In Kabul, Afghanistan, a major midwifery program — girls’ only higher education option — has closed.

Across Pakistan, dozens of development programs have ground to a halt.

In Bangladesh, a health research center has laid off more than 1,000 employees.

The fallout comes two weeks after U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration suspended foreign aid amid a widespread review, leaving thousands of development programs in limbo.

“I’m in shock,” said a student at the USAID-funded midwifery school in Kabul, speaking anonymously. “This was the last remaining option for girls to receive an education and get a job.”

“People keep calling and asking, ‘When is the program going to restart?'” said the head of a USAID-backed education nonprofit in Afghanistan, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The freeze follows a Jan. 20 executive order issued by Trump that suspended all foreign aid pending a 30-day review.

The president said the review was necessary because “the United States foreign aid industry and bureaucracy are not aligned with American interests, and in many cases, antithetical to American values.” The executive order said the current setup “serves to destabilize world peace by promoting ideas in foreign countries” that undermine “harmonious” international relations.

Now, U.S. government agencies involved in delivering foreign assistance must decide by April 30 to keep, change or end their foreign aid programs.

The aid suspension marks a sharp break with decades of U.S. foreign policy. Historically, the U.S. has been the world’s biggest foreign aid donor, with $68 billion in aid in 2023.

The offices of USAID, the lead foreign aid agency, remain closed. Although the State Department has issued a broad exemption to “lifesaving” humanitarian programs such as emergency food distribution in Afghanistan, most programs on the ground remain closed.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who has taken over as acting head of USAID, said that while he backs foreign assistance, “every dollar” spent on foreign assistance must advance U.S. national interest.

“We are not walking away from foreign aid,” Rubio told Scott Jennings on Sirius XM Patriot 125 on Monday. “We are walking away from foreign aid that’s dumb, that’s stupid, that wastes American taxpayer money.”

USAID is recognized globally as a premiere development agency, but critics at home and abroad have long accused it of throwing American taxpayer money into wasteful projects.

To highlight this, the White House last week issued a list of USAID programs involving “waste and abuse,” including $1.5 million “to advance diversity, equity and inclusion” in Serbia; $47,000 for a “transgender opera” in Colombia; and $6 million to fund tourism in Egypt.

Foreign aid defenders acknowledge the waste, but they argue these projects represent a fraction of the $68 billion U.S. aid program.

South Asia

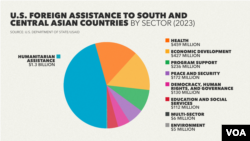

Though U.S. aid to South and Central Asian nations has declined recently, the region still gets billions annually, with Afghanistan the largest regional recipient.

The country, which received $1.3 billion in 2023, now faces a wave of program shutdowns. While emergency humanitarian aid continues after a brief interruption, development programs from child and maternal health to education have stopped.

The impact has been wide-ranging. The United Nations Population Fund has frozen all U.S.-backed programs in Afghanistan, potentially leaving more than 9 million people cut off from health services, according to regional director, Pio Smith.

The UNFPA, which Republicans have long accused of promoting coercive family planning practices, relies on U.S. assistance for almost a third of its humanitarian operations. The agency, which denies the charge, is likely to lose all that support, impacting its work across the region.

Education is another casualty of the aid suspension in Afghanistan. The American University of Afghanistan, established in 2006 with a USAID grant and now operating out of Qatar, has reportedly suspended classes. A university spokesperson could not be reached for comment.

Meanwhile in Bangladesh, the Asian University for Women is scrambling to keep hundreds of Afghan students after U.S. funding dried up. To cover the funding shortfall, the university has launched a $7 million appeal.

“We cannot and will not send these students back to an uncertain and oppressive future,” the university said in a statement.

Bangladesh, despite its $437 billion economy, is also feeling the pinch. The country is a U.S. ally and South Asia’s largest recipient of U.S. aid after Afghanistan, with more than $500 million supporting a wide range of programs from emergency food assistance to fighting tuberculosis and pandemic influenza.

In Pakistan, more than three dozen USAID-funded projects have reportedly shut down in recent days. A burns and plastic surgery center in the northwestern city of Peshawar, built with a $15 million USAID grant, faces an uncertain future.

“At the moment, I don’t know what’s going to happen to the whole program, but I’m hopeful that the program will move forward,” Dr. Tahmeedullah, the center’s director, said in an interview.

Central Asia

In Central Asia, where five former Soviet Republics received about $235 million in 2023, nearly every USAID-funded program and initiative has been stopped, according to local news reports.

“From what I’ve gathered, all types of programs and initiatives have been suspended as of now,” said Alisher Khamidov, a Kyrgyzstan-based consultant who follows USAID-projects in the region.

The suspensions include critical health initiatives such as USAID’s $18 million-$20 million “TB-Free” programs in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, both launched in 2023.

“This five-year project has special significance for Uzbekistan as it was one of the few projects tackling TB in the country,” Khamidov said in an interview last week with VOA.

The State Department did not respond to a VOA question about the current status of U.S.-funded aid operations in South and Central Asia.

USAID has poured billions of dollars into many regional development programs since the early 1990s, including initiatives to promote democratization and civil society. Those efforts, however, represent a fraction of the total aid. Today, the agency is largely focused on agriculture and health projects, according to Khamidov.

Across the region, USAID programs have long faced allegations of waste and abuse, with numerous examples uncovered by the agency’s own inspector general.

Nowhere has the alleged abuse been starker than in Afghanistan, where the Taliban have been accused of siphoning of millions of dollars in U.S. aid funneled through U.N. agencies.

Some Taliban opponents have welcomed the aid freeze, arguing that it could force the group to accede to international demands. Others, such as former Afghan Vice President Amrullah Saleh, say it could level the political playing field in the country.

“The dismantling of USAID clears the path for the rise of genuine leaders in Afghanistan,” Saleh wrote on X.

Bryan Clark, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, says a multibillion-dollar program can inevitably lead to waste and abuse. He told VOA that foreign aid can showcase U.S. goodwill but also cause diplomatic friction over policy and cultural issues.

Clark said that though the aid pause should have been less abrupt, a thorough review of the program is necessary.

“It makes sense to stop as a new administration comes in and reassess where the money is going, where it’s being allocated,” he said.

VOA’s Afghan, Deewa and Urdu Services and correspondent Vero Balderas contributed to this report.