WASHINGTON — Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., is facing a threat a few of his Republican predecessors can relate to: members of his own party vowing to oust him from power.

While Johnson’s predecessor, Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., became the first speaker ever voted out of office last October and John Boehner, R-Ohio, bowed out amid threats of a potential ousting in 2015, it was a Republican speaker more than 100 years ago who first faced an intraparty revolt against his leadership.

Joseph Cannon, known as “Uncle Joe,” ruled the House from 1903 to 1911 and is now the namesake of one of the Capitol’s office buildings. During his term, the Republican from Illinois clashed with the growing progressive movement within his party; a tension that boiled over into a floor fight over the future of the speaker’s role.

With Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., saying she will force a vote next week on deposing Johnson, here is a look back at how Cannon took on his own Republican rebels in 1910 by calling for a vote to oust himself.

‘Czar’ Cannon’s total control

While the U.S. Constitution specifically names the job of House speaker, it only states that the House “shall chuse their Speaker.” That’s it. As a result, the job’s responsibilities have developed and morphed over time depending on who has wielded the gavel.

By the time Cannon came to power, the speakership had been transformed from that of a presiding officer to a powerful party leader. The speaker named all of the committee chairmen and chaired the Rules Committee himself, which directs the flow of legislation to the House floor.

Cannon’s control was so notoriously ironclad that he was referred to as “Czar” Cannon. In his 1964 book “Mr. Speaker: Four men who shaped the United States House of Representatives,” biographer Booth Mooney tells of a constituent who asked his representative for a copy of the House rules, only to receive a photograph of Cannon in return.

While Cannon was largely popular among his peers, he clashed with Republican progressives. These members “introduced foolish or unconstitutional bills, not with the slightest hope that they would become laws but simply to cater to a demagogic or ignorant element” and blame him, Cannon said, according to “Uncle Joe Cannon: The Story of a Pioneer American,” which was written by his secretary, L. White Busbey. This friction came to a head in March 1910.

The revolt of 1910

It all started with a bill about the census. On St. Patrick’s Day in 1910, Rep. Edgar Crumpacker, R-Ind., took to the House floor to say he had a “resolution of privilege” related to the census. Matters considered privileged have precedence over other legislative business on the floor. But the debate over the census resolution was soon overshadowed when Rep. George Norris, R-Neb., one of the leading progressive Republicans, rose to speak.

“Mr. Speaker, I present a resolution made privileged by the Constitution,” the Nebraskan said.

When directed by Cannon to present it, Norris read his proposal to reorganize the Rules Committee by expanding its membership and booting the speaker off of it. That would be a major blow to Cannon’s power.

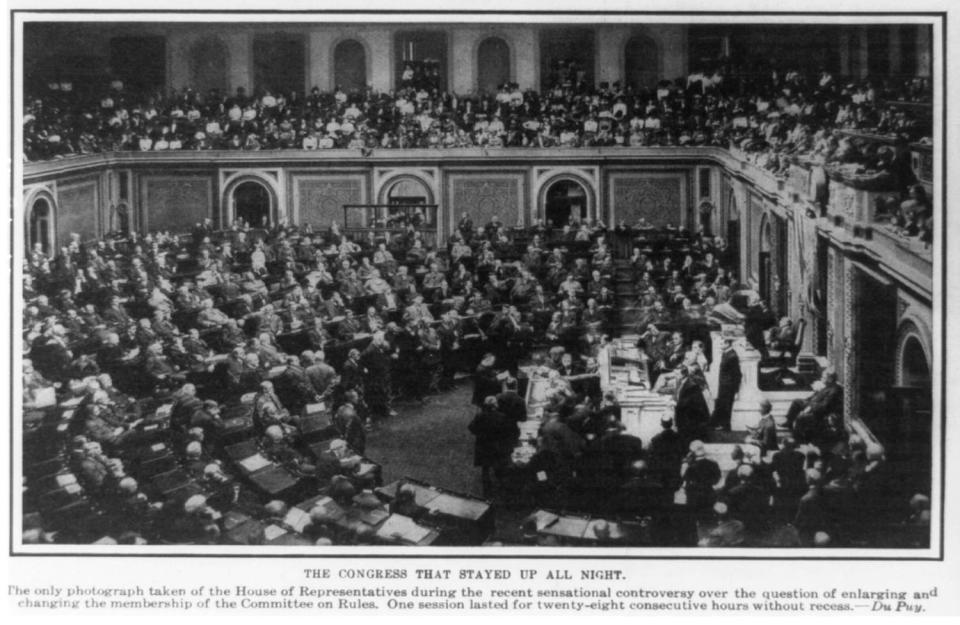

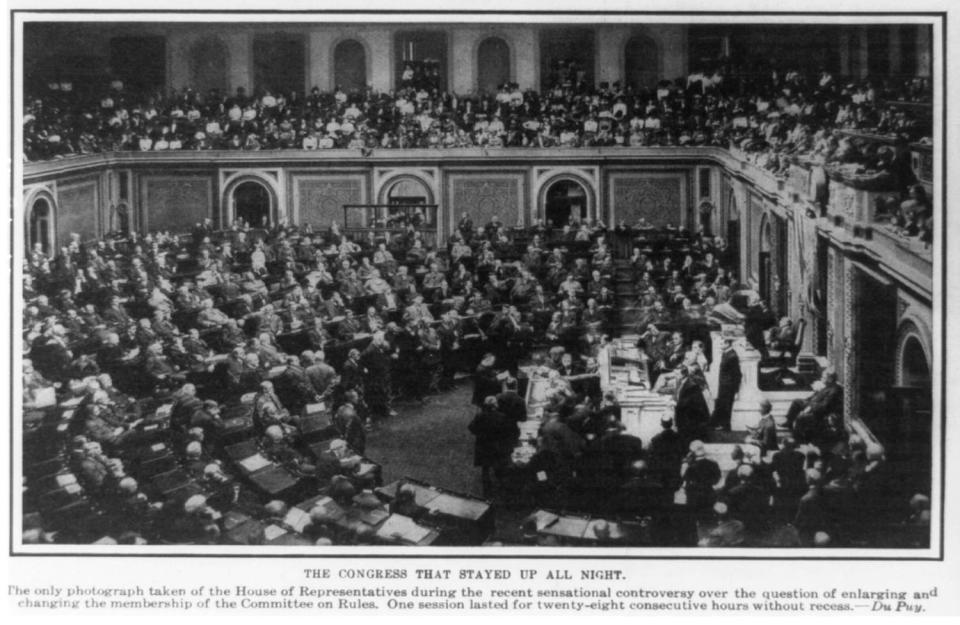

Rep. John Dalzell, a Pennsylvania Republican, immediately cut in to say the resolution from Norris was not privileged. Cannon chose not to rule immediately on that question, so days of intense debate ensued. The galleries in the chamber crowded with spectators and reporters filled every seat available for them, according to newspaper accounts.

“Speaker Cannon is fighting the battle of his life,” observed The Washington Times on the evening of March 18 as floor debate continued. “If he loses this, he is down and out.”

For those unable to see the proceedings in person, newspapers across the country followed the events closely, with headlines like “The Tottering Tyrant,” “Make War on Uncle Joe,” and “Speaker Cannon Doomed.” Even President William Howard Taft was riveted by the press accounts of the fight, according to United Press wire reports, which said that he “eagerly devoured the details of the anti-Cannon fight.”

Eventually Cannon had to make a decision on whether the resolution from Norris to alter the Rules Committee met the criteria to be “privileged.” On March 19, after two days of intense debate, Cannon said it did not. In a rebuke of his authority, the House voted to overrule him, and after more debate adopted the change to the Rules Committee.

“Cannonism was dead, dead as a doornail,” the speaker recounted in Busbey’s book. But Cannon was not done yet.

Cannon calls his opponent’s bluff

As Norris moved to adjourn, Cannon asked for a moment to speak. The speaker addressed the chamber, saying he had two options: resign or declare a vacancy in the office of the speaker and let this new coalition majority of progressive Republicans and Democrats pick his replacement.

Cannon said resignation was off the table because it would be a “confession of weakness or mistake or an apology for past actions,” when he was “not conscious of having done any political wrong.” The Republican side of the chamber erupted in applause.

Then Cannon put the Republican rebels to the test. He said he welcomed a vote to boot him from office. A Democrat followed through and called for such a vote.

When given the chance to remove Cannon, the progressive insurgents balked. Only nine voted to oust him, so the vote failed 155-192, with eight members voting “present” and 33 not voting.

“His Scepter Taken Away, Cannon Is Left On Throne,” is how The Sunday Star in Washington, D.C., summed it up.

Cannon would later say in Busbey’s book that on that day “the Speakership was taken from me amid the rejoicings of my enemies, and it was then handed back to me.”

While Cannon remained as speaker the rest of the session, control of the chamber flipped to Democrats following the 1910 midterm elections. He chose not to serve as minority leader but stayed in Congress until 1923, when he retired two months before his 87th birthday.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com