Lebanon’s Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, who Israel said on Saturday it has killed, has led Hezbollah through decades of conflict with Israel, overseeing its transformation into a military force with regional sway and becoming one of the most prominent Arab figures in generations — with Iranian backing.

The Iran-backed Hezbollah has yet to issue any statement on the status of Nasrallah, who has led the group for 32 years.

The Israeli military said it killed Nasrallah in an airstrike on the group’s central headquarters in the southern suburbs of Beirut a day earlier.

The Israeli military “eliminated … Hassan Nasrallah, leader of the Hezbollah terrorist organization,” Israeli army spokesperson Avichay Adraee wrote in a statement on X.

If the Israeli claim of his death is confirmed by Hezbollah, Nasrallah will be remembered among his supporters for standing up to Israel and defying the United States. To enemies, he has been the head of a terrorist organization and a proxy for Iran’s Shi’ite Islamist theocracy in its tussle for influence in the Middle East.

His regional influence has been on display over nearly a year of conflict ignited by the Gaza war, as Hezbollah entered the fray by firing on Israel from southern Lebanon in support of its Palestinian ally Hamas.

Yemeni and Iraqi groups followed suit, operating under the umbrella of “The Axis of Resistance.”

“We are facing a great battle,” Nasrallah said in an August 1 speech at the funeral of Hezbollah’s top military commander, Fuad Shukr, who was killed in an Israeli strike on the Hezbollah-controlled southern suburbs of Beirut.

Yet when thousands of Hezbollah members were injured and dozens killed as their communications devices exploded in an apparent Israeli attack last week, that battle began to turn against his group.

Responding to the attacks on Hezbollah’s communications network in a September 19 speech, Nasrallah vowed to punish Israel.

“This is a reckoning that will come, its nature, its size, how and where? This is certainly what we will keep to ourselves and in the narrowest circle even within ourselves,” he said.

He has not given a broadcast address since then.

Israel has meanwhile dramatically escalated its attacks, killing several senior Hezbollah commanders in targeted strikes and unleashing a massive bombardment in Hezbollah-controlled areas of Lebanon, which has killed hundreds of people.

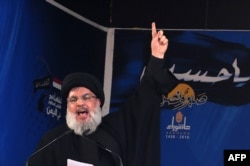

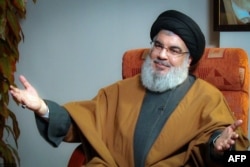

Recognized even by his enemies as a skilled orator, Nasrallah’s speeches are followed by friend and foe alike.

Wearing the black turban of a sayyed, or a descendent of the Prophet Mohammad, Nasrallah uses his addresses to rally Hezbollah’s base but also to deliver carefully calibrated threats, often wagging his finger as he does so.

He became secretary general of Hezbollah in 1992 at age 35, the public face of a once shadowy group founded by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards in 1982 to fight Israeli occupation forces.

Israel killed his predecessor, Sayyed Abbas al-Musawi, in a helicopter attack. Nasrallah led Hezbollah when its guerrillas finally drove Israeli forces from southern Lebanon in 2000, ending an 18-year occupation.

‘Divine victory’

Conflict with Israel has largely defined his leadership. He declared “divine victory” in 2006 after Hezbollah waged 34 days of war with Israel, winning the respect of many ordinary Arabs who had grown up watching Israel defeat their armies.

But he became an increasingly divisive figure in Lebanon and the wider Arab world as Hezbollah’s area of operations widened to Syria and beyond, reflecting an intensifying conflict between Shi’ite Iran and U.S.-allied Sunni Arab monarchies in the Gulf.

While Nasrallah painted Hezbollah’s engagement in Syria — where it fought in support of President Bashar al-Assad during the civil war — as a campaign against jihadists, critics accused the group of becoming part of a regional sectarian conflict.

At home, Nasrallah’s critics said Hezbollah’s regional adventurism imposed an unbearable price on Lebanon, leading once friendly Gulf Arabs to shun the country — a factor that contributed to its 2019 financial collapse.

In the years following the 2006 war, Nasrallah walked a tightrope over a new conflict with Israel, hoarding Iranian rockets in a carefully measured contest of threat and counterthreat.

The Gaza war, ignited by the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel, prompted Hezbollah’s worst conflict with Israel since 2006, costing the group hundreds of its fighters, including top commanders.

After years of entanglements elsewhere, the conflict put renewed focus on Hezbollah’s historic struggle with Israel.

“We are here paying the price for our front of support for Gaza, and for the Palestinian people, and our adoption of the Palestinian cause,” Nasrallah said in the August 1 speech.

Nasrallah grew up in Beirut’s impoverished Karantina district. His family hails from Bazouriyeh, a village in the Lebanon’s predominantly Shi’ite south, which today forms Hezbollah’s political heartland.

He was part of a generation of young Lebanese Shi’ites whose political outlook was shaped by Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Before leading the group, he used to spend nights with frontline guerrillas fighting Israel’s occupying army. His teenage son, Hadi, died in battle in 1997, a loss that gave him legitimacy among his core Shi’ite constituency in Lebanon.

Powerful enemies

He has had a track record of threatening powerful enemies.

As regional tensions escalated after the eruption of the Gaza war, Nasrallah issued a thinly veiled warning to U.S. warships in the Mediterranean, telling them: “We have prepared for the fleets with which you threaten us.”

In 2020, Nasrallah vowed that U.S. soldiers would leave the region in coffins after a U.S. drone strike in Iraq killed Iranian General Qassem Soleimani.

He expressed fierce opposition to Saudi Arabia over its armed intervention in Yemen, where, with U.S. and other allied support, Riyadh sought to roll back the Iran-aligned Houthis.

As regional tensions rose in 2019 following an attack on Saudi oil facilities, he said Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates should halt the Yemen war to protect themselves.

“Don’t bet on a war against Iran because they will destroy you,” he said in a message directed at Riyadh.

On Nasrallah’s watch, Hezbollah has also clashed with adversaries at home in Lebanon.

In 2008, he accused the Lebanese government — backed at the time by the West and Saudi Arabia — of declaring war by moving to ban his group’s internal communication network. Nasrallah vowed to “cut off the hand” that tried to dismantle it.

It prompted four days of civil war pitting Hezbollah against Sunni and Druze fighters. The Shi’ite group took over half the capital, Beirut.

He strongly denied any Hezbollah involvement in the 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik al-Hariri, after a U.N.-backed tribunal indicted four members of the group.

Nasrallah rejected the tribunal — which in 2020 eventually convicted three of them in absentia over the assassination — as a tool in the hands of Hezbollah’s enemies.