Donald Bogle’s “Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks” is considered the standard text on Black characters in American movies. But when the book was first published, in 1973, it was just about the only text on the subject. This might be hard to imagine today, when books about the intersection of race and cinema flow forth on a regular basis (among the strongest in recent years are Will Haygood’s “Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World” and Robin R. Means Coleman’s “The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema From Fodder to Oscar”). Such abundance was unthinkable when Bogle, then a young journalist who had worked as a story editor for Otto Preminger, began his odyssey into the industry’s appallingly racist history. Bogle’s book was practically the birth of the field.

The Ultimate Hollywood Bookshelf

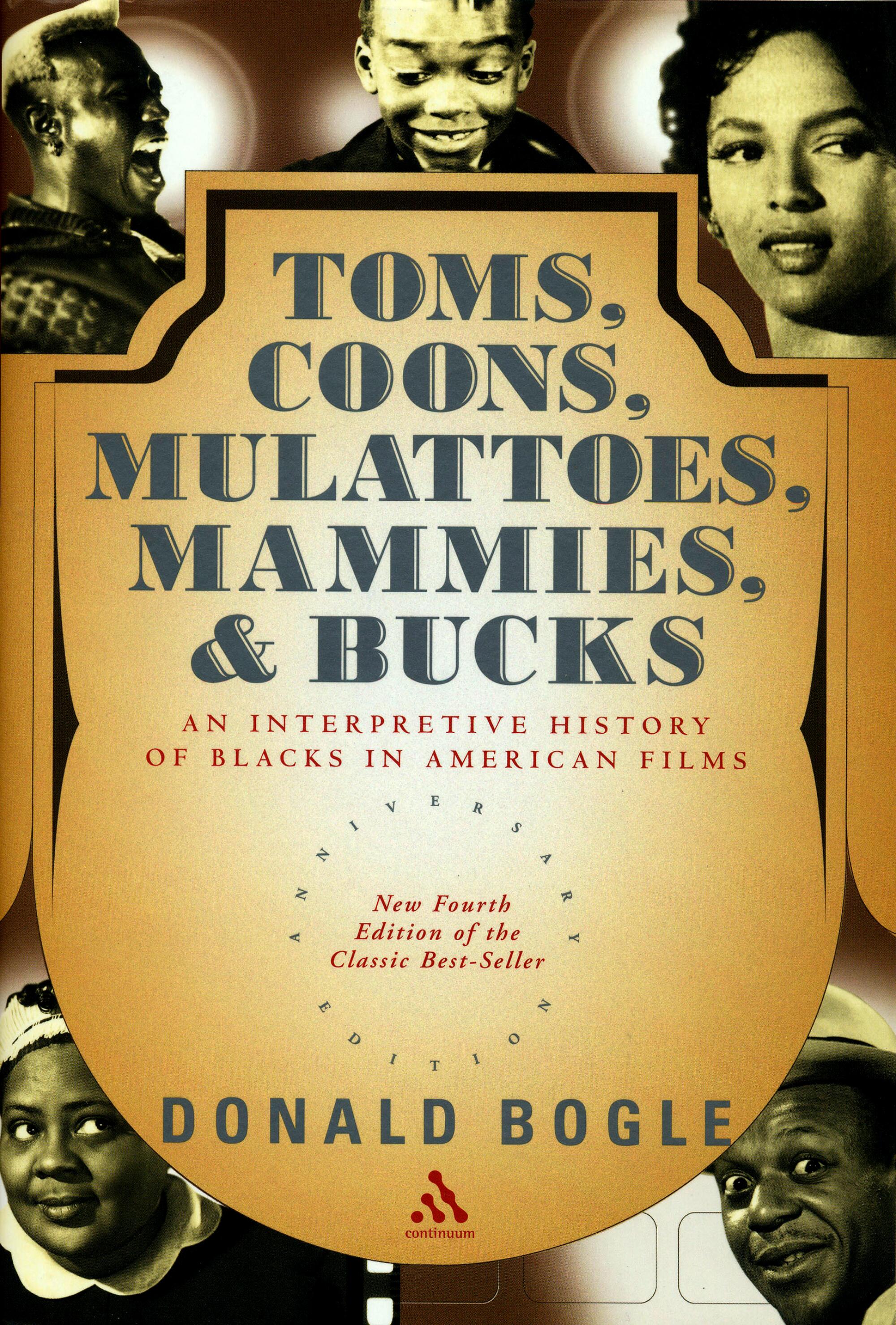

“Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films” ranks No. 39 on our list of the best Hollywood books of all time.

“Toms, Coons” is generally (and accurately) viewed as an accounting of the malicious stereotypes that the movies codified as only the movies can: the obsequious, servile slave; the bug-eyed fool; the tragic, mixed-race sufferer; the happily complacent maid; the violent Black brute. But if Bogle’s book was a taxonomy, it was also a reclamation.

Bogle felt it wasn’t enough to trace and decry the harmful impact of such stereotypes, to show how they fit the pattern of white supremacy on which the country was founded. He also sought to rescue the humanity of those performers who usually had no other option but to play their assigned roles. As he writes in his introduction to the fifth edition, “It seemed to me that a number of talented people were dismissed or ignored or even vilified because no one knew anything about the nature of their work and the conditions under which they performed. No, I thought. The past had to be contended with. It had to be defined, recorded, reasoned with, and interpreted. And I felt it was my task to do so.” What began as a desire to write about Butterfly McQueen for Ebony, where his editors dismissed the “Gone With the Wind” as retrograde and demeaning, turned into a groundbreaking work of cinema studies.

That task could be painful, but Bogle, now 79, had the empathy, even keel and inquisitiveness to pull it off. For instance, in analyzing “Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s 1915 epic that presented a parade of every racist Black stereotype imaginable, Bogle points out that the film was also “a stupendous undertaking unlike anything that had preceded it.” Indeed, Griffith’s pioneering breakthroughs in editing, cinematography and other facets of filmmaking made the stereotypes even more pernicious. Hackwork, after all, is easy to dismiss. The reshaping of a popular art form is not. Bogle understood that the fact of the movie’s abominable racism was inextricable from its role in advancing a medium that would remain abominably racist for many more decades.

As the significance of Bogle’s book became clear, he returned to it over the years, updating and tweaking and revising for new generations of moviegoers and film students and advances in Black cinema. Later editions have taken account of Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy, Whitney Houston and Jennifer Hudson, Denzel Washington and Will Smith, Spike Lee and Ava DuVernay. Readers of the most recent, published in 2016, can jump from Oscar Micheaux’s “Harlem After Midnight” to Ossie Davis’ “Cotton Comes to Harlem” to Murphy’s “Harlem Nights,” from “Birth of a Nation” to “Amistad” to “Django Unchained” to “12 Years a Slave.”

These later editions are arguably not as focused or purposeful as the original, which had a specific mission and set about achieving it. Then again, the parameters of Black film have expanded immeasurably, not just since the early days of the medium but also since Bogle first wrote the book. He remains an indispensable guide to these changes, as much of a pioneer as the generations of artists he brings to life on the page.

Vognar is a freelance culture writer and former Nieman Arts and Culture fellow at Harvard University.