This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered three times a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

One of the great debates in the energy transition is how to strike the right balance between investing in radical new technologies that are untested at scale, and in rolling out the green technologies we already have.

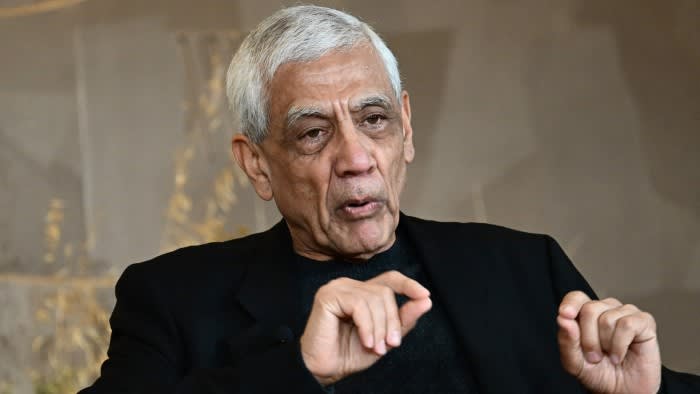

Vinod Khosla, a leading investor in this space for two decades, is firmly in the former camp, as he made clear to me during a recent conversation in London. Khosla is pursuing a stubbornly high-risk approach to climate tech investing, with an acceptance that many of his bets will fail, while those that succeed have a chance of making a massive impact.

And as you can see below, the volatility in investment sentiment towards these sectors, and more broadly in the political and trade arenas, doesn’t seem to be damping Khosla’s risk appetite.

Green tech investment

How a storied clean tech investor is thinking about the future

Vinod Khosla can fairly claim to be one of the pioneers of clean tech investment. Having made a fortune as a founder of the software company Sun Microsystems, Khosla set up his eponymous venture capital firm in 2004, and soon adopted a major focus on the green transition.

There have been some painful setbacks during that time — notably in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, when valuations plunged across much of the green technology space.

But Khosla has retained a big focus on low-carbon technology, while making big bets on other areas such as artificial intelligence — including a well-timed 2019 investment in OpenAI.

While some other investors are getting nervous about the outlook for green tech, amid policy uncertainty and flagging valuations, Khosla sounded bullish during our recent conversation in London.

A key pillar of Khosla’s strategy is to invest in technologies that will prove cost-competitive without relying on long-term support from subsidies, or on future carbon pricing moves that will push up the cost of today’s high-emitting industrial producers.

In steel, for example, Khosla was unenthusiastic about the outlook for start-ups such as Sweden’s H2 Green Steel and Hybrit. As I saw on a visit to northern Sweden, the Hybrit system has started producing low-carbon iron and steel — but at a significant premium to conventional steel, at today’s prices.

“Will it be as cheap as regular steel? The answer, for most of the technologies I’ve seen, is no: it’ll always be more expensive, which means it can’t scale,” Khosla said.

Tougher carbon pricing regimes could eliminate that premium, I noted — but Khosla is not impressed by this argument. Instead, he’s investing in companies pursuing radical approaches with high technical risk — that is, a serious danger that their systems may not work as hoped, but which would prove highly cost-competitive if they do. One of these is California-based Limelight Steel, which wants to replace coal-fired blast furnaces with furnaces using lasers.

Other investors “minimise technical risk, but then they end up with products that are more expensive”, Khosla said. “I’d rather take the larger technical risk upfront.”

One of the biggest technical risks Khosla has taken was his bet on Commonwealth Fusion Systems, the most richly funded of a new wave of start-ups aiming to commercialise fusion power. This energy source could provide vast amounts of carbon-free electricity, but has so far eluded the concerted efforts of many of the world’s top nuclear physicists. CFS is currently building a prototype fusion plant in Massachusetts (featured in our documentary on fusion power), which it expects to have up and running in 2027, its chief executive Bob Mumgaard told me last month.

More recently, Khosla has turned his sights on superhot geothermal energy, which uses new techniques to generate more power from subterranean heat than conventional geothermal plants, by using the higher temperatures found at greater depth. His firm has invested in two start-ups developing technology in this space: Quaise and Mazama Energy, both based in the US. “If you drill deep enough, you could do it in most parts of the world — not just the known geothermal locations,” Khosla said.

In transport, too, Khosla has focused on companies developing disruptive new technologies rather than those making incremental improvements or finding ways to deploy technologies that already exist.

He’s invested in QuantumScape, a California-based company developing a new type of solid-state battery that it says would have much better performance than those currently on the market. QuantumScape’s valuation jumped to nearly $50bn soon after its 2020 flotation only to slump to less than a tenth of that sum — though it enjoyed a 25 per cent jump last week when it announced a new licensing deal with Volkswagen.

More recently, Khosla has joined those looking beyond private passenger cars for the future of urban transit, through an investment in Glydways, a start-up developing autonomous vehicles for public transport. Its vehicles will follow fixed routes, meaning there is far less risk of collision, and therefore they can be far more lightweight than conventional cars while still satisfying safety regulators.

The outlook for regulation around these industries, and green policy more generally, looks especially uncertain this year after a shift to the right in EU elections and another widely expected in November’s US presidential election.

While that has spooked some investors in the green tech space, Khosla stressed his focus on finding businesses strong enough to thrive in the long term without strong support from government policy.

“If the spending on subsidies gets too large, we will see a backlash. So it’s better to use whatever capacity we have for spending on technologies that need support for shorter periods of time to get to economic competitiveness,” he said.

He took a sanguine view, too, of the growing trends of green protectionism, as both the US and EU use tariff barriers to reduce their reliance on Chinese clean tech manufacturing. This, he said, “will set the world on a very different path for industrial development” — creating yet another wave for investors like Khosla to surf.

“I always say a crisis is a terrible thing to waste,” he added.

Smart read

Martin Sandbu warns that a slowdown in EU battery manufacturing investment “exemplifies a broader problem: a private sector deeply lacking in faith that its political leaders can move from words to action”.

Recommended newsletters for you

FT Asset Management — The inside story on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar industry. Sign up here

Energy Source — Essential energy news, analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here