. His LP “Where I’ve Been, Isn’t Where I’m Going” belongs on any list of the year’s most important country records.

Shaboozey’s been embraced by country’s establishment, but as a young Black man in America’s most conservative music format, he’s under no illusions about it. His songwriting is bracing and melancholy in ways “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” barely suggests. After his raucous ascent on the back of a huge hit, will country fans stay for the real thing?

“I’ve been going to Stagecoach for years, walking through there when nobody knows who you are, and you’re one of very few people of color at that whole festival,” he said. “Who would have known, like, two years later that same dude is playing to 60,000 people screaming.”

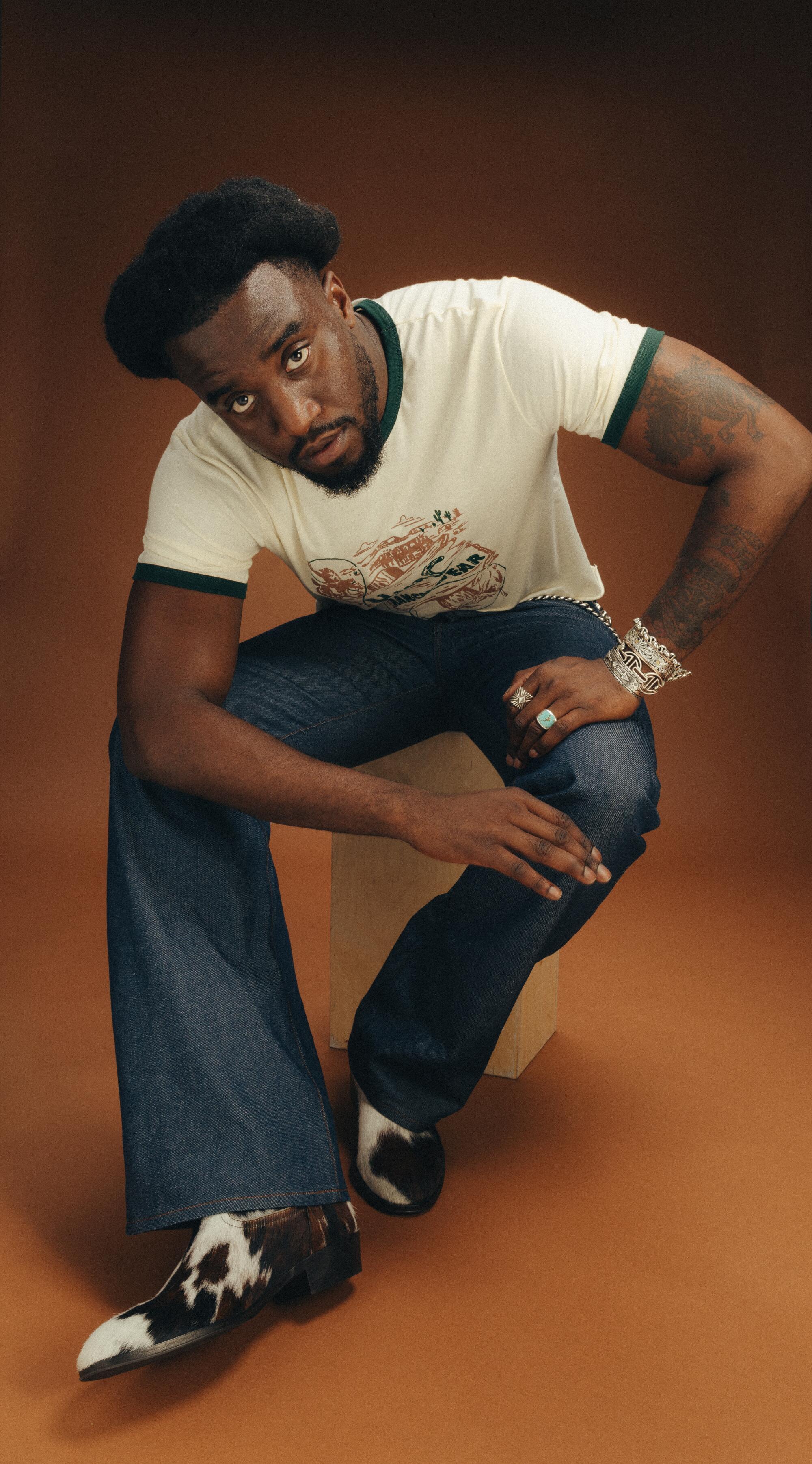

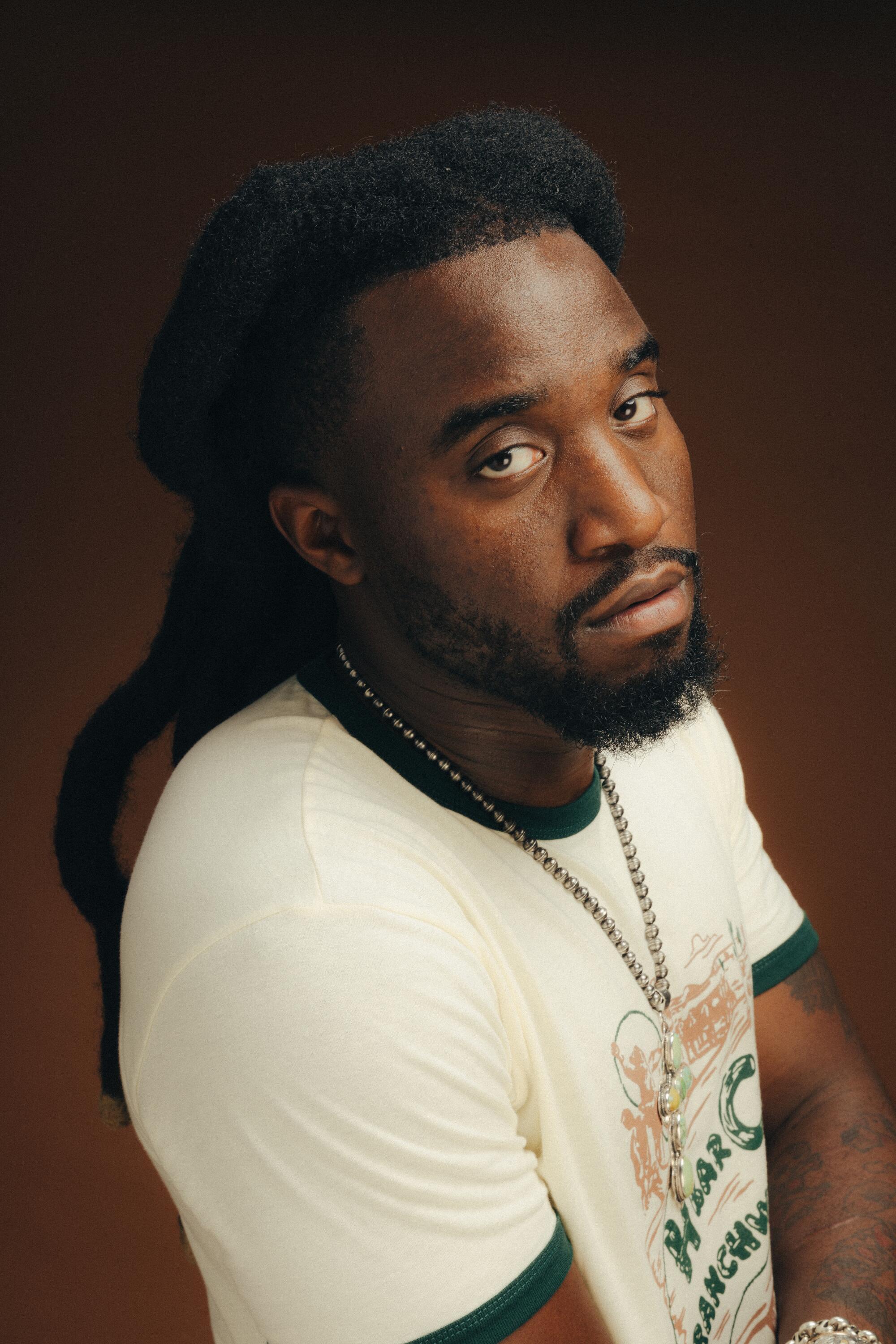

On a blazing afternoon at a Culver City photo studio, Shaboozey arrives a little frazzled, after a meeting with a vocal doctor to get in the best possible shape for his upcoming headline tour, where he’ll play major theaters like the Fonda. Born Collins Chibueze, his artist name is a riff on a nickname, given by a high school football coach who failed at spelling his name right.

In person, he’s tall and commanding, still with the muscular frame of a young athlete, but also the soft-spoken baritone of someone who’s worked out a lot of complicated feelings in his songwriting.

“I think there’s the folk tales, the storytelling aspect that you see in Western African music that’s also a very big part of country music,” Shaboozey said.

(Ethan Benavidez / For The Times)

That day, “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” was still in the saddle atop the Hot 100 and the country airplay charts, making Shaboozey arguably the buzziest singer in the most influential genre in America right now.

The single is diabolically perfect in its craft. It discreetly calls back to J-Kwon’s 2004 hit “Tipsy,” an elder-millennial college-party staple, but does so less as a straight cover than by using the song as a reference point for nostalgia and longing for release. (It’s a classic-country songwriting move; a similar trick drives Cole Swindell’s “She Had Me at Heads Carolina”).

The chorus is boisterously chantable on a big night out, but its lyrics are flintier than you think (“Gasoline and groceries, the list goes on and on / This 9 to 5 ain’t workin’, why the hell do I work so hard?”).

Country and rap, historically pitted against each other, have always been cousins, whose sounds have intertwined closely over recent years. Shaboozey understood both as a common reference point for younger country fans, using that sweaty party anthem for a sly twist on the drinking-song tradition.

“It’s just a staple of country music, the drinking song,” Shaboozey said. “But I knew the world was looking for something unique. Y2K is coming back, everyone’s playing 2000’s music already, and ‘Tipsy” was a big party song. So you fill it up a little bit, this equation, just in time for summer. I feel like we ticked all the boxes, but we put a lot of work in to be ready for a moment like that.”

That moment paid off across formats, topping country airplay charts when like-minded songs by Lil Nas X (“Old Town Road”) and Beyoncé (“Texas Hold ‘Em”) never came close.

This wasn’t an obvious outcome, to say the least. Shaboozey began his music career more overtly rap-aligned, even as his breakthrough single “Jeff Gordon” was named for the NASCAR driver. He released his debut LP, “Lady Wrangler,” on Republic in 2018. He’d moved to L.A. that year with a record deal and a bit of cash floated from his mother to pursue his dreams, but he didn’t find much community for his country-crossover sound. “There’s like [Hollywood bar] Desert 5 Spot and that’s about it,” he said and laughed. “L.A.’s not really a hub for that. It’s hard trying to find those spaces here. I hope more open up.”

His sound inched closer to country instrumentation, like on 2022’s “Why Can’t Cowboys Cry?” off “Cowboys Live Forever, Outlaws Never Die” on the indie Empire, though nothing hit the Hot 100 or country charts. But the industry took notice behind the scenes. He was driving a friend’s borrowed car around West Hollywood when he got the call that changed his life: Beyoncé wanted him in the studio for a concept album drawing on the Black roots of country music, and the outlaw place that Black people carved out in a country that can still hate and fear them.

Shaboozey brought a regal, trap-infused croon to the banger “Spaghettii,” and a nimble R&B run to “Sweet Honey Buckiin’,” each highlights of an album bearing witness to a Black culture intertwined with American cowboy archetypes.

“It felt like I was where I was meant to be,” he said. “You’re not brought there to be nervous. You’re there to do what you do best.”

Shaboozey performs at Outside Lands music festival on Aug. 9 in San Francisco.

(Amy Harris / Invision / AP)

Shaboozey admired Bey for taking the risk to make a country-inspired album with no guarantee of being embraced by Nashville (its reaction to her barnstorming 2016 CMA performance with the Chicks was mixed, to say the least).

“We’re aligned on seeing the mirrors between hip-hop and country, and being Black and being an outlaw,” Shaboozey said. “Having to protect yourself, being forced to band together to survive.”

Shaboozey’s own upbringing was typically American in some ways — a childhood in the slow town of Woodbridge, Va., just south of Washington D.C., fascinated by his own state’s robust hip-hop tradition (he admires Pharrell Williams’ fearlessness across genres) and the country music his Nigerian dad grew to love here.

He found deeper connections between the West African culture of his parents, and the Americana they adopted.

“I think there’s the folk tales, the storytelling aspect that you see in Western African music that’s also a very big part of country music,” he said. “Obviously the banjo’s got African roots too. Country music came from people in the South and Appalachia, slaves and indentured servants from Europe, each gathering and trading stories.”

The exchange goes both ways. Videos of African weddings where crowds line danced to songs like Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler” surprised and delighted Western social media. Singers like Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family have inspired African singers like George Sibanda, and the Nigerian singer Joe Nez loved classic country singers like the ‘50s American star Jim Reeves.

“There’s a lot of Nigerian people that are like, ‘Yeah, my dad did play a lot of Don Williams,’ ” Shaboozey said. “Certain artists every generation cross that water. It’s interesting to see Nigerians’ and immigrants’ relationship to American music, especially when they’re living in the South, just trying to live an honest life working and building that home.”

Shaboozey has built a formidable career to becoming one of the hottest artists of 2024. But his writing is much thornier on “Where I’ve Been, Isn’t Where I’m Going,” with contemporary worries about drugs, loneliness and authenticity.

A song like “Highway” spins a very American image — being crushed in a car crash — to explore his own own mistakes in a relationship. “Got Jesus on the hotline sayin’ ‘You need help.’ / Put the liquor on the shelf, tell the devil, ‘Farewell,’ ” he sings. “I might die on the highway with all my regrets.”

On “My Fault,” he duets with Noah Cyrus on a ballad of co-dependency in a bleak L.A., a dark mirror of Soundcloud rap’s obsession with benzos and nihilism — “It’s hard for me to see you when you’re drunk / In a bathroom stall, takin’ pills, givin’ up … This road you lead me down is too long / It ain’t nothin’ like the streets I grew up on.”

“I wrote it about a relationship I had with someone who was abusing substances. It was hard to kind of see somebody just self-destruct like that,” Shaboozey said. “It is really easy to slip into those things here, those low vibrations. I think that’s why those songs really speak to me.”

But when Shaboozey raps (more or less) on “Drink Don’t Need No Mix,” he finds the threads between Texas hip-hop duo UGK’s candy paint cars with wood-grain steering wheels and Nashville’s “bachelorettes on Broadway and they all wanna be my wife.”

“A Bar Song (Tipsy)” is his calling card for country radio, and his LP landed just behind Morgan Wallen’s on the country albums chart when it debuted in May. The album is rich with connections between all corners of Black and Southern Americana. Will the Nashville establishment welcome the full picture?

“Especially after Beyoncé, his sound is pushing the country format in a direction that’s very timely right now,” said Amanda Marie Martínez, a historian at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill who studies the intersection of race and country music.

Black acts like The War and Treaty and Mickey Guyton have won critical acclaim, but “country radio still dictates business practices and its gatekeepers wield power,” Martínez continued. “If you look back from Charley Pride to Darius Rucker to Kane Brown, Nashville usually only allows one Black man to succeed at a time, and that’s troubling. There’s never been a Black woman with sustained commercial success on country radio. It’s not a nice reality, but the only template is to not talk about anything controversial with regards to being a Black man in country.”

“A Bar Song (Tipsy)” is Shaboozey’s calling card for country radio, and his LP landed just behind Morgan Wallen’s on the country albums chart when it debuted in May.

(Ethan Benavidez / For The Times)

For his part, Shaboozey said the Nashville establishment has been open to his vision, especially as the genre embraced artists like Jelly Roll and Post Malone, who came out of hip-hop.

“When I went over there, I think it’s just a lot of people just trying to write good music,” he said. “They were super supportive. You create those relationships and you treat people the way you want to be treated, and when they see it, they’re like, ‘Man, we believe in him.’ Good music connects with people. I hope that the success of my song didn’t happen because they felt they needed diversification.”

For now, at least, Shaboozey rules all formats of radio and streaming, and he could be a formidable force at next year’s Grammys, where a young artist updating old traditions with phenomenal commercial success would be poised to do well. This fall, he’ll hit the road for his first major headline tour, which hits the Fonda on Oct. 14-15.

Celebrity doesn’t come easy to him, though.

“The past six months have just been a complete 180, honestly,” he said. “Coming from a small town, you don’t really think, ‘I’m gonna be this person that people recognize around the world.’ Sometimes I can’t go to certain places. It’s hard for me to come to grips with a lot of people being familiar with me.”

A new lawsuit filed by his old record label Kreshendo Entertainment, claiming breach of contract, may complicate his ascent. His songs allude to anxiety about his success — “Break the rules, cross a line, make a mess / This could be the only chance that you get,” he sings on “Let It Burn.” The album closes on “Finally Over,” where he candidly admits that he’s “Starin’ down the whiskey, longin’ to be sober / All my friends have got careers, and mine just might be over / If I don’t sell my soul again, for another viral moment.”

Yet even as he writes about his fears that this commercial peak won’t last, some of his favorite artists are lining up to tell him it’s real, and deserved.

“The thing about the vulnerability that’s happening in music right now is that you’ve got to write honestly if you want to connect with people,” he said. “Noah Kahan told me that he heard that line in ‘Finally Over’ and was like, ‘Man, that hit me too.’ ”