To Nicole Brown Simpson’s sisters, she was the quiet, serious one — the one who bit her fingernails down to stubs but also loved to entertain and throw lavish parties.

But in the 30 years since she was stabbed to death, along with her friend Ron Goldman, in a horrific crime that became one of the most defining moments of the 1990s, that sense of her humanity — of who Nicole was outside her doomed, abusive marriage to football star O.J. Simpson — has gotten lost amid the sensationalism.

Her sisters Denise, Dominique and Tanya Brown are hoping to correct this imbalance with “The Life & Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson,” a four-part documentary focusing on the woman at the center of one of the most notorious murders in modern history.

Premiering June 1 on Lifetime and airing over two nights at 8 p.m. Pacific, the series includes interviews with roughly 50 subjects involved in the case, including journalists, lawyers and infamous figures like Brian “Kato” Kaelin.

But it also features intimate home movies and photographs, many taken by Nicole herself, and includes moving recollections from family and longtime friends who can speak to the woman they knew. The documentary brings her voice to life in a way that has rarely been seen, and it stands in contrast to the countless books, podcasts and TV shows about the murders.

Viewers learn about how Nicole was born in Germany but became the quintessential California beach girl, the second of four daughters, who enjoyed an idyllic childhood in Orange County. They also hear about the troubling origins of her relationship with O.J., whom she met a few weeks after she turned 18 — and who was reportedly violent to her from their first date. The series revisits the televised trial, which became a media circus and resulted in a shocking not guilty verdict. But it also looks at the painful aftermath for the Brown family, who were forced to relinquish custody of Nicole’s two children, Sydney and Justin, to O.J. and find their own ways of protecting her memory.

By coincidence, the series arrives less than two months after O.J.‘s death at 76, an event that sparked yet another wave of interest in the murders and a flurry of think pieces about the man widely believed to have committed them — rather than the victims.

The Brown sisters recently gathered at the Manhattan offices of A&E Networks to talk about their sister — and why they decided that, after 30 years, it was finally time to tell her story.

The Brown family, from left: Dominique, Nicole, Denise, Juditha and Tanya.

(The Brown family)

There have been many documentaries about this case over the years. Why did you want to participate in this one?

Dominique: To humanize Nicole. I think she was lost in the circus and the havoc in the media. She was portrayed poorly. It was time. A lot of years have passed. It’s completely ironic that it coincided with O.J.’s death. It’s been in the works for —

Denise: … over a year. I was actually working with [executive producer] Melissa Moore probably 10 years ago. I wanted to do something on the 20th anniversary, but that just didn’t feel right. I ended up talking to Melissa again. I said, “It’s either now or never.” I asked Tanya and Dominique, “Do you want to do this now and really let Nicole’s voice be heard?” Lifetime had the same vision that we did. Everything else was always about him [O.J.] and the trial. What I like about this is that, regardless of where they go in the documentary, it always brings it back to Nicole.

Dominique: … as a mother, as a person, as a friend. As somebody who’s starting to find freedom in her voice.

What do you wish you had understood about domestic violence when Nicole was alive?

Denise: I wish we would have known about domestic violence, period. We didn’t know anything.

Tanya: You don’t know what you don’t know.

Denise: That’s why it’s so important to educate the new generation and the young people that have no clue. Especially when they walk around with their bruises showing, and [they’re] proud of them. They’re doing that!

I think [viewers] will get a sense of who Nicole was as a person, and how things progressed and changed. If we can educate a whole load of people, awesome. If we can educate one person, that’s good, too. We can do that and save a life.

Dominique: I find notes on [Nicole’s] headstone with flowers. I have copies on my phone of letters from women that have left notes saying, “If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have walked away.”

Tanya: I still get emails. “If it wasn’t for your sister, I’d be dead.”

What are your memories of the trial and how Nicole was portrayed in the media?

Dominique: It really turned into a circus. It was a bunch of performers.

Denise: Nicole and Ron totally got lost. They just did not exist anymore. It was more about winning. It was more about race. It was more about the ugliness and everything else but them.

Tanya: There were people selling merchandise.

Denise: We saw a lot of this [in the documentary] and it was like, wow. Because we were always taken underground [during the trial] then we were taken up in the courthouse. So [we] bypassed that whole circus out front where they were selling things.

Tanya: I was walking in the harbor with my mom and the Coast Guard was flying in a regular helicopter. And she was like, “Oh my God, what’s that?” I go, “I know, Mom.” I still get that trigger. It brings me back there. We got a lot of helicopters at home.

Dominique: I used to take the kids to the beach and the helicopters would follow us. So we would make a game out of it. Someone would go, “Look, helicopter!” We’d grab our towels and run to the beach. We had to make a game of it. “They’re gone now. You can play again.”

How did you find a way to mourn your sister in the middle of this circus?

Dominique: I think all of us did it differently.

Tanya: It bit me in the butt after 10 years. I attempted suicide. Not just [because of] Nicole, but from unresolved grief and pain from losing a lot of friends when I was younger. I never faced it and then a trigger happened. My wedding was canceled. That’s when I started spiraling — pills, alcohol. I got into the psych unit. I found myself very angry at Nicole because she didn’t tell me [about the abuse]. There was an incident in 1992. We were out for New Year’s Eve. We were at [the restaurant] Spago. She goes, “I’m asking O.J. for a divorce tonight.” I said, “What?” She goes, Don’t tell Dita or Opa,” our parents. I was like, “I’m not holding on to that.” I immediately told my mom. I don’t know what happened after that. It was that incident [at dinner in 1992] that got me. That’s what brought up my anger. I know why she didn’t tell me [about the abuse]. She was terrified, because she was the only one who knew what he was capable of doing. Maybe not only to her, but to us too.

Dominique: It was Jekyll and Hyde. She knew [O.J.’s] good side. That’s what she was holding on to.

Denise: I ran — an hour, hour and a half a day. When I didn’t go to the trial, I was running. That was how I could release my frustration and anger. Then I went out and spoke. I started speaking in March of ’95. That was really cathartic because I learned about domestic violence, I met women and children in shelters. They’re the ones that educated me. I heard frightening stories. Some of [the women] wanted to go back [to their abusers]. There was this little, frail woman in Atlanta; she had burn marks up and down her arm and on the back of her neck. She had singed hair. Her husband forced their son to take cigarettes and burn her on the back of her neck. Her own child had to do that! It was Nicole who started me doing this, but it was stories like that that kept me going.

Tanya, Dominique and Denise Brown say they each had their own way of mourning their sister’s death.

(Oliver Farshi / For The Times)

Dominique: Denise had her own way of grieving. I immersed myself in the children. We played and we played, and that’s all we did. I went to court when I could, but usually I was home with the kids, so my parents could go. Between Nicole[‘s kids], Denise’s [son] and my son, there were the four [kids]. That’s how I got through. Because I felt that that’s what Nicole would have wanted me to do — to take care of them.

Denise: I thought we were going to start the foundation and domestic violence was not going to exist anymore. Thirty years later, we are still in it. The Violence Against Women Act [, which provided resources toward combating domestic violence,] was passed after Nicole’s murder. A year later, the 24-hour domestic violence hotline was created. They’re saying now that they’ve had over 7 million calls that somebody has answered, but that doesn’t count the calls they could not answer because they didn’t have the resources to answer them.

When Nicole’s kids went to live with their father after he was acquitted, it must have felt like losing her all over again.

Denise: All over again. I think it happened a couple of times. It happened when my mom died. It happened when [Nicole’s] dog [Kato] died, because he was so close to our mom. He was her connection to Nicole. That was another thing that just killed her. She just loved him so much. And then when the kids were taken away on Christmas [1996, when O.J. was granted custody after his acquittal]. That was horrible.

Has participating in the documentary been helpful at all?

Denise: For me, I think it was probably harder this time around. Earlier, I was in shock. The first time we did any kind of interview[s], I was more in shock than anything. Reliving it 30 years later, there’s no shock there anymore, just raw emotion. I said, “Gosh, you guys had me crying all the time.” [laughter] I was heartbroken. It just came flooding out.

Dominique: It was a lot. I had to dig pretty deep to remember after 30 years. It was definitely emotional thinking about all those things again. I remember buying books at the airport, and there’d be a reference [to Nicole’s murder] in it.

Tanya: Or sitcoms. It was everywhere. “SNL.” Still today, you’ll watch “SVU” and they’ll reference it. I’m like, here we go again.

Denise: You know what was really good though? In the community that we lived in, there was a [supermarket]. The stores that we would go to would … turn around the tabloids.

Dominique: I remember them taking them totally off [the stands].

Denise: Some stores took them off. Others, we would call beforehand because the kids were coming in with us. They were really great about stuff like that. Everybody cared about the kids. It was all about them. It still is.

Did they watch this?

Tanya: I was thinking about it this morning and I was crying. I hope they don’t [watch]. But I don’t know. Dominique is closest to them. I think it would hurt them because at the end of the day, it is their dad.

Dominique: It’s important to me [to talk to them]. Their kids don’t have a grandma, or a great-grandma. My mom is dead — Dita is what they called her. And they don’t have one grandpa. I’m a great-aunt to the children but they have little names for me, like a grandma. I’m Grandma Mini.

When O.J. died last month, what was your reaction?

Dominique: We were all texting each other, trying to find out if it was real. Tanya had gotten a phone call. She texted me. I said, “God forbid, but I’m putting on news.” And it was verified. I was just sad. I don’t know if it’s an end to a chapter, or the beginning of something new. But I was sad for the kids that their father died. I don’t talk to them about their relationship with their father. It’s very complicated.

Tanya: It was very complicated because of Sydney and Justin. But after watching the documentary last night, I’m like, “Good riddance.” When Caitlyn Jenner said that, I was like, “God, that was kind of harsh.” Now I’m like, “Good riddance.” Hearing [Nicole’s] diary entries and listening to the [police] and the investigators, I was like, “This guy’s a horrible, horrible person.” The world is better with one less bad person in it. You caught me on an angry day, but that’s OK. I need to feel this. I was crying all night last night. Didn’t sleep a wink. I’m crying right now. It’s hurtful listening to how much pain was inflicted on her. I’ll leave it at that.

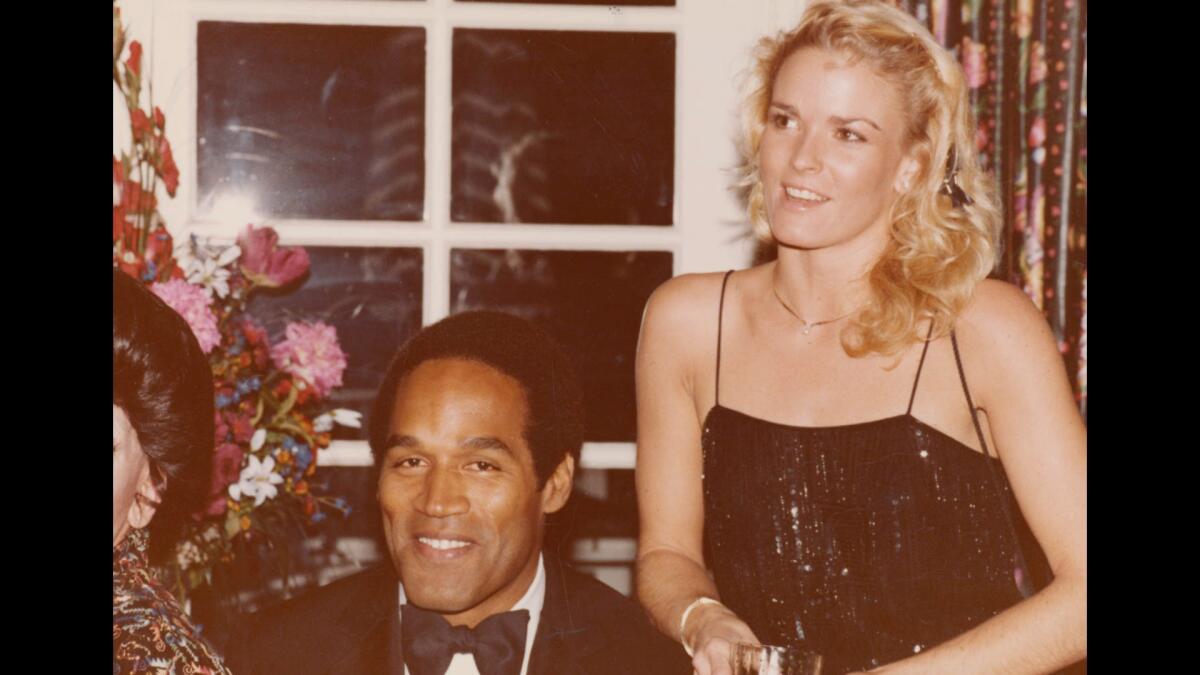

O.J. and Nicole Brown Simpson, pictured together sometime in the early 1980s.

(Brown family)

Let’s talk about Nicole. What are some of your favorite memories of her?

Denise: God, I have memories going back to Germany, picking berries in my grandparents’ garden. Moving over here to the States, not speaking a word of English. I think that’s why we were so close. We would talk in German if we didn’t want people to understand us. We had that kind of relationship. And then, of course, we had boys and horses. We’d always be at the stables together, too. Nicole and I back in the day used to hitchhike down to the beach.

Dominique: That’s why we moved to Laguna Beach. Because of the hitchhiking! Daddy didn’t want them to hitchhike anymore.

Denise: We got caught a couple of times. We would always say, “Oh, no, a friend’s parents are taking us.

What was her role like in the sibling dynamics?

Denise: She was the mature one — pretty serious. Everybody always thought Nicole was older than me. She hated that. I would try to get a six- pack of beer. There was no way that anybody was gonna sell me a six-pack of beer. Nicole would walk in and they’d sell her a six-pack of beer. I’m like, “How did you do that? You’re younger than me!”

Tanya [to Dominique]: I think you two are most alike.

Dominique: Nicole and I were a lot alike. She could do anything, and I can do anything. If I don’t know how to [do something]. I’ll tell you what — I’ll figure it out. She was the same way. She’d be on the roof putting up Christmas lights. Nic and I were pregnant together. I loved that.

One of my favorite memories was the last trip we took to Puerto Vallarta [before she was killed]. She was free and she danced. We hung out by this beautiful pool and we just sunbathed on the beach. That’s how she was when she was younger. She had a freedom, an airiness — just a beauty about her. It was Nicole as she should have been all along.