For two days in the fall of 2022, Danny Lyon was transported back to his distant biker past. The celebrated photographer was in Cincinnati visiting the movie set of “The Bikeriders,” a drama based on his 1968 book of photographs and interviews that documented the early years of an outlaw motorcycle club.

The production re-created the gang’s rough-edged clubhouse in a corner bar, where writer-director Jeff Nichols was setting up a shot. And parked right outside was a row of vintage motorcycles, including one that looked just like Lyon’s old 650cc Triumph. Lyon hadn’t ridden one in years.

“So I get on the motorcycle and it feels really good,” recalls Lyon. “I look down and there’s a little key next to the oil tank. And I go, ‘Oh, I wonder if it starts?’” Lyon then turned the key and tried to kick-start the ancient machine to life. “It starts and it goes off like a World War I artillery barrage, it’s so noisy. A hundred people turn around and stare at me.

“Oh, I wanted to go so bad,” Lyon, 82, says with a laugh, on the phone from his home in New Mexico. “I just wanted to ride around the corner like I used to when I was 25.”

Nichols, who had dreamed of translating Lyon’s book into a film for two decades and was in the middle of a tight 41-day shoot, remembers the moment. “My producer literally almost jumped out of her shoes trying to stop him,” recalls Nichols. “Danny is such an instigator or a rebel. It was exciting and also terrifying to watch an 80-year-old man do that.”

Austin Butler, right, in the movie “The Bikeriders.”

(Kyle Kaplan / Focus Features)

Lyon and the production survived his two days on set. “The Bikeriders” opens Friday as a highly anticipated feature film starring Austin Butler, Jodie Comer and Tom Hardy, after earning rave reviews at Telluride last year. Its release was delayed by the SAG-AFTRA strike, since the actors would be unable to promote the film, and it was dropped from the Disney calendar, which led producer New Regency to find a new distributor in Focus Features.

It tells a tough but romantic story of the motorcycle club Lyon joined and documented in the mid-1960s on the north side of Chicago, with vivid moments of camaraderie and brutal scenes on the highway. They were a group of young Americans rejecting mainstream society, and for two years Lyon wore the colors as a full member of the Outlaws Motorcycle Club. (The club is called the Vandals in the movie.)

“It’s really about these blue-collar guys who loved motorcycles and loved each other, and there were amazing people among them,” Lyon says. “Those were the guys I tried to make the book about. And they looked great too.”

The project came after more serious work: Lyon had spent time in the Mississippi Delta documenting the civil rights movement while an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, when he was the roommate of activist and future Congressman John Lewis. Later, he would spend nearly two years inside Texas prisons to document the lives and conditions there, immersive photography that has been described as the visual equivalent of the era’s New Journalism popularized by the likes of Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe.

Lyon ultimately joined the esteemed Magnum photo agency and lived for a time with photographer Robert Frank. He rarely took outside assignments, but spent two weeks shooting still photos in Death Valley on the set of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film “Zabriskie Point,” and for three days in 1970 he photographed Muhammad Ali training in Miami for the Sunday Times in London. That same year, he left New York for New Mexico and built a house there, where he’s been based ever since. It’s a life story he recounts in a new memoir, “This is My Life I’m Talking About.”

“The Bikeriders” remains his best-known work, which took its final shape after a book editor in New York advised Lyon that he needed some significant text to accompany the pictures. The photographer returned to Chicago with a portable reel-to-reel recorder to capture the voices and stories behind the black-and-white images. Lyon rode and partied with the Outlaws, but remained committed to his work.

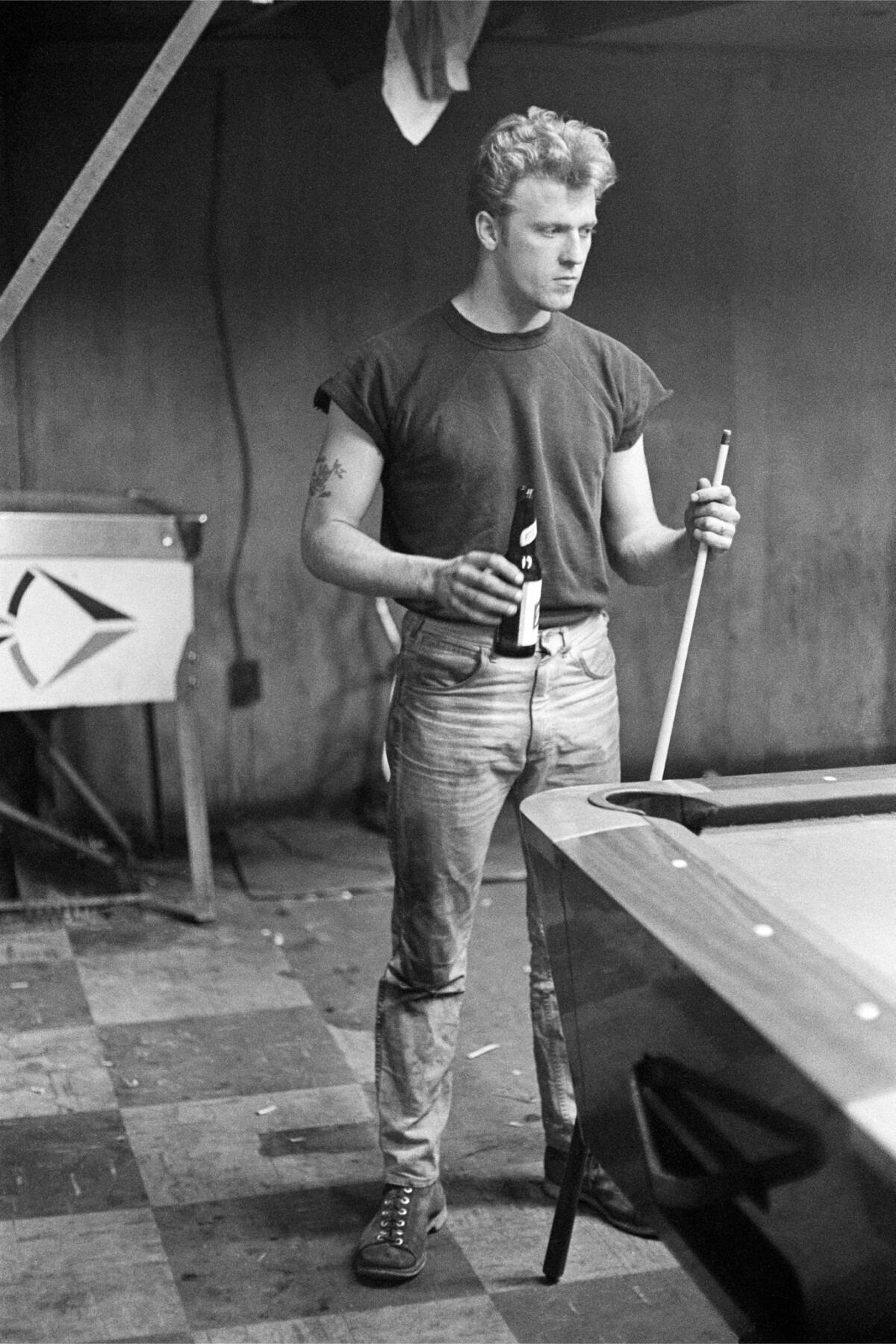

The real-life Benny Bauer, the 19-year-old Chicago Outlaw member, photographed by Danny Lyon for the book that would become “The Bikeriders.”

(Danny Lyon)

“If you want to take photographs — I’m just speaking for myself — you shouldn’t be drunk. You shouldn’t be too stoned. You shouldn’t crash your motorcycle. And you should get it in focus, develop the film and you can’t really be a [screw] up,” Lyon advises.

“I wanted to be an artist. I’m a college graduate. Of course, I did this for all the intellectual reasons. But as time has gone by and I have aged, I think I did it for the adventure,” he admits. “These guys were all semi-nuts, but they rode motorcycles. I went on these runs with them. The excitement was incredible.”

Director Nichols was about 25 when he first saw a copy of “The Bikeriders” in the Memphis apartment of his older brother, Ben, of the indie-rock band Lucero. A couple of years later, the singer-guitarist released a song of the same name, growling urgent lyrics seemingly torn from the book’s pages: “Kathy’s been with Benny Bauer ever since that night … She’s seen more jails and courts and lawyers than she’d like to say.”

As a budding filmmaker, the younger Nichols brother also saw cinematic possibilities in the book’s pictures and interviews. Several of the book’s most distinctive images are visually re-created in the film.

“It is kind of incredible just how much Danny got these people to talk and unburden themselves with their stories,” says the 45-year-old Nichols, an independent filmmaker born and raised in Little Rock, Ark., acclaimed for a series of dramatic features largely focused on the American South, including “Take Shelter,” “Mud” and “Loving.”

Mike Faist, left, and director Jeff Nichols on the set of “The Bikeriders.”

(Kyle Kaplan / Focus Features)

“Their stories start to get complicated. They’re pretty unvarnished, sometimes cruel, sometimes hilarious.”

The copy of “The Bikeriders” Nichols first saw was a later edition, and included several color photographs previously unpublished. He found the additions essential to finding the story for his film, as it offered additional texture and a new introduction by Lyon that explored what happened to some of the people he’d photographed years before.

The story of the motorcycle club turned much darker by the early ’70s, after Lyon moved onto other subjects. As depicted in the film, the anti-establishment club evolved into an organized criminal gang and left many casualties behind.

Filmmakers had come around before with ideas to film “The Bikeriders,” but Nichols was the first to option the book officially. Unlike his past projects, Nichols didn’t sketch out an outline before writing the script. He instead slowly built the world of these motorcyclists from moments and disconnected experiences, before hooking into a bleaker plot in the second half of the film.

“I wanted the first hour to really flow and not out of a particular narrative,” says Nichols, who also learned to ride a motorcycle during the writing process, “because I didn’t want to be a complete fraud.”

Playing a version of Lyon in the film is actor Mike Faist, who had just completed his work in Luca Guadagnino’s tennis three-way “Challengers” when he was approached by Nichols. After working on the acclaimed, intensely emotional movie, Faist planned to decompress for the remainder of the year, but was drawn both to the material and the caliber of actors Nichols was signing up.

“Truthfully, it was really nice to shed ‘Challengers,’ as fulfilling an experience as that was,” Faist, 32, says during a Zoom interview. “I was really spent and I had given a lot. … I felt as if ‘Bikeriders’ was a gift to Mike the actor to be reinspired by watching all of these amazing people do their work.”

He also found inspiration in the example of Lyon. Faist came up to his cabin in Maine, where Lyon showed the actor how to use the Nikon F-model camera. They also did some fishing while the actor learned of Lyon’s deep history as a still photographer and independent filmmaker.

“He really has a soft spot for people that are just shunned from society, that are outcasts, that are told that they’re not allowed a seat at the table,” says Faist. “He really loves these people.”

Jodie Comer and Austin Butler in director Jeff Nichols’ “The Bikeriders.”

(Kyle Kaplan / Focus Features)

Lyon was equally impressed with the film’s authenticity, which lacks the nostalgic glow of so many period films, but remains gritty and vital. For one, he is amazed how Comer so vividly re-created the distinctive Chicago accent of Kathy, wife of the young biker “Benny” (Butler). Lyon remembers Kathy as “a brilliant speaker — she was an absolute riot.”

In one scene from the film, Kathy is talking to Faist’s Danny about the contradictions of biker culture, as she folds laundry: “With all of these guys, none of them could follow a rule to save their life, you know?… You put them together and they get in this club and all of a sudden they make up all these rules for everybody to follow. It’s absolutely ridiculous, you know?”

One of the most memorable bikers depicted in the film is Zipco, a Latvian immigrant Lyon once interviewed at length while he was laid up in the hospital after a drunken riding accident. An excerpt from the book is re-created in a scene as Zipco angrily laments being rejected by the Army.

A lumbering presence in black leather, ragged hair and a layer of grime, Zipco is played by Nichols regular Michael Shannon, who “is absolutely amazing,” says Lyon. “He looks like Zipco, he drools like Zipco — this guy smells like Zipco. And he’s talking to the so-called photographer, who is like a bug to him.”

“Jeff took the book and turned it into this movie, which is a huge accomplishment,” says Lyon, still marveling. Earlier this week, Lyon attended the premiere at the TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood and posted a picture on Instagram of Butler on the red carpet and wrote: “What began in Hyde Park, Chicago 1965. Crazy.”

But “The Bikeriders” is just one chapter of an eventful life. Lyon’s time chronicling the Texas prison system, traveling through South America, and many other adventures might seem just as ripe for potential transition to the screen. It hasn’t gone unnoticed.

“I actually thought about it,” Nichols says. “I haven’t really pursued it, but it’d make an incredible series. His story is remarkable.”