It’s Leg Day for Jakob Nowell, who’s fueling up for his workout on a recent afternoon with a late breakfast at a Long Beach diner just down the street from his gym.

The only son of the late Sublime frontman Bradley Nowell, Jakob got into weightlifting a few years ago and adheres zealously to his daily exercise regimen. “Working really, really hard,” he says, is a necessity for someone “not naturally good at anything. Growing up, there were all these boy-genius shows like ‘Jimmy Neutron’ and ‘Dexter’s Lab’ on TV. I was always like, These guys are just geniuses at 6 years old? That’s f— up. I knew I was gonna have to cheat to be good, and the best form of cheating is to practice for hours and hours and hours.” He laughs over a greasy plate of steak and eggs.

“Plus, if you work out a lot, you can eat this and not feel like s—.”

What Nowell, 28, has been practicing lately is the music of Sublime, the beloved ska-punk trio his father led from the backyards of Long Beach to the brink of alt-rock stardom until his tragic death in May 1996, just two months before the release of the band’s first major-label album. Bradley was the same age Jakob is now when he died from an accidental heroin overdose after a show at the Phoenix Theater in Petaluma; within a year and a half, Sublime’s self-titled LP had gone triple platinum thanks to unavoidable radio hits like “What I Got,” “Santeria,” and “Wrong Way.”

Now, after decades in which the group’s music only continued to find new fans, Jakob has joined his dad’s former bandmates, drummer Bud Gaugh and bassist Eric Wilson, to front a new version of Sublime. The trio is set to perform in public for just the second time at the upcoming Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, which will also feature a reunion by Sublime’s old pals in No Doubt — perhaps the other defining act of mid-’90s SoCal alternative rock.

“I call Bud and Eric my uncles, and I’m happy they’ve accepted me into their band,” says Jakob, who sings and plays guitar and who was only 11 months old when Bradley Nowell died. “I’ll never look at it as my band. Sublime is my dad’s band, and I’m helping out, that’s all.”

Says Wilson: “This is like a second beginning.”

Formed in 1988, Sublime quickly became a staple of the Long Beach house-party scene with its rowdy yet laid-back blend of reggae, hip-hop, punk and ska. Bradley’s witty and empathetic songwriting distinguished the band, as did his flexibility as a vocalist: In an era of one-note barkers, here was a guy who could croon, growl, toast and rap; he could even sing convincingly in Spanish, a reflection of the deep cultural diversity of the town that also gave us War, Snoop Dogg and Jenni Rivera.

“I used to love to go see them because — and I mean this really affectionately — two out of three gigs, they’d be a total mess,” says No Doubt’s Tom Dumont. “But then that one out of three, they were just transcendent.”

In 1995, L.A.’s influential KROQ-FM started spinning Sublime’s “Date Rape,” a sneering ska tune about sexual abuse. The song’s buzz led to a deal with MCA Records for what would be the band’s third LP; Sublime had completed the album and was on the road awaiting its release when Bradley was found dead in a San Francisco hotel room.

Having declared that there was no Sublime without their talented frontman, Gaugh and Wilson went on to form the Long Beach Dub Allstars; Gaugh also played in a short-lived supergroup, Eyes Adrift, with Krist Novoselic of Nirvana and the Meat Puppets’ Curt Kirkwood. Yet Sublime’s music — its catchy, relatable songs about “the dramedy of life,” as Gaugh puts it — endured, spawning cover bands and collecting praise from high-profile fans such as Vampire Weekend’s Ezra Koenig, who’s called Sublime one of his group’s patron saints, and Lana Del Rey, who recorded a take on Sublime’s “Doin’ Time” in 2019. (With a laugh, Gaugh recalls the time a friend told him about overhearing someone’s reaction to Sublime’s original in a Santa Monica bar: “They were like, ‘Oh my God, that’s the worst f—ing Lana Del Rey cover I’ve ever heard.’”)

On Spotify, “Santeria” has more than 700 million streams while “What I Got” is approaching the half-billion mark — figures all the more impressive given that both songs still seem to turn up on the radio every hour or so. “And that’s not just in Southern California,” says Lisa Worden, who oversees rock and alternative programming for the national iHeartMedia conglomerate. “All my stations play Sublime.”

Bradley Nowell, with guitar, fronts Sublime onstage in 1995.

(Steve Eichner / Getty Images)

Part of what kept the band’s music in circulation — “Sublime” is currently certified for sales of more than 5 million copies — was Sublime with Rome, a sort of living tribute that Gaugh and Wilson assembled in 2009 to perform Sublime’s songs onstage with the singer and guitarist Rome Ramirez. But everyone close to the original Sublime says that Jakob’s presence puts the new project in a different league.

“It’s so surreal,” says Troy Nowell, Bradley’s widow and Jakob’s mom. “But this really is Sublime.” Adds Joe Escalante, the longtime member of Orange County’s Vandals who’s serving as one of Sublime’s managers: “It’s like Walt Disney getting unfrozen.”

Jakob first got together with Gaugh and Wilson late last year to play a benefit for H.R., frontman of the pioneering hardcore band Bad Brains, at L.A.’s Teragram Ballroom.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Jakob first got together with Gaugh and Wilson late last year to play a benefit for H.R., frontman of the pioneering hardcore band Bad Brains, at L.A.’s Teragram Ballroom. The collaboration had been a long time coming — Jakob says people have been floating the idea for his entire adult life. But he’d always been reluctant for personal and musical reasons.

The younger Nowell grew up between San Diego, where he lived in “kind of crazy white-trash” circumstances with his mother and stepfather, and Long Beach, where he spent the summers with his paternal grandparents, “who were much more stable,” he says between bites at the diner. As he’s eating, a server comes by to say hello and offers a memory of Jakob as a baby in a car seat plopped on the table. The mythology that had grown up around Bradley after his death — not to mention Jakob’s own drug problem that began when he was 12 — interfered with his ability to connect with a man he’d never really known; today Jakob says he’ll never return to his father’s grave in nearby Westminster “because it’s hard to mourn when there’s a bunch of strangers around you.”

His taste was also different: As a teen, Jakob loved Tool and Queens of the Stone Age and eventually started a hard-rock band called Law. He cringes at the thought of looking up an old video of him trying to sing Sublime’s “Caress Me Down” at someone else’s behest. “Folks assume I’ve just always known all of Sublime’s songs,” he says. “But they weren’t, like, downloaded into my DNA. This is not something I ever thought I’d do.”

His thinking began to change last year while he was on tour with his solo act, Jakobs Castle. In Petaluma he made what he calls a “spiritual pilgrimage” to the Phoenix Theater, where Bradley played his final gig, and happened upon a recovery meeting in a room with Sublime stickers on the walls; for Jakob, who’s been sober for seven years, the coincidence felt like some kind of sign.

Says Troy Nowell: “I don’t know if Bradley’s somewhere in the other dimension turning knobs, but Jake just stepped up.”

“Folks assume I’ve just always known all of Sublime’s songs,” Nowell says. “But they weren’t, like, downloaded into my DNA. This is not something I ever thought I’d do.”

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Both Gaugh and Wilson say Jakob is the only person for whom they’d consider reviving Sublime, which beyond Coachella is booked for a handful of other festivals including June’s No Values in Pomona. Gaugh stopped playing with Sublime with Rome back in 2011, while Wilson announced in February that he’d quit the band, which has worked steadily over the last 15 years. “It had started to feel like a factory,” the bassist says. “They were using backing tapes and click tracks. It was like a well-greased machine, and that’s not Sublime.”

Despite Wilson’s departure, Sublime with Rome has a tour booked through the fall, which clearly vexes the members of Sublime. Gaugh notes the potential for confusion among fans, saying a friend reached out excitedly the other day to tell him she’d bought tickets for their show in Maui — a Sublime with Rome date, as it turns out.

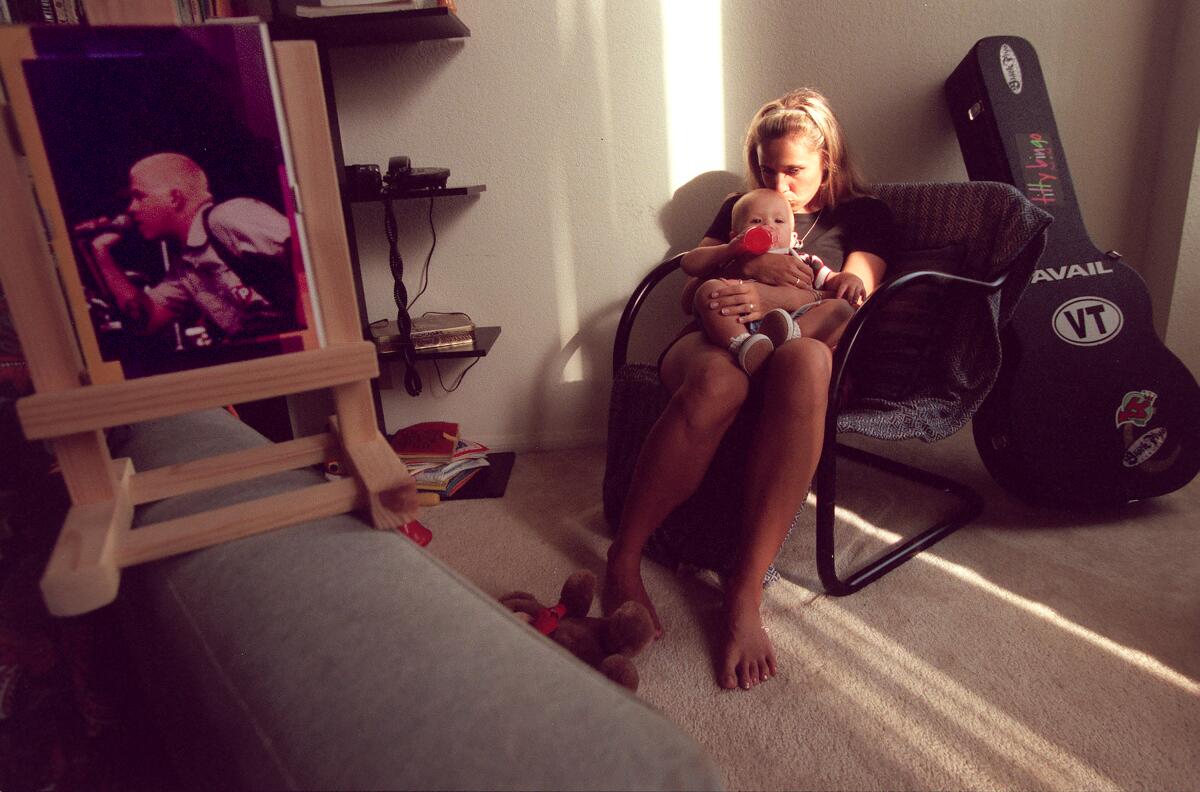

Troy Nowell holds her 1-year-old son, Jakob, in 1996.

(Clarence Williams / Los Angeles Times)

Jakob views Rome’s decision to keep going in more dramatic moral terms. “That guy literally thinks he’s entitled to play as a band with no members of the original band in it,” he says. “Everyone’s like, ‘Well, he really kept the dream alive.’ Kept the dream alive? There are kids wearing Sublime shirts right now that don’t say ‘with Rome’ on them. What are we talking about here? It’s insanity. The truth is that he thinks he can continually profit off of a family’s tragedy without any connection to it.”

“It breaks my heart if he thinks that’s true,” Ramirez says. “Not in the least do I feel any sort of sense of entitlement to play as Sublime. In my eyes, Sublime has and will always be Brad, Bud and Eric.” Ramirez adds that he’d prefer to play his band’s upcoming dates — most of which he says were booked more than a year ago, well before Wilson left — under the name Rome. “I don’t want to be up there playing billed as Sublime because it’s not,” he says. “But unfortunately, legally, we are obligated to play these shows.”

“I call Bud and Eric my uncles, and I’m happy they’ve accepted me into their band,” says Jakob, who sings and plays guitar and who was only 11 months old when Bradley Nowell died.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Jakob says he called Ramirez before Sublime announced it was playing Coachella to discuss “how we were gonna handle this media rollout.” Yet Ramirez, he adds, only wanted to know how many shows the band planned to play. “How many shows am I playing with my dad’s band?” Jakob recalls. “You’re tripping, bro.”

“We talked for like 40 minutes,” Ramirez says. “There was never any mention of them wanting to work amicably on the launch of this tour.”

Jakob sighs. “He’s just shown me and my family no kindness. And if anything me and Rome should be best f— friends,” he says. “I mean, who else could better relate to living in another man’s shadow for the entirety of your career?”

That’s how Sublime feels to Jakob? “It’s always felt like a lot has been hinging on me,” he says heavily. “But you either get busy riding or you get busy dying. I’m a strong person, and although I have my low moments, I’ve picked myself up from them.

“If I wasn’t the right person for the job, I wouldn’t be doing it.”