Over and over again, they stretch out their spindly little matchstick fingers into the mighty Pacific, and over and over again, they get their knuckles rapped.

Rapped, broken, burned, smashed to bits.

And yet what do they do? They keep sending those fragile digits out into the ocean, like a middle finger defying the elements.

And that, in sum, is the history, the nature and the character of the piers we have built and rebuilt, have loved and lost, along the California coast for more than a century and a half. If piers were people, you’d have to wonder what insurance actuarial tables would divine about their longevity prospects.

As summer sends more of us out to these cavorting grounds to stand above the ocean and eat and play and fish and don’t-you-dare-smoke, it’s a good moment to know a bit more about them.

For one thing, not all of them are in the trim or even open for business. A fire at the end of April ate through Oceanside’s pier, whose first incarnation was built in 1888. The pier burned for several days, and it may take several years and about $17 million to bring it back from its latest near-death experience.

So what else is new? The seven plagues of California’s piers are fire, ocean storms, fire, old age, civic budgets, ship worms called teredos, and fire.

And still the piers have soldiered on — built, destroyed, rebuilt — some over more than a hundred years, and evolved through the three stages of pier life.

Much has changed at the Manhattan Beach Pier since this postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection was issued, showing a bathhouse and cafe.

What the wharf?

In the beginning, there was the wharf, the rudimentary, workaday pier built to get goods from here to there.

The second, the standard pier, also found an early fan base for fishing and for municipal purposes, and at times it’s been commandeered for military duty.

And the version we love and know best is the frolicsome, often gaudy pleasure pier, redolent of the scents of corn dogs and popcorn and fishy waters. The most renowned of these hereabouts is the Santa Monica Pier, known even to the landlocked from movies and TV.

Probably L.A.’s earliest wharf, Santa Monica’s Shoo-Fly Landing, was built in 1871 so that Henry Hancock could send ox-drawn wagons of asphaltum, “brea,” from his tar-rich inland rancho out to the coast, to load aboard northbound ships to pave San Francisco’s streets. The architectural historian Reyner Banham believed that the wharf planted the seed that grew into Santa Monica, and that the tarry stench that earned the landing its nickname came from the “pee-yew” gesture that folks made, fanning at their noses as they hurried by.

Bigger and sturdier wharves replaced it. In 1875, a railroad built a 1,700-foot wharf nearby to send silver from Inyo County mines to the San Francisco Mint, and to welcome and disembark passengers from the Bay Area.

In 1893, in the battle over which millionaire faction would win the federal tussle for the site of the L.A. port, Southern Pacific built a 4,720-foot “long wharf” snaking out into Santa Monica Bay, and it ran trains full of cargo far out over the water. San Pedro won the harbor battle, and the “long wharf” was left to the gods of storms.

The Stearns Wharf in Santa Barbara, built the first time nearly 150 years ago for commerce, is now a public pier.

And the venerable Ventura Wharf too is now a pier. It was built about the same time as the Shoo-Fly, and it dispatched the area’s cornucopia of produce before it began moving an even richer payload — oil from the fields around Newhall and Santa Paula.

In December 1914, monster seas shoved a steamship carrying a cargo of Christmas toys into the pier, slicing both pier and oil pipeline in half. Uncounted barrels fouled the waters for uncounted weeks. The storms of 2023 wrought havoc on the pier again; the fishermen and day trippers who love it hope that the pledge of a summer reopening will be fulfilled.

1

2

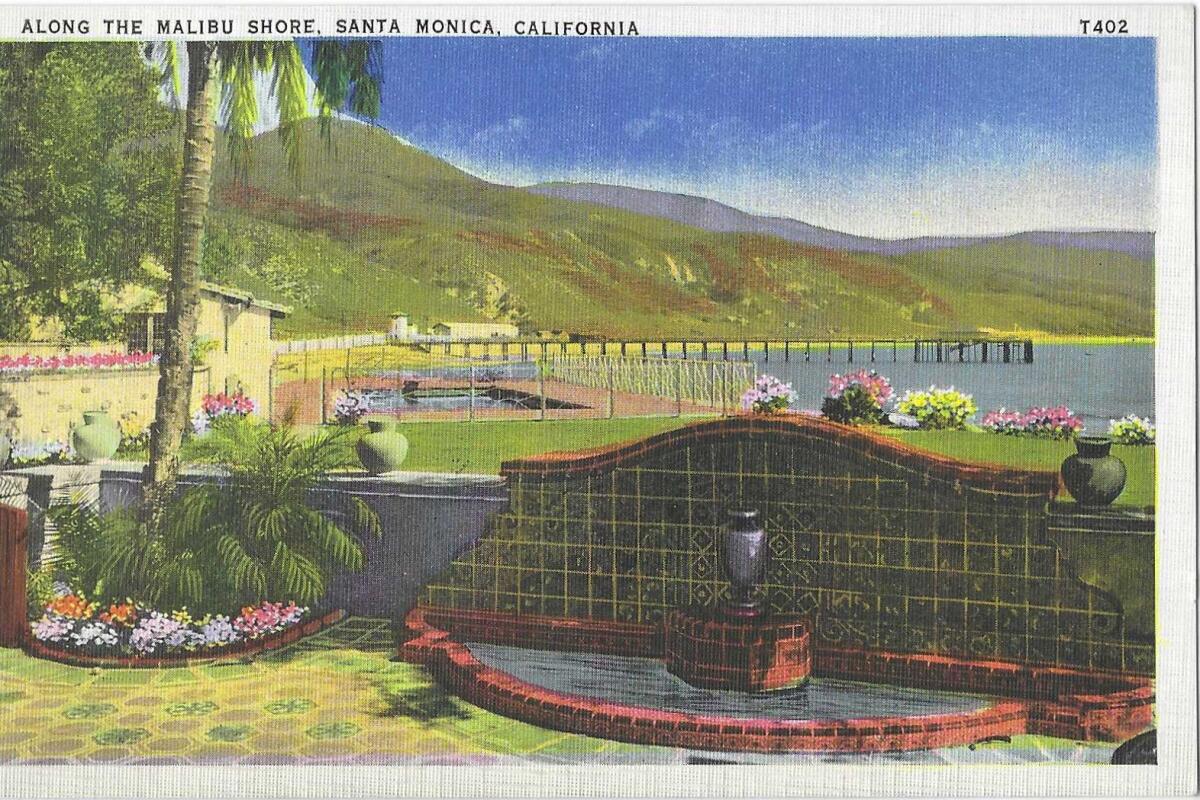

1. A vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection depicts the Malibu shoreline. 2. Another postcard from the collection advertises the Point in Malibu — “cocktails with a shipboard atmosphere.” Today, this is the location of Mastro’s Ocean Club.

Malibu Pier has its origin story in a private wharf built by a legendarily eccentric couple, Frederick and May Rindge. He was a Massachusetts merchant prince, she a Michigan schoolteacher, and in 1892 they bought what would become their 17,700-acre Malibu kingdom. They owned 25 miles — you read that right, 25 miles — of the choicest Pacific coastline.

They policed their land against squatters, surveyors and casual wanderers, and built their own wharf as the rest of L.A. watched and wondered. “March of Railroad Mystery … Plans of Rindge Estate Are All In the Dark,” The Times headlined. Their brilliant stroke was building a small railway to serve the estate’s needs — and to keep Southern Pacific at bay, thanks to a federal law banning the building of parallel competing rail lines. (You can read about the Rindges’ triumph and toppling in the fine book “The King and Queen of Malibu,” by David Randall.)

Like the Rindge land itself, the pier changed, and changed hands. A wartime storm of 1942-43 nearly knocked it to pieces, but the Coast Guard needed it, and rebuilt it. Eventually the modern Malibu Pier — banged up by storms, closed for years, rehabbed and put back on its pilings — wound up in the hands of the state of California, for no local government or private enterprise could afford to keep it going, a fact that a lot of historic piers had to face.

The pier age

Next comes the pier, big brother to the wharf. It was often a public, civic endeavor.

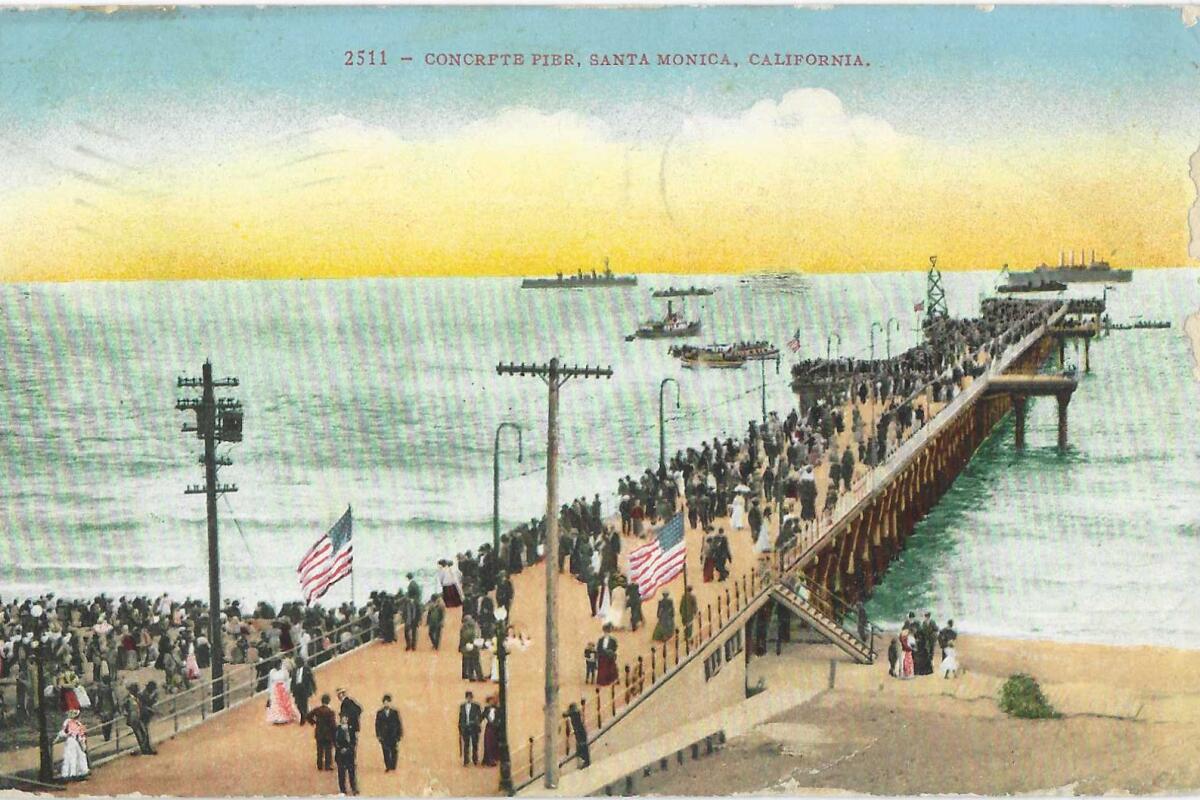

Santa Monica undertook its own pier in about 1908, 1,710 feet long, built not of wood but of modern concrete. Critically, a sewer pipe was slung under the pier to dump the city’s sewage farther offshore, a practice that ended in the late 1920s.

The novelty of a concrete pier was celebrated in a September 1909 gala opening, with a playlet starring Queen Santa Monica and Rex Neptune.

As The Times described it, “A terrible sea monster is seen approaching the pier, red fire blazing from his mouth and eyes … the queen and her court advance to meet him and demand how he dares to show himself in the vicinity after destroying the great number of piers that he has during the last number of years.

“Neptune replies that the destruction of the flimsy structures is considered just so much fun for him, and that he proposes to try his luck on the new pier. … The queen reminds him the concrete age has arrived, and with it the gradual disappearance of wooden piers for him to destroy.”

The queen orders Neptune never to set foot in Santa Monica again, and he climbs a 65-foot tower, and “makes a spectacular fire dive into the ocean and is seen no more.”

1

2

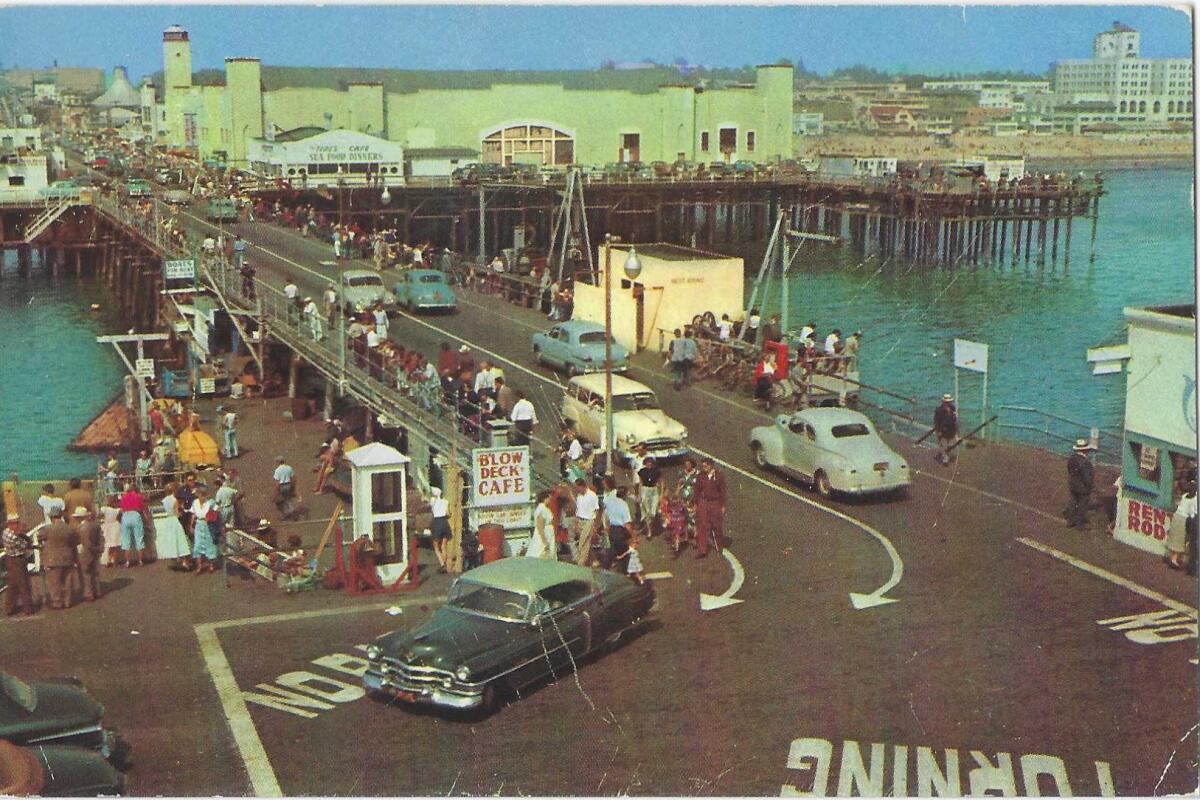

1. “The weather is delightful,” someone wrote on a 1911 postcard from Patt Morrsion’s collection, mailed to Philadelphia that August. 2. A 1958-postmarked postcard from the collection shows a “holiday crowd” on the Santa Monica Municipal Pier.

Well, you know what hubris does. Ten years later, part of the end of the pier collapsed a few feet — with the mayor standing right there on it — and the eternal concrete had to be replaced with the old standby, wood — wood unfortunately treated with creosote, a likely carcinogenic preservative that was for many decades the go-to treatment for pier pilings the entire length of the coast.

In World War II, the military drafted West Coast piers into service. The timbers in the Santa Monica Pier were bolstered to handle the catches from the fishing boats feeding soldiers and civilians alike with its patriotic hauls; one popular World War II poster exhorted, “FISH IS A FIGHTING FOOD — WE NEED MORE.”

In Santa Barbara, the 19th century Stearns Wharf spent part of the war in the hands of the Navy and the Coast Guard. A Santa Barbara history website recounts that the pier’s fishing fleet movements were curtailed “due to concerns over sabotage and fifth columnists.”

This was not defense theater: In February 1942, just up the coast, a Japanese submarine hovering just offshore shelled a Goleta oilfield. It was evening, and workers had gone home, but some oil facilities were destroyed. It was said to be the first attack on the mainland since the War of 1812.

Little wonder, then, that far down the coast, the Huntington Beach Pier was armed as a submarine lookout.

Piers in peacetime

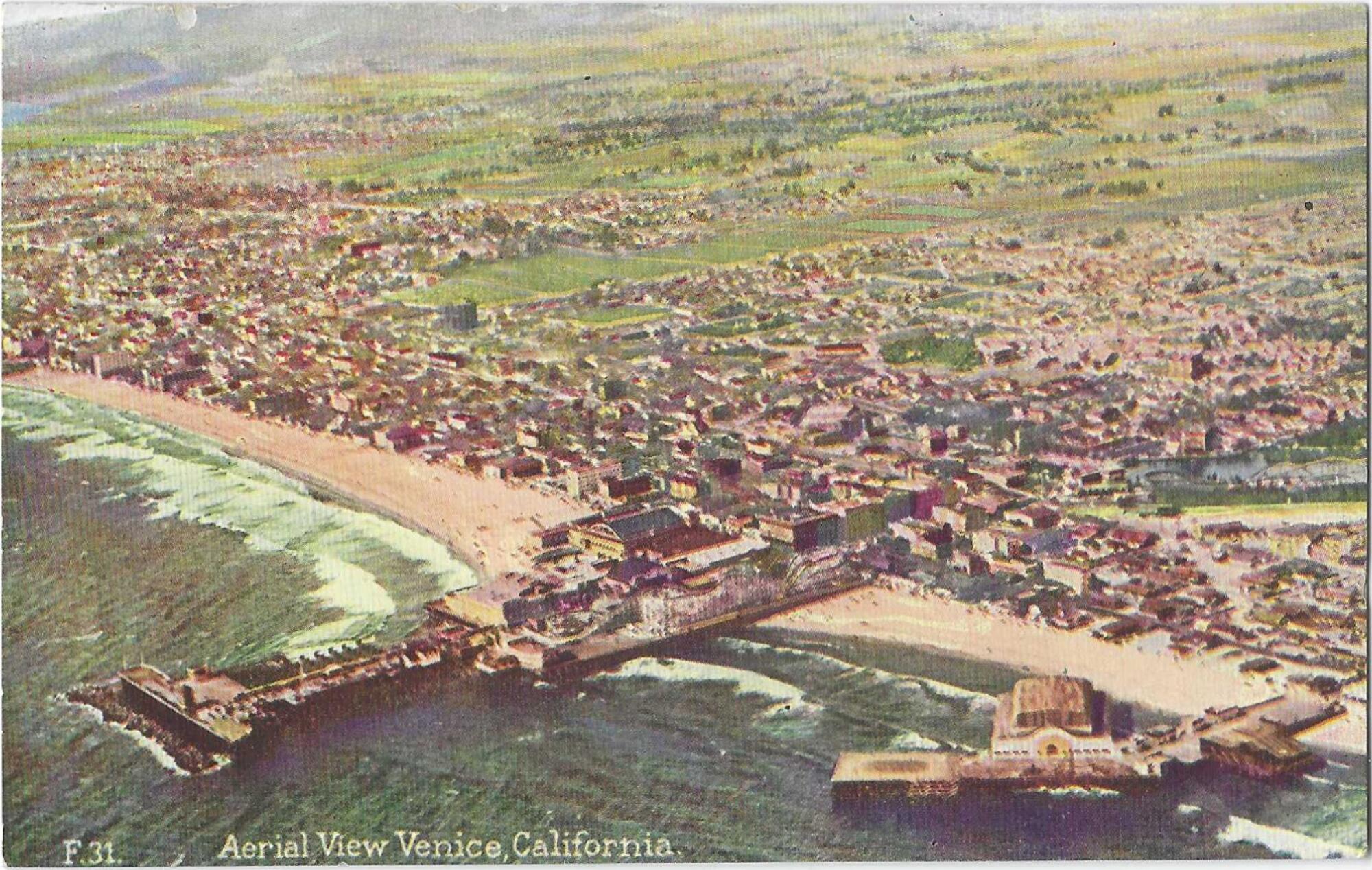

Green open space in Los Angeles? It would appear so on this undated vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection, depicting Venice Beach and its pier.

Ah, but after the war, we get to the full flowering of the pleasure pier.

Before the first World War and until the Depression, pleasure piers had been built, burned and rebuilt along the shoreline sands of Santa Monica and Venice: the Crystal Pier, the Abbot Kinney Pier, the Million Dollar Pier, the Pickering Pier, Frasier’s Pier, the Ocean Park Pier. Their novelties ran to roller coasters, fun houses, live music and theaters; freak shows, animal acts and spooky rides.

In 1912, Frasier’s Pier and several blocks of homes in Ocean Park burned spectacularly, barely a year after the park opened. It was rebuilt a year later and burned down again in 1924.

In 1916, a man named Arthur Looff built a pleasure pier parallel to and wider than Santa Monica’s skinny municipal pier. In one set of hands or another, through one identity or another, it has soldiered on, sometimes barely, through battering storms, the Depression, war, and into celebrity.

Fire is to piers what water was to the Wicked Witch of the West — a ruination. Stray cigarettes, messy wiring, kitchen fires — any little thing can get big, fast.

The Oceanside Pier was on its sixth life, last rebuilt in 1987, when it caught fire in April. The Seal Beach Pier recorded fires in 1992, 1994, 2000 and 2016. But when the city banned pier smoking in 2000 — only a few months after a cigarette dropped on the wooden planks started that fire — some nicotined visitors ranted and griped ad nauseam about their “rights.”

1

2

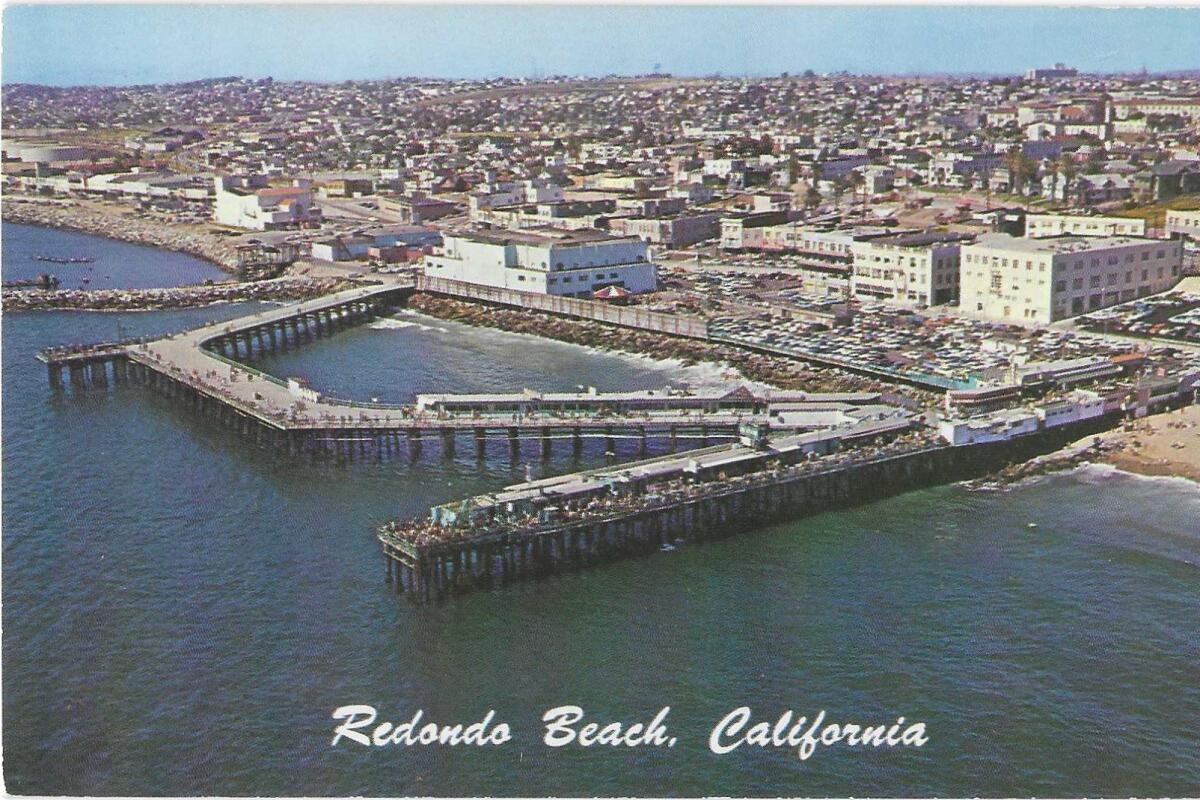

1. A 1960 postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection shows the growth of Redondo Beach’s pier complex — and of the South Bay. 2. The Redondo Beach Pier as it appeared on a postcard from the collection dated July 1922, mailed to a recipient in Iowa.

The Redondo Beach Pier, first built in 1888 as a lumber wharf, burned spectacularly in 1988, perhaps from an electrical short from damage by two immense storms that had just beaten the bejesus out of the place. The pier, once “one of the wildest, bawdiest waterfronts on the West Coast,” was again restored to life.

After the war, the pleasure pier perks up into life once again. Americans had fins on their cars, gas in the tanks, and money in their pockets, and were raring to hit those new interstates.

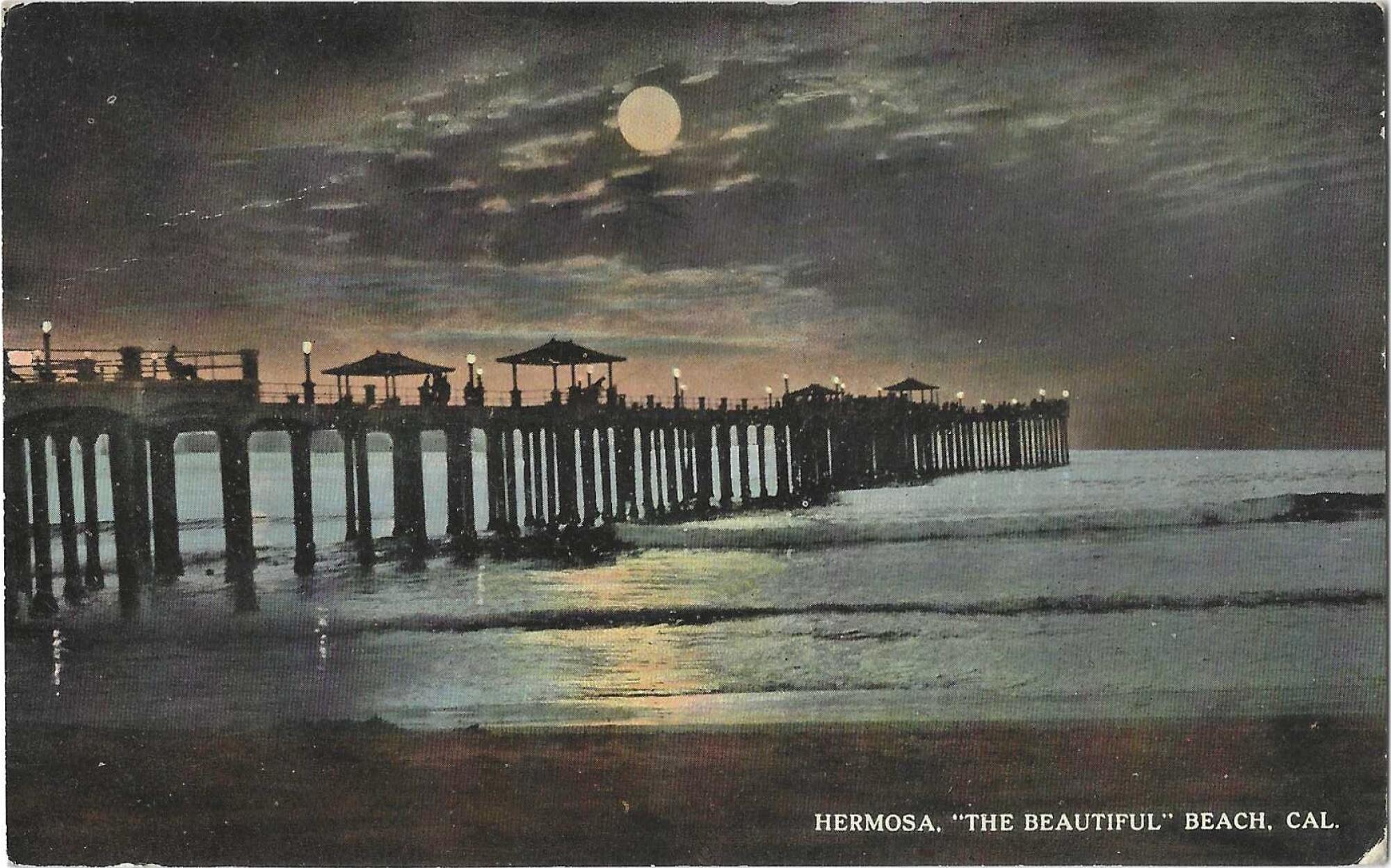

Disneyland’s 1950s opening, in inland Anaheim, was early in a wave of challenges to pleasure piers’ popularity. But a pier has some claim on a civic identity and its affections. If piers were houses, most would have been condemned decades ago, or left to fall to pieces on their own. But again and again, all along the western shore — from Newport Beach’s twin piers, the modest piers of Hermosa and Manhattan Beach (where men couldn’t go bare-chested until 1934), the still-closed beloved fishing pier in Gaviota — people can’t quit their piers.

And it behooves city fathers and mothers to take this sentiment seriously, if they wish to keep mothering and fathering. In the 1970s, the Santa Monica Pier had become practically derelict, an unsavory hangout barely hanging on. The City Council voted to tear it down. In 1973, aggrieved Santa Monicans jammed into the council chambers and made their feelings known. The council majority held fast: thumbs-down on the pier. Citizens passed a hands-off-the-pier initiative, and in the elections of 1973, every council member who voted to tear down the pier found himself voted out of his job.

Nighttime at the Hermosa Beach Pier, depicted on this 1915-postmarked postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.