Balloon archways surrounded the stage as the superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District, Alberto Carvalho, last month announced what he hailed as a pioneering use of artificial intelligence in education. It’s a chatbot called “Ed” — an animated talking sun — which he described as: “our nation’s very first AI-powered learning-acceleration platform.”

More than 26 members of local and national media were on hand for the splashy announcement (a detail that Carvalho noted in his remarks), and the event also featured a human dressed in a costume of the shiny animated character of Ed, which has also long been a mascot of the school district, for attendees to take selfies with.

While many publications wrote about the announcement at the nation’s second-largest public school, details about what the $6 million system actually does have been thin. A press release from the LA public school district said that Ed “provides personalized action plans uniquely tailored to each student,” and at one point Carvalho described the system as a “personal assistant.”

But Carvalho and others involved in the project have also taken pains to point out that the AI chatbot doesn’t replace human teachers, human counselors or even the district’s existing learning management system.

“Ed is not a replacement for anything,” Carvalho said at a mainstage presentation this month at the ASU+GSV Summit in San Diego. “It is an enhancement. It will actually create more opportunities and free our teachers and counselors from bureaucracy and allow them to do the social, interactive activity that builds on the promise of public education.”

So what, specifically, does the system do?

EdSurge recently sat down with the developers of the tool, custom-made for the district by Boston-based AI company AllHere, for a demo, to try to find out. And we also talked with edtech experts to try to better understand this new tool and how it compares to other approaches for using AI in education.

A New Tech Layer

In some ways the AI system is an acknowledgement that the hundreds of edtech tools the school district has purchased don’t integrate very well with each other, and that students don’t use many of the features of those tools.

As at many schools these days, students spend much of their learning time on a laptop or an iPad, and they use a variety of tech tools as they move through the school day. In fact, students might use a different online system for every class subject on their schedule, and log into other systems to check their grades or access supplementary resources to help with things like social well-being or college planning.

So LAUSD’s AI chatbot serves as a new layer that sits on top of the other systems the district already pays for, allowing students and parents to ask questions and get answers based on data pulled from many existing tools.

“School systems oftentimes purchase a lot of tools, but those are underutilized,” Joanna Smith-Griffin, chief executive officer at AllHere, told EdSurge. “Typically these tools can only be accessed as independent entities where a student has to go through a different login for each of these tools,” she added. “The first job of Ed was, how do you create one unified learning space that brings together all the digital tools, and that eliminates the high number of clicks that otherwise the student would need to navigate through them all?”

The chatbot can also help students and parents who don’t speak English as their first language by translating information it displays into about 100 different languages, says Smith-Griffin.

But the system does not just sit back and wait for students and parents to ask it questions. A primary goal of Ed is to nudge and motivate students to complete homework and other, optional enrichments. That’s the part of the system leaders are referring to when they say it can “accelerate” learning.

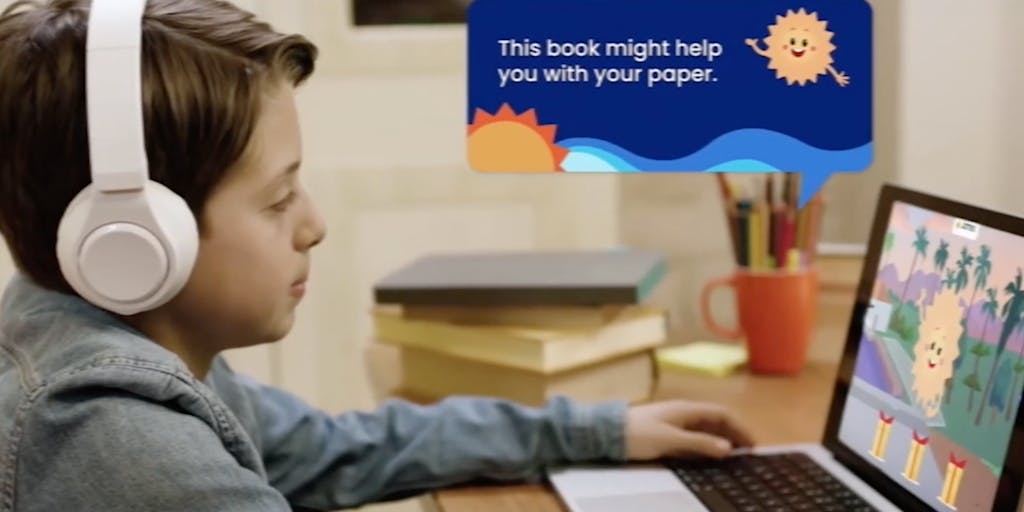

For instance, in a demo for EdSurge, Toby Jackson, chief technology officer at AllHere, showed a sample Ed dashboard screen for a simulated account of a student named “Alberto.” As the student logs in, an animation of the Ed mascot appears, makes a corny joke, and notes that the student has three recommended activities available.

“Nice, now let’s keep it going,” Ed said after a student completed the first task. “And remember, if you stop swimming in the ocean, you’ll sink. Now, why you’re swimming in the middle of the ocean, I have no idea. But the point is, this is no time to stop.”

The tasks Ed surfaces are pulled from the learning management system and other tools that his school is using, and Ed knows what assignments Alberto has due for the next day and what other optional exercises fit his lessons.

The student can click on the activities, which show up in a window that automatically opens, say, a math assignment in IXL, an online system used at many schools.

The hope is that the talking sunburst known as Ed will be relatable to students, and that the experience will “feel like fun,” says Smith-Griffin. Designers tried to borrow tropes from video games, and in the demo, Ed enthusiastically says, “Alberto, you met your goal today,” and points to even more resources he could go to, including links to “Read a book,” “Get tutoring,” or “Find a library near me.” And the designers use two different versions of the digital voice for Ed, depending on the grade level of the student: A higher-pitched, more cartoon-like voice for younger students, and a slightly more serious one for those in middle and high school.

“We want to incentivize daily usage,” says Smith-Griffin. “Kids are excited about keeping their streaks up and stars.”

And she adds that the idea is to use algorithms to make personalized recommendations to each student about what will help his or her learning — the way that Netflix recommends movies based on what a user has watched in the past.

Customer Service?

Of course, most teachers already take pains to make clear to their students what assignments are due, and many teachers, especially in younger grades, employ plenty of human-made strategies like sending newsletters to parents. And learning management systems like Schoology and Seesaw already offer at-a-glance views for students and parents of what is due.

The question is whether a chatbot interface that can pull from a variety of systems will make a difference in usage of school resources.

“It’s basically customer service,” says Rob Nelson, executive director for academic technology and planning at the University of Pennsylvania who writes a newsletter about generative AI and writing.

He described the strategy as “risky,” noting that previous attempts at chatbots for tech support have had mixed results. “This feels like the beginning of a Clippy-level disaster,” he wrote recently, referring to the animated paper clip used by Microsoft in its products starting in the late 1990s, which some users found naggy or distracting. “People don’t want something with a personality,” he added, “they just want the information.”

“My initial thought was why do you need a chatbot to do that?” Nelson told EdSurge in an interview. “It just seems to be presenting links and information that you could already find when you log in.”

As he watched a video recording of the launch event for Ed the chatbot, he said, “it had the feeling of a lot of pomp and circumstance, and a lot of surface hullabaloo.”

His main question for the school district: What metrics are they using to measure whether Ed is worth the investment? “If more people are accessing information because of Ed then maybe that’s a win,” he added.

Officials at LAUSD declined an interview request from EdSurge for this story, though officials sent a statement in response to that question of how they plan to measure success: “It’s too early to derive statistically significant metrics to determine success touch points. We will continue assessing the data and define those KPIs as we learn more.”

Setting Up Guardrails

LAUSD leaders and the designers of Ed stress that they’ve put in guardrails to avoid potential pitfalls of generative AI chatbots. After all, the technology is prone to so-called “hallucinations,” meaning that chatbots sometimes present information that sounds correct but is made-up or wrong.

“The bot is not as open as people may think,” said Jackson, of AllHere. “We run it through filters,” he added, noting that the chatbot is designed to avoid “toxicity.”

That task may not be easy, though.

“These models aren’t very good at keeping up with the latest slang,” he acknowledged. “So we get a human being involved to make that determination” if an interaction is in doubt. Moderators monitor the software, he says, and they can see a dashboard where interactions are coded red if they need to be reviewed right away. “Even the green ones, we review,” he said.

So far the system has been rolled out in a soft launch to about 55,000 students from 100 schools in the district, and officials say they’ve had no reports of misconduct by the chatbot.

Leaders at AllHere, which grew out of a project at Harvard University’s education school in 2016, said they’ve found that in some cases, students and parents feel more comfortable asking difficult or personal questions to a chatbot than to a human teacher or counselor. And If someone confides to Ed that they are experiencing food insecurity, for instance, they might be connected to an appropriate school official to connect them to resources.

An Emerging Category

The idea of a chatbot like Ed is not completely new. Some colleges have been experimenting with chatbot interfaces to help their students navigate various campus resources for a few years.

The challenge for using the approach in a K-12 setting will be making sure all the data being fed to students by the chatbot is up-to-date and accurate, says James Wiley, a vice president at the education market research firm ListEdTech. If the chatbot is going to recommend that students do certain tasks or consult certain resources, he adds, it’s important to make sure the recommendations aren’t drawing from student profiles that are incomplete.

And because chatbots are a black box as far as knowing what text they will generate next, he adds, “If I have AI there, I might not see the errors [in the data] because the layer is opaque.”

He said officials at the school district should develop some kind of “governance model” to evaluate and check the data in its systems.

“The stakes here are going to be pretty high if you get it wrong,” he says.

Whether this type of system catches on at other schools or at colleges remains to be seen. One challenge, Wiley says, is that at many educational institutions, no one is in charge of the student and parent experience. So it’s not always clear whether a tech official would lead the effort, or perhaps, in a college setting, someone leading enrollment.

In the end, Wiley says the Ed chatbot is hard to quickly describe (he opted to say it’s an “engagement and personalization layer between systems and students.”)

If done right, “it could be more than just a gimmick,” he says, creating a tool that does what Waze achieves for drivers trying to find the best route on a road, only for getting through school or college.