In the summer, when the temperature in Phoenix’s north valley climbs well above 100 degrees, the heat would rise like a vapor cloud from the asphalt parking lot that hugged Ozzie Ice’s two mini rinks.

“You’re trying to keep an ice cube frozen in the oven,” said Sean Whyte, a former Kings winger and hockey director at Ozzie Ice before the rinks were melted for good and the space converted into a rock-climbing gym.

Whyte grew up in Canada, where kids played hockey on frozen ponds. The desert, on the other hand, was more conducive to growing cactus than it was to nurturing NHL scoring champions.

At least that’s what Whyte thought until the day a wide-eyed half-Mexican third-grader everyone called Papi skated in.

“He used to hang out at my rink all day, pretty much every day,” Whyte said, recalling time he spent with Auston Matthews. “All he wanted to do is get on the ice.”

The Columbus Blue Jackets’ Brendan Gaunce, left, chases the Toronto Maple Leafs’ Auston Matthews across the blue line during the third period of a game on Dec. 29 in Columbus, Ohio.

(Jay LaPrete / Associated Press)

These days Matthews, the top pick in the 2016 NHL draft, gets most of his ice time in Toronto, where the seven-time All-Star has won rookie of the year and most valuable player with the Maple Leafs. This season the All-Star Game MVP leads the league with 49 goals and, heading into Wednesday’s game in Arizona, was on pace to become the first player to finish with 70 in more than three decades.

And that has helped convince Whyte that hockey can bloom anywhere, even in a desert.

“It’s just exposing them to the game, showing them that they’re welcome and hoping that they fall in love with it,” he said. “It’s just a matter of time before this catches on, no matter what color or race or gender.”

Maybe. But for now demographic trends have the NHL and many of its teams focusing intently on the rapidly growing Hispanic market.

About one in five people in the U.S. is Hispanic and together their economic impact grew to $3.2 trillion in 2021, according to the most recent survey by the Latino Donor Collaborative and Wells Fargo. If they formed an independent country, their gross domestic product would rank fifth in the world, ahead of the United Kingdom, France and India.

Yet it’s a market the NHL traditionally has missed. Although 94% of Hispanic males identify as sports fans, the percentage of those who follow the NHL was 6.8%, according to a 2020 poll conducted by FiveThirtyEight and Ipsos. Now, however, the league finds itself well positioned to change that. Forty percent of the NHL’s 32 teams play in the eight states boasting the largest Latino populations, and popularizing the sport in those communities could play a crucial part in helping the league grow.

That’s why the league celebrates Hispanic Heritage Month and why seven teams, including the Kings and Ducks, offer Spanish-language broadcasts, kids’ hockey instruction or bilingual hockey-themed classroom programs, among other things. It’s also why Mexico City is on the short list of potential sites for an NHL game, possibly as soon as next fall.

Matthews, 26, whom the Maple Leafs and NHL declined to make available for this story, is also a big part of that campaign. His mother, Ema, one of eight children, grew up in Hermosillo, Mexico, on a large ranch where Auston, who speaks Spanish, spent many summers. That success and background has opened a path into the Latino community that gives people on both sides of the border a connection to the game they haven’t had.

Anaheim Ducks mascot Wild Wing celebrates on Día de los Muertos night against the Toronto Maple Leafs at Honda Center on Oct. 30, 2022 in Anaheim.

(Debora Robinson / NHLI via Getty Images)

“In Mexico, when people know about him, it inspires people obviously,” said Francisco Rivera, the Spanish-language radio voice of the Kings. “They get excited about having someone that they can probably relate to.”

However the goal isn’t to find the next Auston Matthews, though that might be coming. Instead, it’s simply to introduce hockey to a population that views the sport as more of a curiosity than a passion.

“Fans equal eyeballs and ticket sales. That’s really the key of it,” said Kelly Cheeseman, the chief operating officer for the Kings and AEG Sports, the team’s parent company. “We want to grow our fan base. And knowing that this is one of the bigger audiences [in] Los Angeles, we have to be intentional about how we approach that.”

The Kings have done that by sponsoring youth hockey camps in Mexico, hosting Salvadoran and Mexican heritage nights at Crypto.com Arena, establishing a social media presence and influencer campaign targeted to Latinos and by broadcasting select games on Spanish-language radio. The result has been a 15% rise in the Latino fan base over each of the last three seasons, the team says.

“This is something that we’re really excited about because long term, we know it’s the path ahead,” Cheeseman said. “We have a long, long way to go. We want to be right up there with the Lakers and Dodgers in this town.”

So do the Ducks, who have been active in the Latino community for more than 15 years, sponsoring bilingual hockey-themed educational programs in schools throughout Orange County. The team also has held regular hockey clinics, free skating lessons, a Día de los Muertos–themed night at Honda Center and Spanish-language broadcasts of select games.

Mariachis perform to celebrate Día de Los Muertos night during the second period of a game between the Maple Leafs and the Kings at Crypto.com Arena on Oct. 29, 2022, in Los Angeles.

(Juan Ocampo / NHLI via Getty Images)

“We know what the demographics of our county look like, what they’re trending toward. And we believe that we’ve got the greatest game in the world that we would love to teach to kids,” said Merit Tully, the team’s vice president of marketing. “So we put those resources in the places that aren’t necessarily the most likely to buy hockey tickets right now but have a chance to fall in love with the sport over a lifetime.”

“It’s a win-win,” he added. “We get to introduce our sport to these kids and also be a beneficial part of their education.”

The Dallas Stars, Vegas Golden Knights and Arizona Coyotes also have robust engagement campaigns targeted at Latinos, who make up a large chunk of their local communities.

“You want to be culturally relevant within your marketplace. And in order to do that you have to essentially stay with the times,” said Tully, who has seen the number of Latinos claiming Ducks fandom jump to more than 750,000 in 2022-23, 19% of the team’s total and the second highest of any demographic group.

Matthews’ success has helped with that.

“Without question. Probably in ways that we don’t even see yet,” Tully said. “Here’s a guy that is looking at a record-breaking season. He’s making headlines and getting notoriety in places that we don’t even comprehend. There’s somebody probably in our market that’s looking at him and thinking about the game of hockey for the first time.”

Although the NHL’s Latino initiative is just beginning, its roots run far deeper than Matthews. Current players Max Pacioretty of the Washington Capitals and Matt Nieto of the Pittsburgh Penguins, a Long Beach native, also have Mexican parents. And five men born in Latin America have played in the league (though only Robyn Regehr, who was born in Brazil to Canadian missionaries, appeared in a game after 1990).

Washington Capitals left wing Max Pacioretty (67) skates during the second period of a game on Jan. 3. It was Paciorettys first game as a Capital since re-tearing his right Achilles tendon.

(Susan Walsh / Associated Press)

More recently there has been Scott Gomez, a two-time Stanley Cup champion who retired in 2016 and has Mexican and Colombian parents; Minnesota Wild general manager Bill Guerin, a U.S. Hockey Hall of Famer whose mother grew up in Nicaragua; and Cuban-Colombian goaltender Al Montoya, who played for six teams and is now the director of cultural growth and strategy for the Dallas Stars.

What makes Matthews different, Montoya said, is the fact he’s one of the best players in the league playing for a wealthy, iconic franchise in hockey-mad Canada, where the sport was invented. (Also helpful is the fact he’s never forgotten the days at Ozzie Ice, where he was known as Papi, since the No. 34 sweater he wears in Toronto is in honor of his namesake, David Ortiz — Big Papi — who wore that number in three World Series with the Boston Red Sox.)

“Coming out of Chicago, being raised by a single parent, an immigrant, I didn’t get to go to hockey games. I didn’t think there was a place for me in hockey,” Montoya said. “Seeing that there is a way to be a part of this game is so important. That representation can’t be understated.”

Sam Uisprapassorn, coach of the Colombian national team and part of the Ducks’ Hockey is for Everyone initiative, agreed.

“That definitely goes a long way,” he said. “I remember looking out on the ice and going, ‘Hey, it’s a bunch of white dudes.’ It was like all right, whatever. It is what it is.

“[But] there’s some kid out there that most likely is lacing them up for the first time and I just want them to relate and go, ‘Well heck, I can do that too.’”

Montoya and Uisprapassorn say their immigrant parents encouraged them to become acclimated to living in the U.S. by playing sports — even if those sports were somewhat foreign to them. Montoya remembers how easy it was to find his mom at his youth games because she was the only one cheering in Spanish.

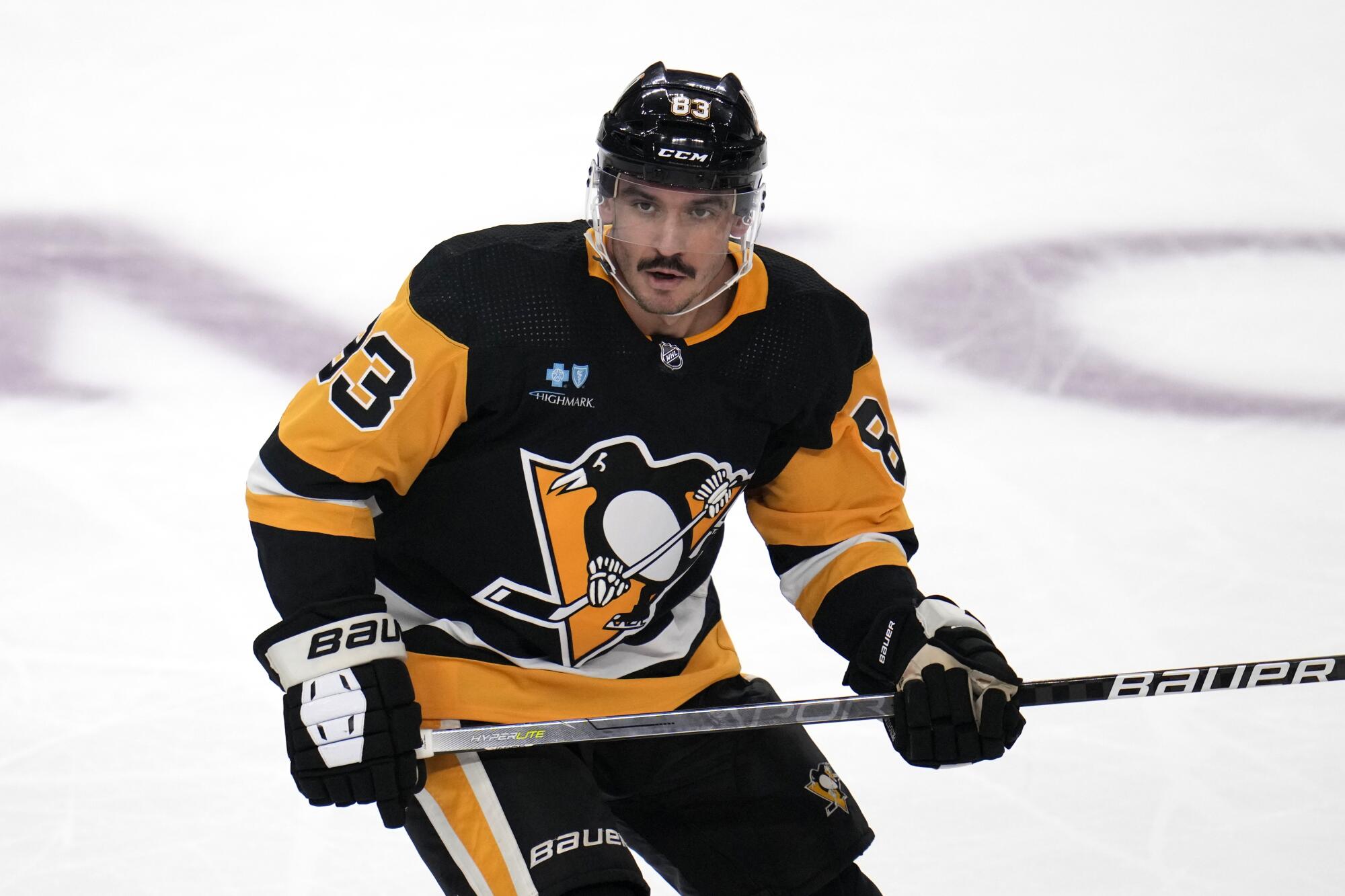

The Pittsburgh Penguins’ Matt Nieto skates during the first period of a preseason game against the Columbus Blue Jackets on Sept. 24.

(Gene J. Puskar / Associated Press)

Now it’s common to hear Spanish spoken at the youth games and clinics he attends in Dallas as part of his job with the Stars, one of five franchises the NHL says has more than a million Latino fans. That’s a number Montoya is sure will grow as the league continues reaching out to the community.

“What we’re doing is making a difference,” he said. “Sport is part of our DNA. I liken it to soccer; ice soccer. We love to celebrate, we love to get our families together. It’s part of our culture.

“And that’s what you can do with a hockey game, bring everyone together.”

But the culture barriers aren’t the only ones keeping hockey out of Latino communities. Several studies have shown that ice hockey is the most expensive team sport for kids under 18, with annual costs topping $2,500. And that doesn’t include the time and expense of traveling to and from often-distant skating rinks for practice and games.

To combat that, the NHL and the NHL Players Assn., through their Industry Growth Fund, have spent more than $180 million during the last decade to bring hockey to underserved communities around North America while individual teams, including the Stars and Ducks, offer free equipment, ice time and hockey lessons in Spanish and English. The Ducks also sponsor a street hockey tournament each year, sending coaches into grade schools to teach kids how to play on the pavement wearing sneakers or in-line skates, easing the need for expensive equipment and ice. (Nieto and former Duck winger Emerson Etem started their careers playing on roller skates in the streets of Long Beach.)

“We have fourth-graders who have been learning the game basically for the entire school year. But their parents haven’t been exposed to hockey at all. They’ve never seen it before,” Tully said. “The kids are so excited to show their parents what they’ve been doing at school and how much fun they’re having.”

The Rangers’ Scott Gomez looks to pass during the second period of a 2009 NHL game against the Sabres at HSBC Arena in Buffalo, N.Y. Gomez was one of the first Latinos to reach the NHL in 1999 and he played 16 season for seven teams, winning the Stanley Cup twice with New Jersey.

(David Duprey / Associated Press)

If any of that inspires a kid to pick up a stick and embrace hockey, and if that passion leads his or her parents to at least accept the game, then it has been worth it.

“Look, with Latinos, I believe we’re the fastest-growing segment of the population,” Uisprapassorn said. “At the end of the day you’ve got to get butts in seats. We need the eyeballs to drive more revenue to keep these teams afloat, to pay player salaries.

“I hate to just take it to the business side of things but at the end of the day that’s really what all of this is. Just think of how much streaming revenue is up for grabs between Mexico to the tip of Argentina.”

Producing another Auston Matthews, meanwhile, would be an unexpected benefit. But as Whyte found out, you can grow the most unexpected things in the desert given the right kind of care.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if sometime we saw a Latin American hockey superstar,” Uisprapassorn continued. “We see the creativity these days from players like [Connor] Bedard or [Connor] McDavid. Just wait to get Latin Americans out on the ice with that level of skill.

“Look at the impact the Latin American players have had on Major League Baseball. Why couldn’t you see that happen?”