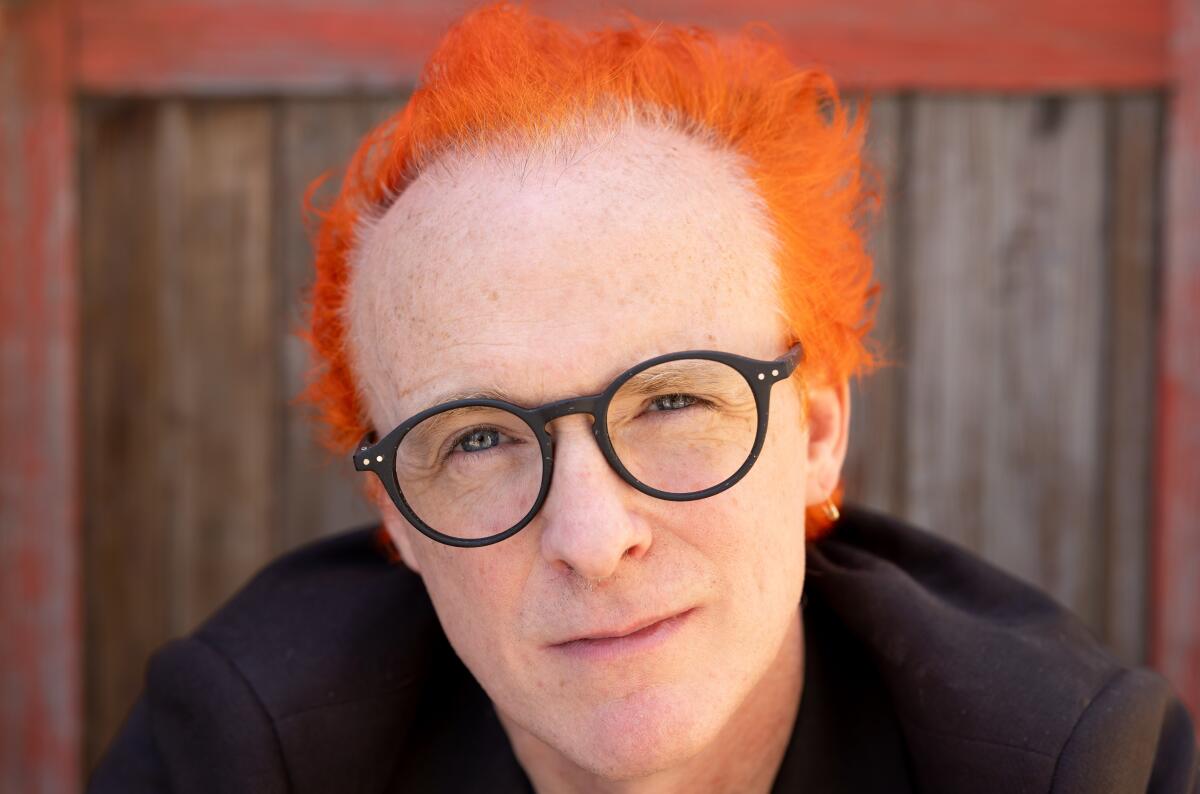

At 50, Fran Healy, frontman/rhythm guitarist of the band Travis still looks every bit the rock star, even when he doesn’t feel like one.

His neon-orange dyed hair, hoop earring, wiry frame and monochromatic black outfit contrast with his deferential demeanor as he humbly rejects the rock star label. “I really don’t see myself that way,” he says in his thick Scottish accent while sipping tea in the kitchen of his 115-year-old L.A. Craftsman house in Venice. “I think narcissists generally see themselves like that. They are drawn to our business because of the nature of it, but I’m writing because I want to express myself. It’s therapeutic.”

The introverted Healy prefers his songwriting to lead while he remains closer to the shadows. His unassuming nature is reflected on the cover of Travis’ new album “L.A. Times,” its 10th full-length release, produced by Tony Hoffer (Belle and Sebastian/The Kooks), features the downtown Los Angeles skyline illuminated at night and features Healy and his bandmates (lead guitarist Andy Dunlop, bassist Dougie Payne and drummer Neil Primrose) standing on a dimly lit street in Victor Heights.

However, Healy notes, he “can switch ‘it’ on” for live performances. His striking hair color, he explains, follows cogent advice he received long ago. “Someone once told me, ‘Look the part, become the part,’” he recalls. “We’re putting out a new record, and it’s an important record for us, so I wanted a hair color that would be eye-catching onstage.”

Until recently, Healy wore a mustache and beard and kept his predominantly gray hair in a ponytail. After years of experimentation, he stopped fussing with his hair once his son Clay was born in 2006. It prompted a shift in his priorities. Instead, Healy fully devoted himself to fatherhood and being “the dad I never had,” he says.

Born in Stafford, England, Healy was raised by his mother in Glasgow, Scotland, after his parents split up. Healy’s mentally ill father was mostly absent from his life.

Healy humbly rejects the rock star label. “I really don’t see myself that way,” he says in his thick Scottish accent. “I think narcissists generally see themselves like that.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Yet what served Healy’s relationship with his son inadvertently impacted his relationship with songwriting, which, he admits, was not his best on several Travis records after his son’s birth. “I was completely dialing it in, and it shows in the quality of the work,” he says, while noting that it’s a conclusion he arrived at in hindsight.

However, once Clay—who turned 18 earlier this year— entered his later teens, Healy felt comfortable to loosen the reins of fatherhood which gave him sufficient time to dedicate to music, yielding the 10 songs on “L.A. Times.”

With infectious melodies and unbridled humanity, “L.A. Times” recalls the potent songwriting that made Travis superstars in the U.K. in the late ‘90s.

The album’s title, “L.A. Times,” blends Healy’s past in Glasgow, where a newspaper seller stood outside to hawk the evening edition while repeatedly shouting “Final Times,” with his current life in Los Angeles, where he moved in 2017 with his then-wife Nora Kryst. The couple split several years later after 23 years together.

Their parting and the death of Healy’s close friend Ringan Ledwidge (to whom “L.A. Times” is dedicated) left Healy with much to ponder on the new record. Remarkably, he predominantly celebrates life in his songs instead of succumbing to cynicism, regret or fear.

On the intimate “Live It All Again,” Healy grieves his former marriage with heartfelt vocals accompanied by an acoustic guitar. Amid confusion and strife, he honors Kryst and their relationship, which birthed their only child, singing, “In spite of all the pain, if I could turn the clock back I would live it all again.”

Acknowledging the fleeting nature of life, on the anthemic “Alive,” written after the loss of Ledwidge to cancer, Healy reminds himself not to take his health for granted or dwell on life’s minutiae. “What’s the use in worrying before the course is set? … Please don’t forget we are alive,” Healy sings with his characteristically earnest and emotive vocals.

Continuing in the vein of not wasting time in life, Healy commemorates extricating himself from a toxic situation on the plucky “Gaslight,” and on the mellow, mid-tempo “Raze the Bar” Healy beautifully memorializes the now-shuttered New York City bar Black and White, along with its owners. “So here’s to a new day. To hell with the past,” Healy sings, offering a farewell toast to the establishment in the song’s uplifting bridge. “Here’s to the future as long as it lasts. Raise a glass.”

The album’s title, “L.A. Times,” blends Healy’s past in Glasgow, where a newspaper seller stood outside to hawk the evening edition while repeatedly shouting “Final Times,” with his current life in Los Angeles.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

The bar’s camaraderie resonates further due to backing vocals contributed by two of Healy’s famous longtime friends, The Killers’ Brandon Flowers and Coldplay’s Chris Martin. The latter has famously called himself a “poor man’s Fran Healy” and has credited Travis as “the band that invented my band and others.”

Formed in Glasgow in 1991 and named after drifter Travis Henderson (portrayed by actor Harry Dean Stanton) in Wim Wenders’ 1984 film “Paris, Texas,” Travis released the moderately successful rock-infused debut studio album, “Good Feeling,” produced by Steve Lillywhite (U2, Dave Matthews Band), in 1997.

But the melancholic and sweeping “The Man Who” two years later, was Travis’ commercial breakthrough record. The chart-topping, Brit Award-winning album, produced by Nigel Godrich (Radiohead, Beck), spawned four hit singles: “Why Does It Always Rain on Me?,” “Driftwood,” “Turn,” and “Writing to Reach You.”

Healy reflects on the late ‘90s, when an unexpected rainstorm 25 years ago at the Glastonbury Festival — or, as Healy puts it, “the freak weather event that changed everything” — catapulted the band to stardom.

In 1999, the then-midlevel band’s future looked as bright as the sun that shone upon them as they took the stage at the famed music event in England. But halfway through the set, as Healy crooned “Where did the blue sky go / why is it raining so?” from the band’s song “Why Does It Always Rain On Me?” the lyrics proved to be disarmingly literal. Suddenly, the skies darkened and it started to pour.

Healy recalls seeing disappointment on the crowd’s faces as the weather turned. What’s more, he and his bandmates felt deflated after the performance. “We thought we played the worst show of our lives,” he says. “We were driving back to Glasgow feeling like our career was over.”

However, to Healy’s surprise, Travis’ Glastonbury appearance was highlighted on BBC Television. “I heard my name on television and it was the weirdest and most surreal thing that could ever happen,” he says. “And there was [BBC broadcasters] Jo Whiley and John Peel hailing us as the band of the festival.”

In America, Travis’s journey has been less dramatic. The band’s success in the U.K. has never been matched on this side of the pond. Yet Los Angeles has been another story.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

With the added media exposure, “Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” became Travis’ first top 10 hit. Healy notes the irony of the song’s success as he relays his then-manager’s failed attempt to dissuade the band from releasing the song as a single. “‘Nobody wants to hear a song about the bloody weather,’” he said.

While Healy was thrilled about Travis’ rapidly expanding fan base — “The Man Who” spent nine weeks at No. 1 on the U.K. Albums Chart — he was disoriented by the meteoric leap to stardom: “I felt like sometimes we were like a single-propeller aircraft flying at 60,000 feet, and bits were flying off.”

By 2001, fame had taken its toll. While Healy was visiting his mother, she expressed concern about his mental state. The line between Healy’s professional and personal life had become so blurred that he unwittingly had been speaking to her as if a journalist were interviewing him. He broke down and started sobbing when he realized that he had been overthinking every word that came out of his mouth as if he were talking to the press.

He says his watershed moment was partly a consequence of doing endless media interviews. It was also due to the shock of going from anonymity, walking down the street completely unnoticed, to massive stardom, with everyone staring and whispering as they passed by.

As unsettling as it was at the time, Healy is grateful for his “moment of reckoning.” It motivated him to seek professional help. A dozen hypnotherapy sessions led to his recovery and inspired Travis’ 2003 album “12 Memories.”

In America, Travis’ journey has been less dramatic. The band’s success in the U.K. has never been matched on this side of the pond. Yet Los Angeles has been another story. “Something about L.A. connected,” Healy says. “We were this weird little band from Scotland that L.A. fell in love with. There was this love affair that we had and we still have with L.A.”

Healy beams as he recalls Travis’ jampacked, star-studded debut concert in Los Angeles in 2000 at the legendary Troubadour, and looks incredulous as he reminisces about headlining the Universal Amphitheater the following year.

But performing in Los Angeles is one thing and making it one’s home is another. After Glasgow, Healy, who has lived in New York, London and Berlin, says he appreciates the warm weather and proximity to the ocean, and also the art galleries and restaurants, but multiple bedeviling experiences in the City of Angels have rattled him.

Fran Healy is photographed on a hill overlooking in Los Angeles.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

He relays a terrifying anecdote about nearly being carjacked and also describes being the target of a scary road-rage episode. Then there was the time he came home from a trip and found a man living inside his house. He had broken into it while Healy was out of town.

As he recounts a devastating incident that he experienced, Healy’s emotions are palpable. He shares that he witnessed a man get struck by a car. As Healy waited with and consoled him until paramedics arrived, the victim, who was Black and unhoused, expressed his fear that he might be discriminated against at the hospital. Sadly, Healy learned that the man later died.

A photo of the man that is saved to Healy’s phone is a haunting reminder.

The juxtaposition between haves and have-nots was starkly illustrated to Healy one afternoon near his studio on the edge of Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles, where he spotted a bright yellow Lamborghini driving past an encampment of unhoused individuals. The driver was wearing expensive aviator sunglasses, and his forearm, hanging outside the window, was adorned with heavy jewelry.

The impactful scene sparked the album’s title track, “L.A. Times.” The song, which closes the record, opens scenically with just the sounds of rotating LAPD helicopter rotor blades and a siren followed by music and then Healy’s voice: “I look around and all I see is pain and suffering reflected on the 50 facets of a diamond ring,” he says.

With vocals composed exclusively of spoken word, except for the occasional melodic “la-la” sung in the background, the unique composition departs from Healy’s typically tuneful style, and has more in common with hip-hop. It was after he struggled to find a melody that Healy instead found himself unleashing a cathartic stream of conscious rant about Los Angeles’s socioeconomic ills, climate change, and the ever-looming threat of a catastrophic earthquake along the San Andreas Fault.

“I’d been wanting to let off steam and have a big moan about all of the things I’m surrounded by,” he says. “I got a whole lot of stuff out like I had lanced a boil and sucked the poison out of something.”

Ahead of the release of “L.A. Times,” Healy will soon head overseas to tour in support of the new record. He pauses momentarily, however, lamenting the digital era and says nobody buys records anymore. Yet just as quickly, he regains his cheerful demeanor. “I don’t care,” he says. “I’ve spent the last four years recalibrating and refocusing, and I’ve gone back to my hole where I dig for melodies. I have a record now that I think is one of our best. I’ve done my bit. I’m making songs.”