Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Good morning. Yelp sued Google yesterday, claiming that the search giant had prioritised its own reviews over Yelp’s, in violation of antitrust law. Here at Unhedged, we value all reviews equally. Send us yours: robert.armstrong@ft.com and aiden.reiter@ft.com.

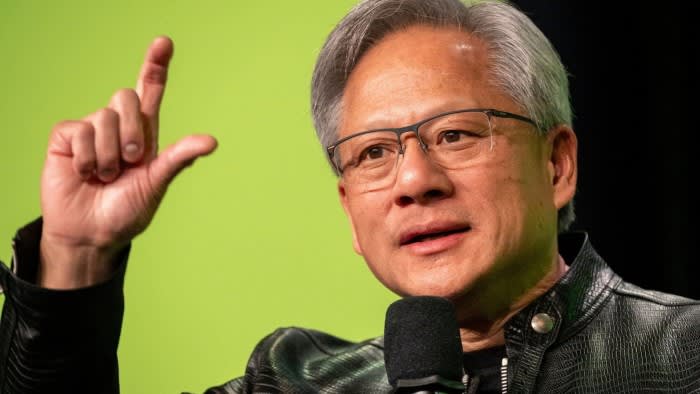

Nvidia

It looks like we may have gotten away with it.

Nvidia is a $3.1tn company, and the stock has had an 800 per cent run in two years. It is 6 per cent of the S&P 500, which understates its totemic significance as the centrepiece of the AI trade. Consensus estimates for its quarterly earnings, which landed yesterday afternoon, were for revenues to increase 115 per cent. This understates what the market was really hoping for — probably by a lot. On the basis of (high) expectations for next year’s earnings, the shares trade at a premium to the market of about a third. All of this is fairly frightening from a market stability point of view.

In the event, Nvidia’s quarterly growth was 120 per cent, and the stock only fell by a non-catastrophic 6 per cent in late trading. The other Magnificent 7 tech stocks took the news in stride. Take a little sigh of relief, everyone. This could have been a lot worse. We just need the market to keep its nerve today.

If it does — a non-trivial if — the significance of this report may be that it put the final stamp on a big change in market leadership. If 120 per cent revenue growth cannot even keep Nvidia’s shares flat, it is a bit hard to see how the company and its big peers can continue to lead the market higher, as they have for much of the past few years. Big Tech’s growth has been very good, but at current prices, good isn’t good enough. Unless growth re-accelerates, leadership may have to come from somewhere else.

The regime change has been under way since Nvidia peaked on June 18. Since then, tech has been a drag on the broader market, while falling interest rate plays like real estate, utilities and financials, as well as defensives such as healthcare and consumer staples, have stood out:

The Mag 7 stocks have mostly underperformed the SPX since June 18. Only Tesla (which had been beaten up), Meta (relatively cheap) and Apple (a straight-up defensive stock at this point) came out ahead:

Options investors caught wind of this change. The put call ratio, which had been tilted towards calls, has been about even since June:

Regime change is probably healthy, if no one gets hurt in the transition. Overreliance on one narrative can cause instability. It’s not clear what regime is supplanting tech and AI, though. Small caps and value stocks have both beaten the S&P 500 since June, and the S&P equal weight outperformed the S&P. But growth stocks underperformed, dragged down by tech:

We are excited to see who comes out on top.

(Armstrong and Reiter)

Greedflation: the big questions

This week I’ve written a few pieces about greedflation. I’ve tried to stick to a narrow corporate finance question: did the post-pandemic inflation provide a real profit boost for very large grocery retailers, branded foodmakers and consumer goods companies? I’ve tried to avoid economic and ethical questions: how much of the post-pandemic inflation was caused by higher corporate profits? Were post-pandemic price increases unethical, or something we should regulate?

When it comes to inflation, however, the big questions just will not leave a guy alone. Isabella Weber, a well-known economist at the University of Massachusetts, shared a chart on X and some words from one of this week’s letters, and a lot of people reposted it. Weber is the author of a famous paper arguing that “the US Covid-19 inflation is predominantly a sellers’ inflation” driven by co-ordinated price increases, and she also thinks price controls are a good policy response after economic shocks.

The reposts have sort of put me, at least on X, into the “greedflation is bad and should be regulated” camp. But I’m not. What follows are some things I think we can say about the big questions, from a corporate finance/common sense point of view.

Some big companies in the food value chain saw a big increase in nominal profits during the post-pandemic inflation, and that increase was driven mostly by price increases. Mondelez is a pretty clear example here, as we noted yesterday. Here is the company’s operating profits over the past 13 years:

The years 2021-23 were very profitable for Mondelez, but cookie and cracker sales volumes only rose by a few percentage points. Nor were there big breakthroughs on costs. What happened was a company that had been growing in the low single digits became a double-digit grower because it took price increases, and a lot of the resulting revenue became profit. And to repeat: for the industry in general, this was not about margins, but about additional dollars of profit. Margins on sales are a distraction in the greedflation discussion.

In real terms, the higher profit is a bit harder to interpret. In the 2021-23 period, Mondelez’s nominal operating profit was about 28 per cent higher than in 2019 (which was a good year). But CPI prices generally are up about 20 per cent since the start of the pandemic. And no one begrudges a food company using price to keep its inflation-adjusted profits flat (do they?). Mondelez also would likely have had some profit growth were it not for inflation and pricing. So how much extra profit are we talking about here — and how much would be too much, if there is such a thing as too much? It’s not clear to me.

It matters whether price increases were possible because of excess demand or because of limited supply. If Mondelez could charge more because people had more money and were therefore willing to pay more for Oreos, that does not seem like the sort of thing we should regulate. But if there was a shortage of cookies because of the pandemic, it’s not as clear. I don’t know what the supply shock/demand shock balance was for the food industry. But there is an interesting possible wrinkle here. Yesterday Francesco Franzoni of the University of Lugano sent me a paper he co-wrote. It argues that when supply chains are disrupted, bigger firms are affected less than smaller ones, because they have more diversified supply chains and more bargaining power (we have heard industry analysts make a similar claim). This, Franzoni argues, lets the big companies mark up prices and take market share at the same time. Industry concentration may be inflationary under supply chocks.

It matters whether the price-driven higher real profits get competed away. I just can’t get that excited about companies making some extra money for a year or two after a big economic shock, if competition pushes the economic relationships back to normal in time. We seem to be seeing competition come back strong, for example, in fast food. If it doesn’t happen in grocery soon, then there is something wrong with the structure of the market that regulators should look at. But I don’t think we can conclude quite yet that competition has failed.

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.