Joe Choi stood inside Aladdin Fullerton bookstore, flipping through “Introduction to Business Management” in Korean.

Choi, 33, has lived in the U.S. since he was a teenager, but he’s still more comfortable reading in his native language. He found this out the hard way a few months ago when he picked up Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs.

After looking up lots of words and progressing slowly, Choi got the Korean version of the Jobs book at Aladdin.

On this Friday afternoon, he bought the business management book.

“Coming to this bookstore, I found that you can discover so many different kinds of books when you visit in-person, and even if you can’t find what you’re looking for, the owner can order it straight from Korea,” said Choi.

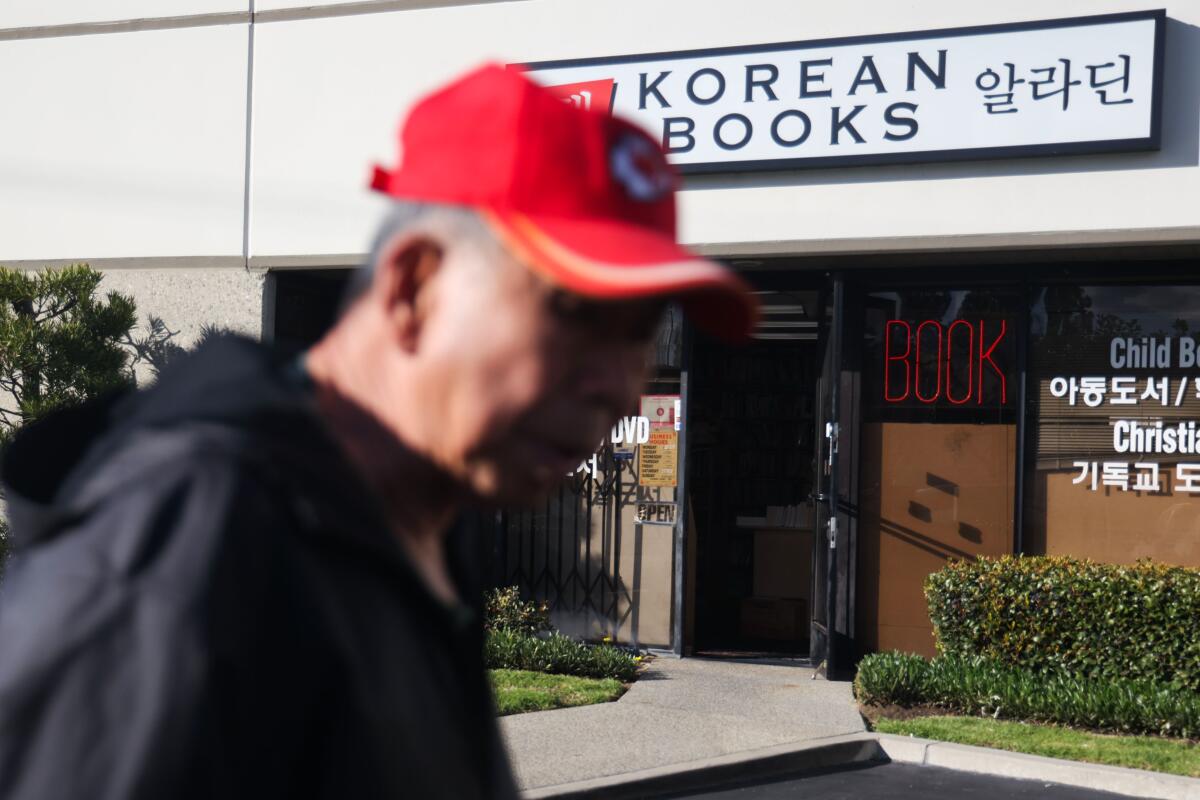

Tucked away in a strip mall in La Mirada, Aladdin Fullerton is one of the last remaining Korean bookstores in Southern California.

Min-woo Nam is the owner of Aladdin Fullerton, one of the last remaining Korean bookstores in Southern California

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

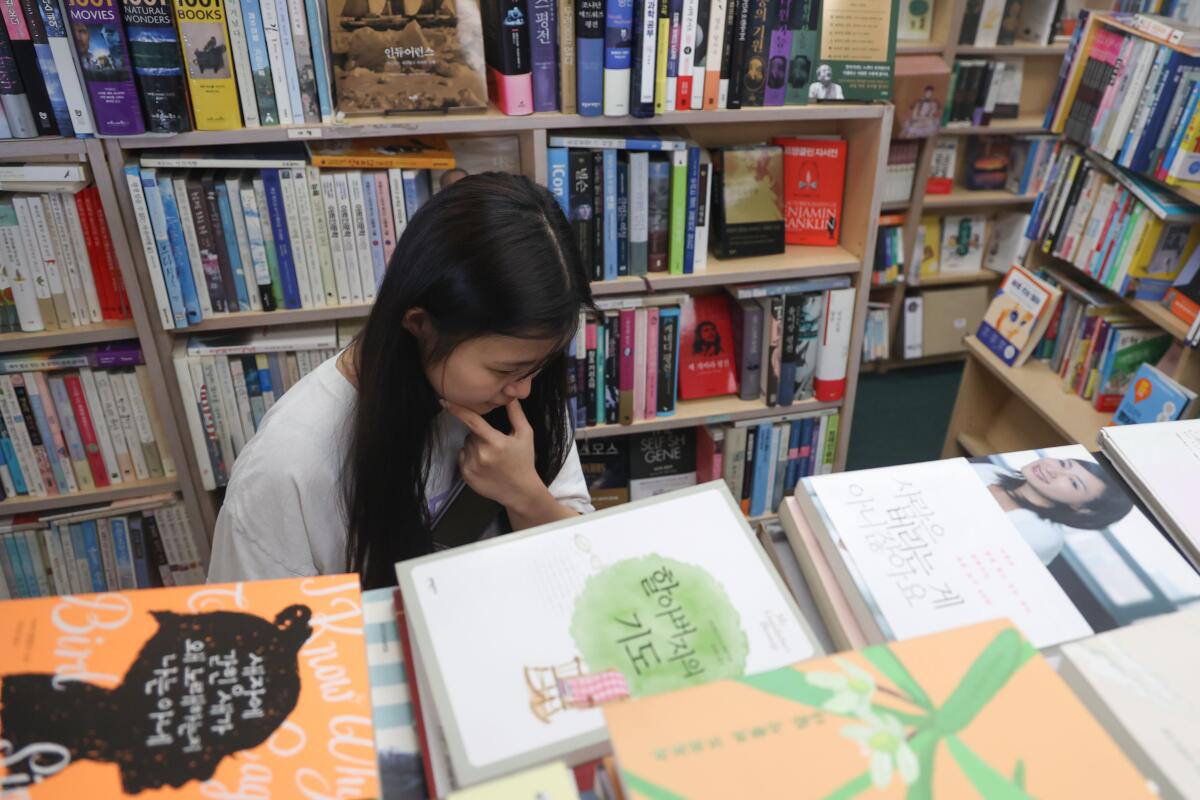

The front table showcases bestselling Korean novels as well as American novels translated into Korean, such as “Crying in H Mart: A Memoir” by Michelle Zauner and “Pachinko” by Min Jin Lee.

The surrounding shelves feature Christian literature, children books, Korean language workbooks, novels, cookbooks and Japanese manga. Old advertisements for churches and tutoring academies are plastered on the sides of the shelves.

Customers range from immigrants like Choi to parents hoping to pass the language to the next generation to non-Koreans trying to learn Korean.

Min-woo Nam said that when he opened Aladdin Fullerton 20 years ago, there were about eight Korean bookstores in Orange County and another dozen in Los Angeles. Now, his store is one of two left in O.C., with about five left in L.A.’s Koreatown.

The struggle of Korean bookstores, serving a relatively small market of Korean speakers and Korean language learners, mirrors that of mainstream bookstores, amid the rise of e-books and online ordering.

Aladdin Fullerton has fewer customers than it did a decade ago. But Nam, who is the store’s sole employee, chooses to look on the bright side. Loyal customers come back again and again. He still makes a profit. And Buena Park’s own growing Koreatown could bring in more business to the store, which is part of a South Korean chain with over a dozen locations in Seoul that can quickly ship just about any book available in Korea. Many of Nam’s customers phone in orders, then stop by to pick them up.

The store offers a “lifetime membership” for a one-time $5 fee that comes with a 25% discount, including on online orders.

“Because most other Korean bookstores have closed, it makes it easier to survive when all my competitors are all but gone now,” said Nam, 66. “It’s all about survival.”

The exterior of the Alladin Fullerton bookstore in La Mirada.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

On a recent Monday afternoon, In-chong Kim arrived to pick up the books that Nam had ordered for him from Korea on topics ranging from Christianity to science.

Kim, who has been shopping at Aladdin Fullerton for over a decade, called the bookstore a slice of home that should live on as a “kind of cultural site for our community.”

Books on a shelf at the Aladdin Fullerton bookstore.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

“This Korean bookstore holds our Korean culture and knowledge in this small space,” said Kim, 65, who is director of the Seoul National University Foundation. “The work the owner is doing here is so special. He doesn’t make much money, but he is keeping a crucial part of our community alive.”

Nam came to the U.S. in 2004 with his wife and two children, opening the bookstore that same year. As an international trader for Samsung, he had worked in Japan and Vietnam for several years, kindling his interest in international affairs and foreign languages.

During slow stretches at the bookstore, he plunges into those subjects. A stack of books on his desk includes a Spanish language workbook, a notebook he uses to practice writing Japanese and a Chinese history book written in Korean.

When shipments from Korea arrive on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, he feels like a little kid opening up a Christmas present, he said.

“I wonder what kind of story this book tells,” he said. “There is not a single boring day here, because I can just read, study and be surrounded by books the entire day.”

Janet Lee, 18, looks for a book at the Aladdin Fullerton bookstore.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

On the Friday that Choi came in, Nam unpacked a box from Korea, pulling out about a dozen books. He verified each one in his online system, meticulously cross-checking with handwritten records in a binder he fills with names, dates, phone numbers and book titles in both English and Korean, decorated with colorful markings legible only to him.

He tacked a sticky note with a customer’s name onto each book. Then, he was ready for the Friday afternoon rush of people picking up their orders.

Fullerton resident John Kim stopped by for a novel by an acquaintance from Korea.

Kim, who works at a construction company, said he doesn’t read much, so he doesn’t come to the store often. Many immigrants, particularly those with young children, don’t have the time or money for reading, he said.

“They’re busy working to put food on the table, so I understand, because when I immigrated here 35 years ago, it was a struggle too,” Kim, 66, said. “So even if we are interested in reading books, oftentimes we can’t afford to.”

A book shipped from Korea can cost around $40, and some customers try to bargain with Nam.

“The price is steeper than I expected,” Sunny Park grumbled as Nam rang up her purchase.

“Ma’am, it is not cheap delivering books all the way from Korea in less than a week,” Nam said firmly.

Nam chats familiarly with many customers, some of whom he’s known for over a decade, sprinkling in casual English words while maintaining some formality through Korean honorifics.

“I’ll enjoy the drink,” Nam said in Korean after Choi dropped by the store again with a Starbucks iced Americano for him. “Thank you!” Nam then called out in English.

For Allie Bell, Aladdin Fullerton is not a piece of home but a portal to a new one.

Bell began studying Korean to better understand her Korean-speaking dance teacher. She also loved Korean food and was interested in the culture.

Only two bookstores — Aladdin Fullerton and Bandi Books in Koreatown — carried

the textbooks required for her Korean class, she said.

Bell, 31, a digital marketer who lives in Cypress, said her Korean isn’t good enough to order online herself. She appreciates coming to the store, where Nam can steer her in the right direction, as he does for other customers who are learning Korean as the rise of Korean pop culture spurs interest in the language.

“So I’m very grateful to the time and effort [Nam] spent making sure I get exactly what I need and providing suggestions that would help me on my language-speaking journey,” she said.

John Kim said that passing the Korean language to the next generation is crucial. And language lives through books.

“Everything from our culture to our history can be found in our language,” he said. “If we don’t have that, our Korean identity will start to unravel, so this bookstore is vital to our community.”