John Wilkes Booth assassinated Abraham Lincoln. Most Americans know that much history. But the true story goes deeper than one man firing one bullet.

When Monica Beletsky learned the assassination was part of a conspiracy, and that similar attempts were planned for Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward that night, she was shocked.

“I grew up thinking that stuff happens in other countries,” says Beletsky, who has previously written for “Friday Night Lights,” “Parenthood” and “Fargo.” “I wondered why this part of the story has been in the shadows and thought about how it shows how strong our democracy is and also how fragile it can be.”

Reading further, she learned about Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s close friend and ally and the forgotten hero who led the chase for Booth and oversaw the subsequent conspiracy trial while fighting to keep Reconstruction alive and battling dangerous health issues. This, she thought, was a man to build a story around.

When she pitched Apple TV+, executives there told her the rights to “Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer,” James L. Swanson’s 2006 bestselling book, were available. “It was just a treasure trove of research,” she recalls.

“Manhunt,” starring Tobias Menzies (“The Crown”) as Stanton and Anthony Boyle (“Masters of the Air”) as Booth, with Hamish Linklater as Lincoln and Lili Taylor as Mary Todd Lincoln, puts Lincoln’s death back into that fuller context. The first two episodes are now streaming.

“History is always super complex and messy, and people usually prefer the two-sentence story,” says Patton Oswalt, who plays Lafayette Baker, a semi-shady investigator who aids Stanton in the hunt for Booth. “There’s so much more to this story: the enormity of the plot against the Union and the chaos and terror after Lincoln was shot — the pursuit of Booth was a race against time, since he was trying to reignite the Civil War. He might have done it if he’d made it to the South.”

“History is always super complex and messy, and people usually prefer the two-sentence story,” says Patton Oswalt, who plays Det. Lafayette Baker in “Manhunt.”

(Chris Reel / Apple TV+)

Swanson wrote his book as a thriller and always envisioned it on the screen, selling the rights well before publication. Early announcements were for a film starring Harrison Ford as Stanton, but ultimately, the author is glad the movie version never happened. “It’s better suited as a series because there’s too much to capture in a film; you wouldn’t be able to flesh out all the characters,” says Swanson.

In preparation for his role, Menzies watched Ken Burns’ “The Civil War” to understand how that period was “drenched in conflict” and read Doris Kearns Goodwin’s “Team of Rivals” to understand the era’s politics. “That was a real touchstone for me,” he says, adding that they did take artistic license with Stanton’s approach to facial hair, which in reality was “very whiskery.”

Actors with smaller roles also dove in deep. Matt Walsh, best known for a very different political series in “Veep,” plays Dr. Samuel Mudd, who fixed Booth’s broken leg after the shooting. (It’s largely forgotten that Mudd, who had been violent toward his slaves, knew Booth and had met with other conspirators.) Walsh read Mudd’s letters, where the doctor explained why he was canceling a magazine subscription — it declared slavery was not something that Jesus would have approved of.

“I realized he had a religious security that he wrapped around his superiority,” Walsh says. “I played him as someone who in his own mind was a good man, healing people, rich and poor.”

While the hunt for Booth and his conspirators propels the story forward, flashbacks underscore the relationship between Stanton and Lincoln, which Menzies calls the story’s “emotional heart.”

“Stanton pushed Lincoln on the slavery issue and others, but Lincoln’s great genius was his ability to take people that didn’t want to come on that journey with him,” Menzies says. “Stanton was someone you’d want in a crisis, and he was often on the right side of the argument, but he didn’t have that capability.”

Linklater agrees, saying Lincoln had the unusual ability to “hold doubt and uncertainty in his mind and not have it create anxiety,” while “Stanton was the moral spine of the administration.” In the series, he added, “You get to see them pushing and strengthening each other.”

Hamish Linklater, who plays Abraham Lincoln in “Manhunt,” says the president had an unusual ability to “hold doubt and uncertainty in his mind and not have it create anxiety.”

(Chris Reel / Apple TV+)

The two actors say those conversations give a sense of what has been lost with the assassination, underscoring Stanton’s motivation to catch Booth and fight Johnson on Reconstruction, even as his own health was failing.

“Stanton is one of those American figures who quietly showed up and did the job and did not get the credit that they deserve,” Oswalt says.

Swanson believes Menzies nailed Stanton’s “imperiousness, heroism, dedication and relentlessness.” And while Linklater felt daunted by playing a man he admires, and one who was memorably portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” (“He was like an angel portraying a saint in the most beautiful performance ever”), Swanson believes Linklater fully embodied the president.

Boyle plays Booth as both vainglorious and self-pitying. When I mentioned to Beletsky that in crucial scenes he seemed to be channeling the Al Pacino of “Dog Day Afternoon,” she noted that they had discussed Pacino before filming those moments.

Swanson says it was important that Beletsky and Boyle not depict Booth as an antihero or a romantic, misguided youth. “He was a racist and a murderer who killed the greatest president and one of the greatest Americans, period.”

With Stanton hunting Booth and tracking an entire conspiracy from Georgia to Montreal, a huge cast was required for all the soldiers and government employees. Linklater gets choked up recalling the scene in Episode 1 with the extras in the War Department’s telegraph room when they got the news that Robert E. Lee, the leader of the South, has surrendered. “I was in a room of citizen actors and they all carried that tremendous moment,” he says. “It was a wild scene.”

1

2

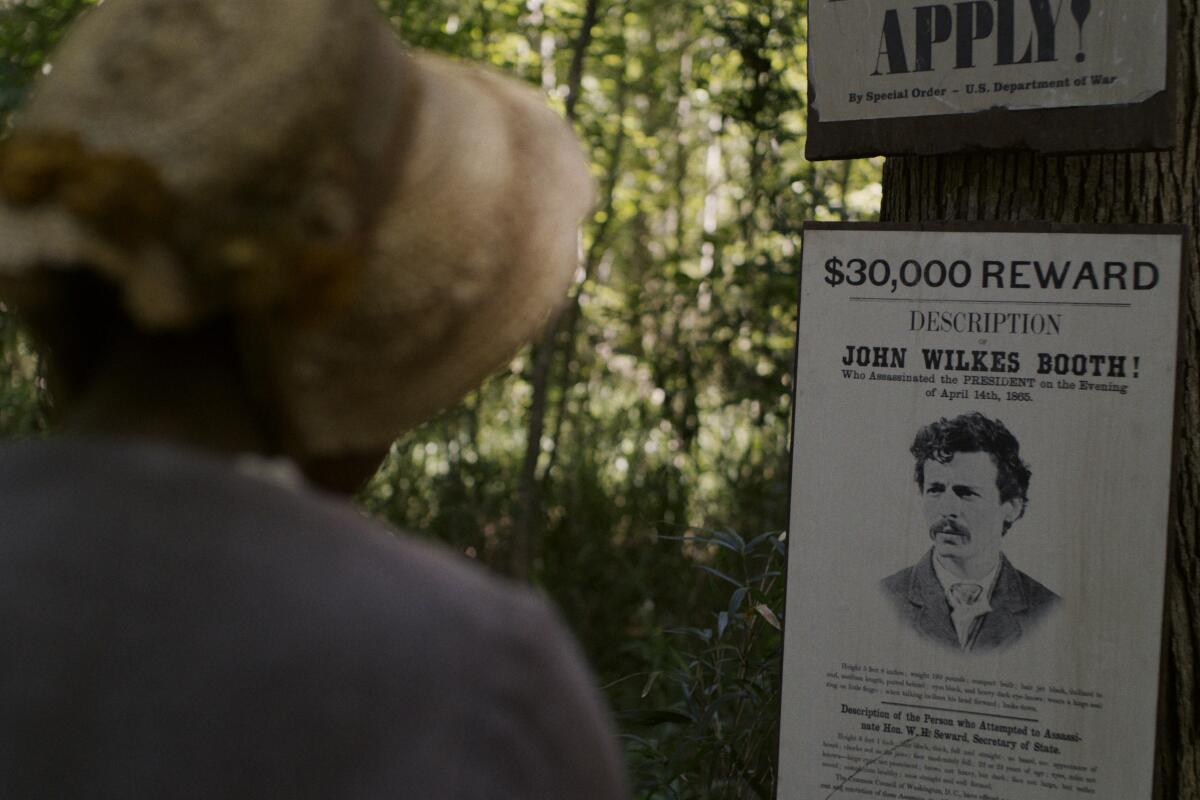

1. A reward poster for John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, in “Manhunt.” (Apple TV+) 2. John Wilkes Booth (Anthony Boyle), left, with David Herold (Will Harrison), who was an accomplice. (Chris Reel / Apple TV+)

The story’s sprawl created “an enormous undertaking,” Beletsky says, with more than 200 sets required. One challenge was replacing Ford’s Theatre, which wasn’t available. “We needed one that was convincingly period but also had a balcony close enough to the stage for Booth to jump down after shooting Lincoln,” she says. The scene was shot at Philadelphia’s Miller Theater. (“That’s my hometown, so I got to put my mom in a gown and put her in the audience,” Beletsky says.)

Beletsky also used the seven episodes to give life to Black characters who often were left out of the telling of pivotal moments in American history. Swanson found Beletsky’s approach fitting, because when Lincoln lay dying, the vigil outside his window was largely Black Americans, for whom the future was suddenly shifting. “If this had been a movie, there would likely not have been enough time to show this side of the story,” Swanson says.

For the record:

1:44 p.m. March 15, 2024Former slave Mary Simms is shown reading in the series but it is unclear if that is historically accurate. Also, in the series her testimony in the conspiracy trial was combined with that of two young women.

Beletsky shines the spotlight on two Black characters: the poised and eloquent Elizabeth Keckley (Betty Gabriel), who bought her own freedom, earned 27 patents over her lifetime, wrote a memoir about being Mary Todd Lincoln’s seamstress and confidant, and was an activist for Black Americans after the war; and Mary Simms (Lovie Simone), one of Mudd’s former slaves, who became one of the first Black women to testify in a courtroom during the conspiracy trial.

“I think there’s a version where the show could have just been a cat-and-mouse between Stanton and Booth,” Beletsky says, “but as a mixed-race Black woman, it was important to show what losing Lincoln might mean. And Black history is often thought of as separate from American history, so it was exciting to show that’s not true.”

Lovie Simone plays “Manhunt’s” Mary Simms, who became one of the first Black women to testify in a courtroom during the trial of John Wilkes Booth’s conspirators.

(Chris Reel / Apple TV+)

Simone found Simms appealing because her role brings humanity to a character in a time period “where I haven’t seen humanity for people that look like me.” There wasn’t a lot of detail for her to research, however. “There’s more information out there about Booth’s horse than Mary Simms,” she says. “That’s the country that we’re coming from.”

Simms is one of the characters with whom Beletsky took artistic license: She was gone from Mudd’s home by 1865, and Beletsky combined her nearly verbatim testimony with statements from two black teenagers who still worked for him. The show also tweaks the details of what happened on Booth’s last night to emphasize his delusions of grandeur, but Swanson says as a historian, he has no quibbles.

“I’m not a nitpicker because no filmed entertainment can capture every single fact of a book,” Swanson says. “The way I evaluate any historical drama is whether it conveys the mood of the times and the characterizations of the people accurately. And this series really gets the mood of that time and the sense that nothing was inevitable.”

He also was impressed with the attention to detail on the set, like on the day when Taylor asked how Mary Lincoln would enter a room where Lincoln and Stanton were conferring. He told her, “She was imperious and short-tempered [and] would not knock; she’d march right in and interrupt the president to make her point.”

Beletsky was drawn to this story not just because it’s dramatic but because it still resonates in an America where many people, particularly in the former Confederacy, are aggressively striving to dismantle not only decades of progressive policies but even our democracy itself.

Portraying Booth as an insecure loser driven by personal grievance drives home the connection to both Donald Trump and the Jan. 6 insurrectionists. “I think that Booth is similar to figures you see today,” Beletsky says. “He couldn’t accept the outcome of the war and he took it into his own hands with an act of violence.”

Oswalt says that the series gave him a “sense of comfort” by showing “we’ve been this close to the edge before and pulled ourselves back,” although he quickly added the caution that “every great nation has near misses and saves itself only until it doesn’t.”

With an election coming up, a series about a time when the future of America’s democracy was under threat feels not just relevant but necessary, Menzies says. “One can fall into hyperbole about this, but it’s hard not to feel that this story has something to teach us.”