NOGALES, Arizona — When Arturo Garino was mayor of Nogales, he joined fellow border mayors to campaign for national Democratic candidates, including then-President Barack Obama.

Now out of public office and with Arizona becoming an immigration hot spot, he told NBC News that he’s certain he won’t be campaigning for President Joe Biden. Though he voted for him in 2020, he said in an interview last month, he doesn’t know how he’ll vote this November.

“I don’t think what this administration is doing it right — letting all these people just come across,” Garino told NBC News. “I’m a Democrat, and I’m pretty pissed off.”

President Biden’s executive order signed Tuesday, dramatically restricting access to asylum for migrants at the border, shows just how vexing immigration is for his campaign, even among Latino voters who have generally sided with his party on the issue.

Voters like Garino, who once chastised the administration for continuing a pandemic ban on border crossings, are frustrated over the high number of migrant arrivals in recent years. At the same time, many blame Biden for a failure to deliver on promises for immigration reform for long-settled immigrants without legal status, despite years of blockades to legalization by Republicans in Congress.

In a presidential race with razor-thin margins, any erosion of Latino support in such a heavily Latino battleground state could be consequential.

A shrinking advantage?

As has historically been the case, immigration is not the top voting issue for Latinos in this election. But many Latino voters have used immigration as a litmus test, judging those to be anti-immigrant to also be anti-Latino, said Carlos Odio, a co-founder of Equis Research, a Democrat-leaning Latino polling and research company.

“That has changed somewhat in the last few years. The Democrats no longer have the advantage they used to,” he said. There are perceptions that Democrats have broken campaign promises to provide pathways to legal status for immigrants, and that Republicans aren’t going to go as far as they say they will with immigration crackdowns, Odio said.

Recent polls have shown a rise in Latinos agreeing with GOP calls for more border control, as well as increases in the percentage of Latinos who say Republicans and presumptive presidential nominee Donald Trump could do a better job controlling the border.

According to the latest NBC News survey, U.S. voters ranked immigration and the border a close second to inflation and cost of living as the most important issue facing the country. Less than 30% approved of Biden’s handling of immigration and the border. Republicans were far more likely, 42%, than Democrats, 4%, and independents, 15%, to see immigration and the border as a top issue, the poll showed.

An April poll from Axios-Ipsos and Noticias Telemundo found some hard-line positions on immigration have grown in popularity among Latinos. Building a wall or fence on the border, for example, jumped from 30% to 42% approval among Latinos between December 2021 and March 2024. But Latinos still are less likely than white Americans to support building a wall or calling for deportations, according to a Pew Research Center poll.

The Axios-Ipsos and Noticias Telemundo poll also showed that 64% of adult Latinos polled supported giving the president authority to shut down U.S. borders if too many immigrants are trying to enter the country. But also, 59% support allowing refugees fleeing crime and violence in Latin America to claim asylum in the U.S.

Clarissa Martinez de Castro, vice president of Latino Vote Initiative at UnidosUS, the country’s largest Latino advocacy group, said in a recent interview that the Biden administration and campaign have not been offering Latino swing voters a convincing counter-narrative to Republican talking points on immigration.

“It’s political malpractice. They’re ceding the space and allowing people with a different view to define them,” said Martinez de Castro, whose group recently endorsed Biden in Arizona.

Biden’s executive order is the latest in the administration’s offensive on immigration. Biden has been attacking Trump for essentially killing a bipartisan bill that included money for border enforcement, added visas and green cards for some immigrants and tightened asylum laws. After Republicans twice blocked that bill, Biden used his executive power to order the asylum controls.

More control, but no to crackdowns

Along with other liberal pollsters, Martinez de Castro cautioned against overstating the extent of changes in Latino voters’ views on immigration — or drawing the wrong conclusions from it.

It’s a mistake to assume that Latino voters’ unhappiness with the situation at the border means they want harsh, Trump-style crackdowns, she said. Her organization’s polling shows there is still strong support among Latinos for providing asylum to new migrants, Martinez said.

“All things being equal, immigration tended to be an area that favored Democrats, and still right now, Latino voters see more alignment (on immigration) with Democrats than what they see with Republicans,” Martinez said. “But it used to be a very high contrast, and that contrast is not as high as it used to be.”

This isn’t the first time immigration has been a thorn in the Democrats’ side. Former President Barack Obama was labeled “deporter in chief” in his first term for the high number of deportations executed by his administration. But then Republicans attacked him during his re-election campaign for failing to keep a promise to sign an immigration reform bill in his first 100 days in office.

In recent years, Republicans have blocked repeated attempts to pass comprehensive immigration reform. For years, the model for such failed legislative proposals involved providing a chance to earn permanent legal status to undocumented immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for decades, coupled with building up border security and other restrictive measures.

In Arizona, Republican legislators voted to put on the November ballot a proposal to empower local and state authorities to arrest and deport people they suspect of being in the country illegally — a realm of the law that is currently limited to the federal government.

Opponents have dubbed the new proposals “SB1070 2.0,” a reference to the “Show me your papers” law signed by Republican Gov. Jan Brewer in 2010 that allowed police to check the immigration status of people they stopped if they have a “reasonable suspicion they may be illegally in the country.” The widespread backlash among Latinos to SB1070 is often credited with turning Arizona from a reliably red state into the purple one it is today.

Migration changes and voter backlash

At a recent campaign event in Nogales for Kari Lake (the Trump-aligned Senate candidate), Yvette Serino, chairwoman of Latinos for Lake, said she has succeeded in converting some friends and family members to the MAGA cause. Serino herself comes from a prominent Democratic political family in Nogales, where her grandfather spent decades in public office.

“It’s very blue down here, very blue,” Serino said, but according to her, “a lot of people are switching.”

Like many right-wing Latinos, Serino believes the Republican Party under Trump has successfully tapped into religious conservative values prevalent among Mexican Americans — “God, family, country.” And on immigration, she said, Trump’s rhetoric increasingly appeals to Mexican American families who immigrated to the U.S. without illegally crossing the border or overstaying a visa.

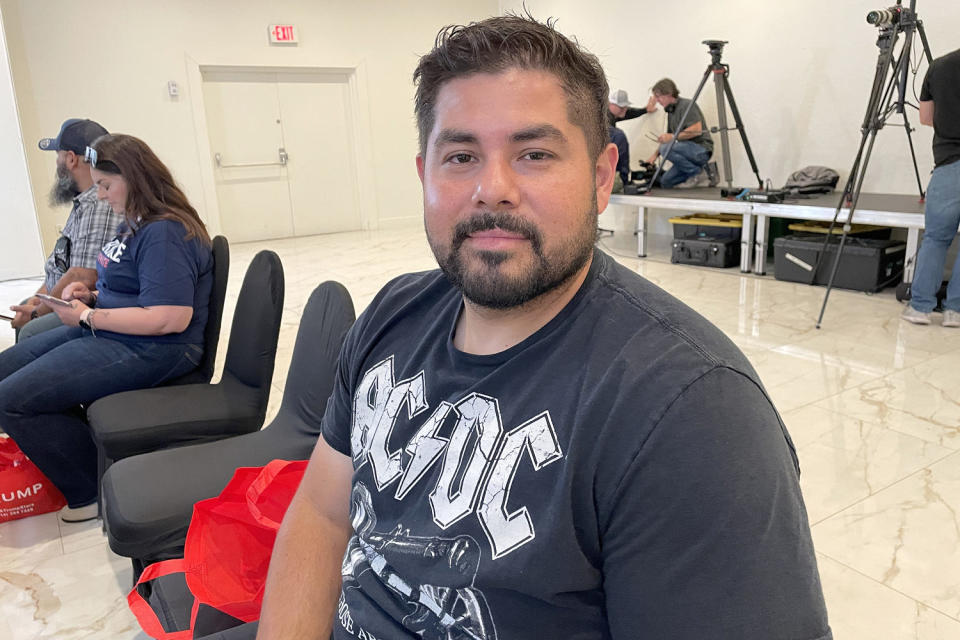

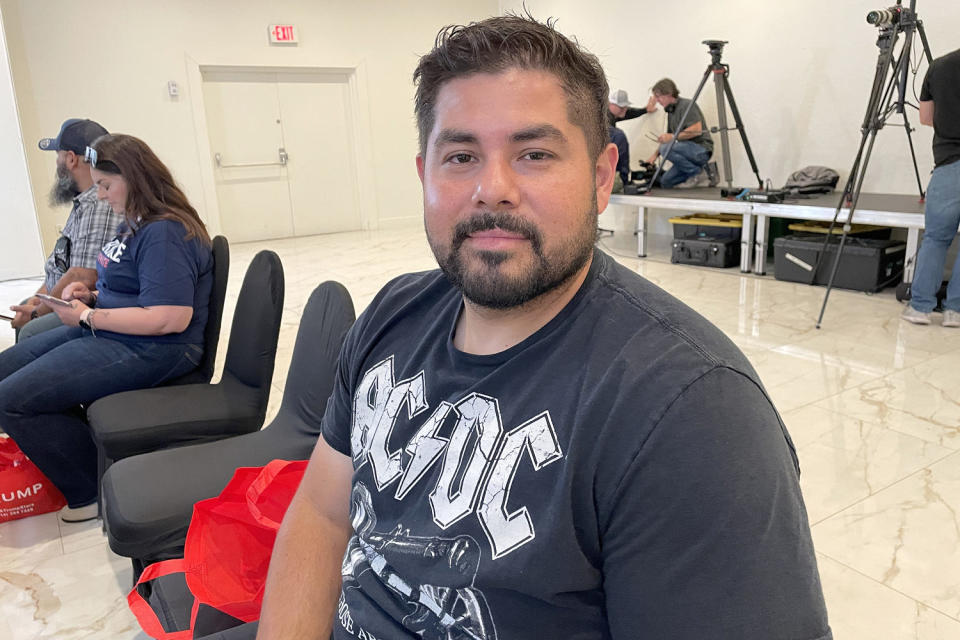

“I get it, people want to come and better their lives,” said Sergio Watson, a 35-year-old owner of a small trucking company who attended the Kari Lake event. “But I also think they should do it the right way, and I see a lot of people who just want a handout.”

Watson was born in Sinaloa, Mexico, before his parents moved their family legally to the U.S. Like most Latinos, Watson cites the economy as his top motivating issue as a voter — but he says the border is not far behind.

He said he voted for Hilary Clinton in 2016, but then voted for Trump in 2020.

“I used to follow [Democrats] because I thought they were for Hispanics, but they’re not,” he said.

Most undocumented immigrants in the Southwest crossed the border during an era of mass migration that began in the 1980s, when they were drawn to cross the border in search of jobs as U.S. employers increasingly relied on their labor regardless of their immigration status. The vast majority came from Mexico, and most evaded detection by the Border Patrol upon entering the country.

That sets them apart from today’s migrants, who mostly surrender to authorities and begin legal applications for asylum — a process that grants a sort of temporary quasi-legal status that includes a work permit after six months in the U.S.

Petra Falcon, founder of Promise Arizona and longtime immigration and community activist in Phoenix, said this has fueled some resentment among families of undocumented people who have lived and worked in low-wage jobs in the U.S. for decades with little relief from the federal government.

“The feeling is, ‘OK, well what about us?’” Falcon said.

About 5% of Arizona’s 2.8 million households are so-called “mixed status” families, meaning they include at least one person without legal status.

Luis Reyes, an Arizona State University student, is a member of one of those families. A Biden supporter, he acknowledged some immigrants — particularly those here for years without legal status, who still struggle and take risks to work and remain in the U.S.— feel competitive with migrant newcomers.

But he said many undocumented people have been in the U.S. across multiple administrations. “You can’t blame him [Biden] for people who got here 20 years ago,” Reyes said.

“Maybe Biden hasn’t done too much in the eyes of people for the immigrant community,” he said, adding he thinks people don’t have all the correct information.

“Biden did end up deporting more people than Trump,” Reyes said. “I’d definitely say he’s cracked down on the border as much as he’s able to.”

Enforcement — without the overreach

Odio said Trump may be overreaching by promising mass deportations of the 11 million undocumented adults and children in the U.S.

Odio said Latino voters generally reject the idea of mass deportations of people who have been here for many years, and that leaves an opening for Biden: He can show that he’s committed to imposing order at the border, while also taking a “corrective step” on behalf of people here for decades without legal status.

“That is a very big difference and very powerful among Latino voters, even the swingiest Latino voters,” Odio said.

Advocates say there also is time for the Biden campaign to win back wavering voters by aggressively reminding them of Trump’s explicit promises to execute “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com