Robert Towne, the screenwriting icon who won an Academy Award for his original script for “Chinatown,” died Monday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 89.

His publicist Carri McClure announced the news on Tuesday.

In a screenwriting career launched in 1960 as a writer for low-budget producer-director Roger Corman, Towne earned an early reputation in Hollywood as a sought-after “script doctor,” stepping in to do uncredited work on troubled screenplays for movies such as “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967) and “The Godfather” (1972).

Towne had yet to become a legend of the New Hollywood era of filmmaking when he saw a 1969 photo essay in West, the Los Angeles Times’ old Sunday magazine.

Titled “Raymond Chandler’s L.A.,” it featured recently shot photographs of Los Angeles locales taken as if it were still the late 1930s and ‘40s heyday of Chandler’s fictional hard-boiled private eye Philip Marlowe, including an evocative photo of a vintage convertible parked next to an old streetlight outside Bullocks Wilshire, the landmark Art Deco luxury department store on Wilshire Boulevard.

Towne, a Los Angeles native born during the Depression, said in a 2008 Writers Guild Foundation interview that he was amazed that “you could still recapture the L.A. that I vaguely remembered by the judicious selection of locations around the city, many of which I knew.”

“That got me started thinking.”

Indeed, Towne often acknowledged that the photo essay was a catalyst for writing the critically acclaimed, influential screenplay for which he is best known: “Chinatown.”

Directed by Roman Polanski and starring Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway, the 1974 film classic is set in 1937 Los Angeles and features Nicholson as private investigator J.J. “Jake” Gittes, who is hired to investigate a supposedly cheating husband but instead finds himself enmeshed in a dark mystery involving deception, murder, and a vast water and land conspiracy in the San Fernando Valley.

Towne received rare public acknowledgment of his behind-the-scenes work in 1973 when “Godfather” director Francis Ford Coppola accepted a screenwriting Oscar for that landmark film and, “giving credit where credit is due,” thanked him for writing “the very beautiful scene between Marlon [Brando] and Al Pacino in the garden” — a scene Towne wrote the night before it was shot that illustrates the transfer of power from the aged Mafia don to his son Michael and indirectly captures the love between the two characters.

Hawk Koch, left, Robert Evans and Robert Towne at a 30th anniversary screening of “Chinatown” in 2004.

(Mark J. Terrill / Associated Press)

Two years later, the press was calling Towne “the hottest writer in Hollywood.”

Bookending his Academy Award-winning script for “Chinatown” were Oscar nominations for his screen adaptation of the novel “The Last Detail” (1973), starring Nicholson as one of two Navy lifers escorting a young prisoner to Portsmouth Naval Prison; and for “Shampoo” (1975), which he co-wrote with the film’s producer, Warren Beatty, who starred as a womanizing Beverly Hills hairdresser.

Among Towne’s other screenwriting credits are “The Yakuza” (with Paul Schrader), “The Two Jakes” (a “Chinatown” sequel), “Days of Thunder,” “The Firm,” (with David Rabe and David Rayfiel), “Mission: Impossible” (with David Koepp) and “Mission Impossible: II.” As a frequent script doctor, he also did uncredited work on films such as “Drive, He Said,” “The Parallax View,” “Marathon Man,” “The Missouri Breaks” and “Heaven Can Wait.”

The tall, bearded and soft-spoken screenwriter who favored slim cigars became a director with the 1982 film “Personal Best,” from his original screenplay about two female track stars. He later directed and wrote the screenplays for “Tequila Sunrise,” “Without Limits” (written with Kenny Moore) and “Ask the Dust,” set in Depression-era Los Angeles.

Towne also co-wrote the 1984 film “Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes,” which was based on the Edgar Rice Burroughs novel “Tarzan of the Apes,” a project Towne had been working on for many years. But Towne, who was originally slated to direct, was so unhappy with the finished film, co-written by Michael Austin and directed by Hugh Hudson, that he had his name replaced in the credits with a pseudonym: P.H. Vazak, the name of his Komondor, a Hungarian livestock guard dog, who then went on to share an Oscar nomination with Austin.

Robert Towne, left, directs Colin Farrell as Arturo Bandini in the movie “Ask the Dust” in 2004.

(Paramount Classics)

But none of Towne’s screenplays obtained the enduring stature of “Chinatown,” which continues to be studied by writers and film-school students and is considered one of the finest movie scripts ever written. Based on a vote of its members, the Writers Guild of America ranked “Chinatown” at No. 3 in its 2006 list of the “101 Greatest Screenplays,” behind “Casablanca” and “The Godfather.”

In presenting Towne with an honorary doctorate of fine arts degree at the American Film Institute’s commencement ceremony in 2014, Coppola said, “You have in your script for ‘Chinatown’ provided the de facto blueprint for aspiring screenwriters, a platonic ideal of both structure and style taught as a template around the world.”

In the 2020 book “The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood,” author Sam Wasson revealed that one of Hollywood’s best-known script doctors received uncredited help himself: For more than 40 years, Towne paid Edward Taylor, a longtime close friend, to help him with his scripts, including “Chinatown.”

Taylor, who was Towne’s literature- and theater-loving roommate at Pomona College and later taught sociology and statistics at USC, began secretly working with Towne on his scripts in the mid-1960s and, according to the book, apparently had no problem with remaining anonymous. Towne, Wasson wrote, continued to consult with Taylor in person or by phone until Taylor’s death in 2013.

Towne, who was not interviewed for the book, made a veiled public acknowledgment of his secret collaborator in an introductory essay for a 1983 limited edition of the “Chinatown” screenplay: While writing “the heart” of the script on Catalina Island in the fall of 1972, Towne received periodic visits by his friend Taylor, whom he described as having been his Jiminy Cricket, Mycroft Holmes and Edmund Wilson since their college days.

Born Robert Burton Schwartz in Los Angeles on Nov. 23, 1934, Towne was 2 when his family moved to San Pedro, where his father bought a women’s apparel store called the Towne Smart Shop. It wasn’t long before Lou Schwartz was being called Mr. Towne.

“I think he liked that,” Towne said of his father, who later became a successful real estate developer, in the Writers Guild Foundation interview. “By the time my brother [Roger] was born, he had legally changed his name.” (Roger Towne later co-wrote the screenplay for the 1984 film “The Natural.”)

The family later moved to Rolling Hills on the Palos Verdes Peninsula and then to Brentwood.

At Pomona College in Claremont in the 1950s, Towne studied philosophy. He also took a creative writing class in which one of his short stories, based on a recent stint working on a commercial tuna-fishing boat, “got everybody’s attention,” he recalled.

While in college, Towne considered becoming a journalist. But by the late 1950s, Towne, who served a stint in the Army, was in Hollywood taking an acting class taught by blacklisted actor Jeff Corey, whose students included James Coburn, Sally Kellerman and Richard Chamberlain. Another student was Nicholson, who became Towne’s close friend.

“My training as a writer really came from seven years of improvising in that class, and coming to have a feeling for what was effective dramatically, what was effective in terms of dialogue and just what people could and couldn’t say to be effective,” Towne recalled.

His first professional break came when another student in the class, Corman, who as a quickie film producer and director was there to learn more about the creative process of actors, offered him a chance to write. “It was tough making a living writing for Roger,” Towne said, “but at least he gave me a start.”

Towne’s first screenwriting credit was for Corman’s “Last Woman on Earth,” a 1960 science-fiction film in which Towne played one of the three starring roles under the name Edward Wain. Under the same name, he also was one of the stars of Corman’s “Creature from the Haunted Sea” (1961). For Corman, he also wrote the screen adaptation of the Edgar Allan Poe short story “The Tomb of Ligeia” (1964), starring Vincent Price.

In addition to his movie work, Towne wrote for television in the 1960s, including “The Man from U.N.C.L.E,” “The Outer Limits,” “The Lloyd Bridges Show” and “The Richard Boone Show.” Much later in life, he was a consulting producer on the popular television drama “Mad Men.”

Towne’s screenwriting career began its upswing when Beatty, the star and producer of “Bonnie and Clyde,” and the film’s director, Arthur Penn, needed help with a script written by David Newman and Robert Benton. For his contributions, Towne was listed in the acclaimed hit film’s credits as “creative consultant.”

As a screenwriter, Towne is described by Peter Biskind in his bestselling book on the New Hollywood era, “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls,” as being “unusually literate” in “a town full of dropouts, where few read books.”

“He had a real feel for the fine points of plot, the nuances of dialogue, had the ability to explain and contextualize film in the body of Western drama and literature,” wrote Biskind.

“He had this ability, in every page he wrote and rewrote, to leave a sense of moisture on the page, as if he just breathed on it in some way,” producer Gerald Ayres told Biskind. “There was always something that jostled your sensibilities, that made the reading of the page not just a perception of plot, but the feeling that something accidental and true to the life of a human being had happened there.”

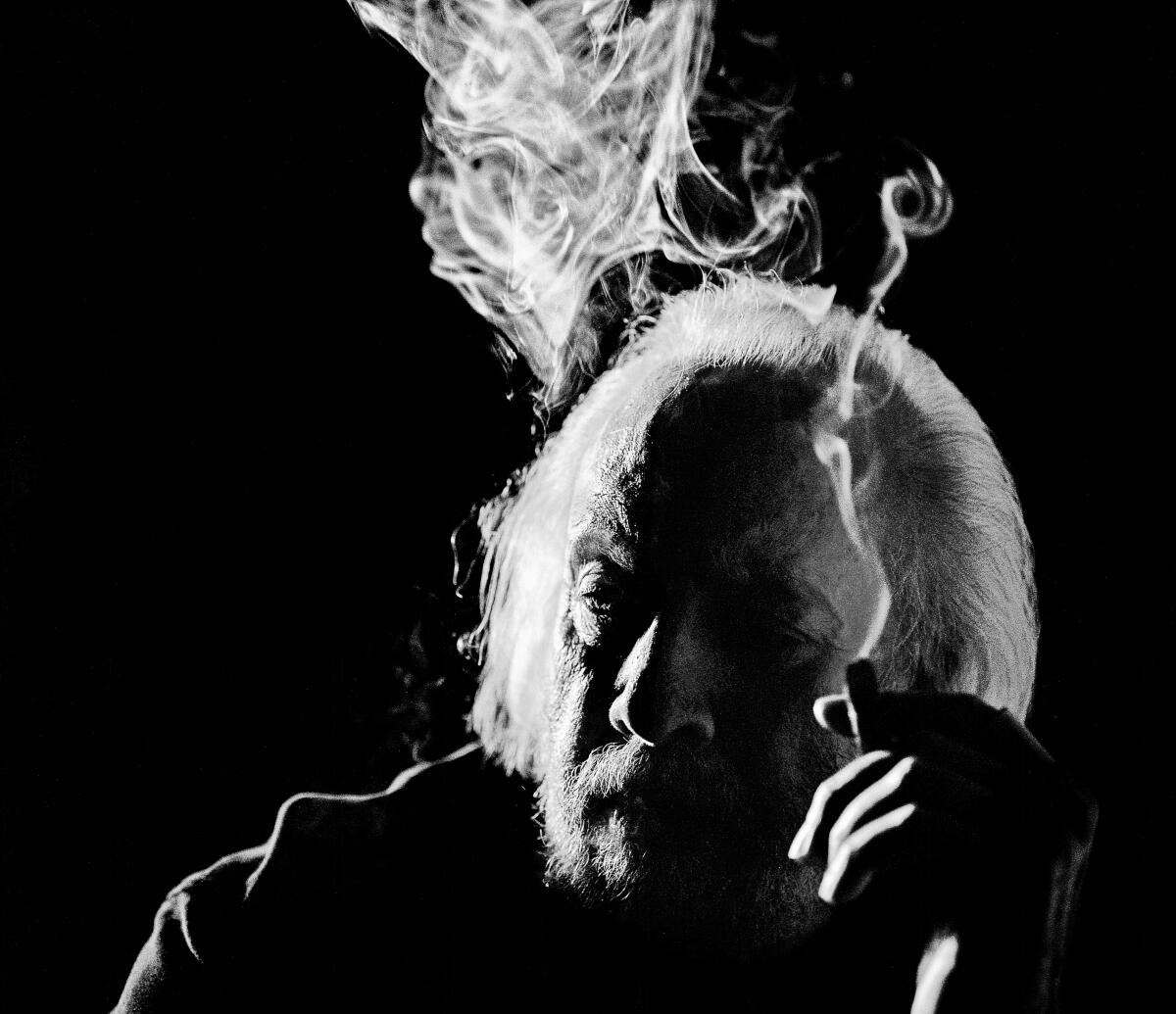

Portrait of Robert Towne in 2006.

(Damon Winter / Los Angeles Times)

In writing “Chinatown,” with its plot revolving around a high-level water and real estate conspiracy, Towne was inspired by elements of the controversial history of the Los Angeles Aqueduct that brought water from the Owens Valley in the eastern Sierra Nevada down to L.A. earlier in the century.

“Everything about it [‘Chinatown’] was an attempt to take an existing genre and imbue it with things from life,” Towne told The Times in 2004. “Not to do an exotic movie about Maltese falcons and jewel-encrusted birds, but to take a crime that was right in front of your face, that was as basic as water and power. And a detective who was not a tarnished knight like Philip Marlowe, but kind of a sleazy, charming, dapper guy who would only take [divorce] cases because they made him the most money.”

Before the filming of “Chinatown” began in 1973, Towne and Polanski argued constantly during the many weeks they spent condensing and revising Towne’s lengthy screenplay.

Their biggest battle was over the ending.

Towne wanted Evelyn Mulwray (Dunaway), the widow of the murdered chief engineer of the Department of Water and Power, to kill her father, the rich and ruthlessly powerful Noah Cross (John Huston), who had raped her as a teenager and was the father of her young daughter, whom she was determined to keep away from him.

But Polanski, whose pregnant actress-wife Sharon Tate had been murdered by members of the Manson family in 1969, had something far more chilling in mind: He wanted Evelyn to die at the end and her daughter fall into the hands of her father — evil triumphant.

The director had his way, and the film comes to its memorably shocking conclusion as Evelyn attempts to flee with her daughter in a car on a street in Chinatown.

A critically acclaimed box-office hit, “Chinatown” received 11 Academy Award nominations, including best picture, director, actor and actress.

And as Towne, the film’s only Oscar winner, told The Times in 1999, he had since come to agree that Polanski “was right about the end.”

In 1997, Towne received the Screen Laurel Award, the Writers Guild of America’s highest award for screenwriting, which is given in recognition of a writer’s body of work.

Towne had a daughter, Katharine, with his first wife, Julie Payne (the daughter of actors John Payne and Anne Shirley); the marriage ended in divorce. He also had a daughter, Chiara, with his second wife, Luisa Gaule.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.