The battle between Myanmar’s military and rebel groups for control of the southeastern border town of Myawaddy has seen thousands of refugees cross into neighboring Thailand in April.

But while many return to Myanmar when there is a lull in the fighting, others are seeking a more permanent escape from the conflict.

Myanmar is experiencing a critical time during its over three-year-long post-coup conflict with rebel groups gaining significant territory and launching unprecedented attacks on the Myanmar regime.

Armed ethnic groups have captured bases in northern Shan state and Rakhine state since October.

The most significant success came via the Karen National Union, or KNU, who earlier in April announced it had forced the surrender of hundreds of Myanmar’s military soldiers who had been in control of Myawaddy.

The junta have since regained a foothold by occupying a base in Myawaddy, but are still fighting to retain full control from the KNU and its allies.

Local media report that junta reinforcements were advancing on Myawaddy as of Monday evening.

The border town connects billions of dollars’ worth of trade passing between Myanmar and Thailand each year.

Saw Thoo Kwei is a small business owner in Myawaddy. He said the situation in the town has deteriorated since the recent conflict.

“During a particularly intense period of conflict, I found myself having to seek refuge near the border in Myanmar for one night,” he told VOA. “As the situation gradually cooled down, I returned home. [But] I can’t stay here long because of the conflict,” he added.

The 30-year-old owns a grocery store in Myawaddy, but the weeks of fighting between government troops and rebels have affected everyday life in the town.

“Currently, there is no policing in Myawaddy, not even traffic police. Most government offices are closed. There is no fighting in the city, but people are living in fear. Many civilians are worried about heavy artillery like mortar shells,” he said.

His business is also suffering from the uncertainty, which has prompted Saw Thoo Kwei to make plans to leave Myanmar.

“Small businesses don’t have many stocks to sell due to road blockages. The fighting in Myawaddy has really hit our business hard. We’re seeing fewer customers, which means sales are down, and sometimes we have to shut the shop.

“With the power cuts and prices shooting up, it’s getting tough. We have to worry about thieves targeting our shop when things get tense, showing how unsafe Myawaddy can be. My only viable option is to relocate to Thailand,” he said.

Since April, the fighting has continued despite the KNU announcing its forces had retreated from one base in the town. The tussle for control of Myawaddy led to at least 1,300 refugees crossing from Myanmar into Thailand, The Associated Press reported on April 20, citing Thai officials.

But that number may be higher as volunteers aiding the refugees told Myanmar Now that 3,000 were returned to Myanmar when fighting in the border town had temporarily quietened.

Thailand shares a 2,400-km (1491-mi) -long land border with Myanmar.

Thailand’s border town Mae Sot, which sits across the Moei river from Myawaddy, has long been accustomed to receiving thousands of people from Myanmar, with many fleeing the war.

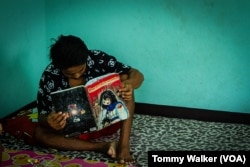

In one undisclosed safehouse in Mae Sot, nearly a dozen Myanmar refugees have fled the conflict in recent weeks.

Kyaw Zin Oo, a physics teacher from the Ayeyarwady region, told VOA he needed to leave Myanmar to avoid being conscripted by the junta.

“I arrived here 17 days ago. I had two choices, to go with the [Myanmar military] or here. I chose to come to Thailand because I see more of a future here. I have friends who have joined the revolution. I thought about joining but I thought I can still support them from here by donations and sending food to them.”

Other refugees, who didn’t want to be identified, said they left Myanmar because the junta had targeted them and their family because of their participation in anti-military protests.

Myanmar’s military enacted a conscription law in February that makes 14 million men and women eligible to be drafted into the military and says it will conscript up to 60,000 new recruits a year. The Irrawaddy reports that the military has begun recruiting Rohingya people despite the ethnic minority group suffering appalling atrocities by Myanmar’s military in 2017.

The junta is looking to bolster its ranks so it can resist the momentum gained by rebel groups in recent months.

Chi Lin Ko, a farm worker from Yangon, sits in a bamboo-crafted hut in a highway lay-by in Mae Sot, pondering his next move. The 19-year-old farm worker left Myanmar over a month ago.

But the prospect of fighting for the military spooked him.

“I received a [military conscription] pamphlet at my home. My neighbors joined, but I came here because I didn’t want to join the military. I’ve heard there is a paid salary, but by enlisting in the military there’s no way I can leave after I’ve joined,” he said.

If Chit Lin Ko were to ever pick up arms, it wouldn’t be for the Tatmadaw. “If I didn’t have any family, I would go and fight with the revolutionary groups,” he said.

One of the reasons the teenager left Myanmar was to financially support his family. Myanmar’s conflict has devastated the country’s economy, which is 10% lower than it was in 2019, according to a December report by the World Bank.

“I have a family and need to look after to them, so I need to make money,” Chit Lin Ko said.

The U.N. says at least 45,000 Myanmar refugees have entered Thailand since the military coup over three years ago.

Although Thailand’s government has recently pledged to welcome “100,000” Myanmar refugees, Thailand is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and has no specific domestic legal framework for the protection of urban refugees and asylum-seekers.

Since the military seized power in Myanmar, nearly 5,000 people have been killed and over 26,000 people arrested, according to rights groups.