When the Nord Stream gas pipeline between Russia and Germany was damaged by mysterious explosions in 2022, the resulting leaks of methane were so big they could be seen from space. And, for one company, they were especially notable: they helped to prove its technology for detecting emissions by satellite.

GHGSat, which operates the largest collection of greenhouse gas-monitoring satellites, had already been developing the ability to detect offshore leaks of methane, as the gas has much more warming power when in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide.

“We had done a bunch of R&D to convince ourselves it worked, but Nord Stream was so big it was the first really clear example to demonstrate what we could do,” says Stephane Germain, founder and president of the Montreal-based company. “Since then, we’ve commercialised that offshore service. It’s something many companies are buying from us now.”

A former Bain consultant and aerospace executive, Germain set up GHGSat in 2011 after Quebec and California announced they would combine their emissions-trading networks to create the largest such market in North America. “It just made me realise that, when you put a price on a tonne of carbon, that’ll create a financial risk for the operators that have emissions,” says Germain.

“They should be motivated to understand what their real emissions are, what the measured emissions are, instead of just the estimated emissions, which have notorious uncertainties and inaccuracies.”

GHGSat has focused on methane, which leaks when coal, gas or oil is extracted and transported. Other sources include farms and waste dumps. It is estimated to be responsible for 30 per cent of the rise in global temperatures since the Industrial Revolution, so cutting these emissions is a relatively easy way to combat climate change. But, until recently, there was no clear picture of where the methane was coming from.

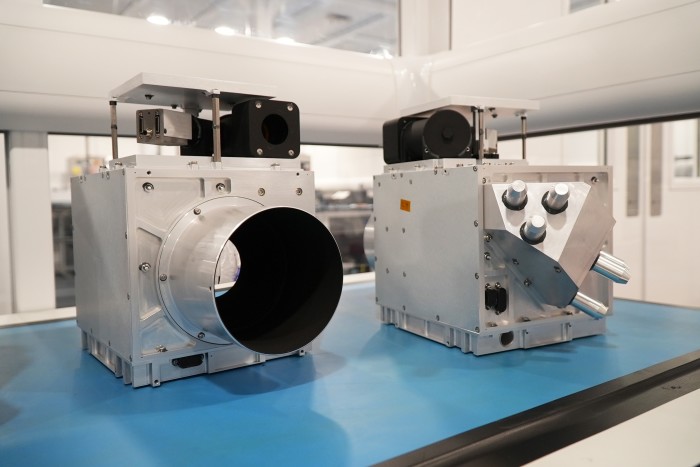

GHGSat’s satellites can provide one using infrared sensors. They detect the signature of methane in the atmosphere by observing the way the gas absorbs sunlight reflected off the Earth’s surface. Last year, GHGSat detected methane equivalent to 0.5bn tonnes of CO₂, double the level it achieved in the previous year.

Globally, methane levels stayed close to a record high last year, according to the International Energy Agency, despite pledges at the UN COP26 summit in 2021 to cut them by 30 per cent between 2020 and 2030.

GHGSat has 12 satellites in orbit and plans to launch four more this year, each monitoring emissions for clients in the oil and gas, waste management, and mining industries, as well as governments. It sits at number 21 on the FT-Statista list of the 500 fastest-growing companies in the Americas. Revenues at the company rose from a few hundred thousand dollars in 2019 to $20mn last year, and it now has nearly 150 staff. In 2023, it also added a satellite capable of detecting CO₂, which is harder to track as there is more of it in the atmosphere.

Methane leaks have been increasing: the number detected by satellites rose 50 per cent in 2023, year on year, according to the IEA. Some 5mn tonnes of leaks were detected from fossil fuel facilities, including a well blowout in Kazakhstan that lasted for more than 200 days.

Germain says a change of attitude is needed in the industry. “It’s been a real eye-opener to realise how much of the problem in oil and gas could be readily addressed by different maintenance or operating practices,” he says. “It starts with best practices shared between companies. It absolutely is accelerated by government — regulations, enforcement, taxes, different mechanisms.”

Emmanuel Corral, senior analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights, says climate worries have “spurred investments in this technology from governments, research institutions and the private sector”. Further boosts have been provided by improved sensors, smaller and cheaper satellites, and the use of artificial intelligence to analyse the data gathered.

GHGSat is currently involved in a methane-detection programme aimed at emerging markets, through the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, which comprises 12 energy majors. GHGSat also shares data with Nasa and the European Space Agency.

One collaborative project started when GHGSat was monitoring natural eruptions of methane from a mud formation in Turkmenistan. It noticed further emissions nearby, which turned out to be an oil and gas facility. The company contacted SRON, the Dutch space research institute, which verified the findings using an ESA satellite. GHGSat alerted the authorities in Turkmenistan and, six months later, the emissions stopped.

“With that kind of collaboration, you have really powerful complementarity between all these different systems and technologies, to ultimately give actionable information to operators,” Germain says. “For us, collaboration is critical. We go at it differently, but we all see the value in bringing these different sensors to bear together to get to that common goal.”

Such data could be used to publicly expose repeat offenders, but Germain prefers a collaborative approach. “We fundamentally believe we will get more impact, greater mitigation of methane, by working as a partner with industrial operators and with governments than by publicly naming and shaming,” he says.