Ballerinas stir in the early afternoon light that shines through a fountain and into the studio. A jeté flashes in silhouette, a pirouette vanishes like a whisper. The dance is not there yet, but choreographer Lincoln Jones sees glimmers of grace as he counts to the music and imagines what George Balanchine might have done had he added a fourth act to his famous ballet “Jewels.”

It is provocative to aspire to slip into the mind of one of ballet’s great masters, but Jones, director of American Contemporary Ballet, sees it as a progression in his long devotion to Balanchine’s art. Jones, who rides a BMW motorcycle, aims for a degree of risk in his work. He once had his ballerinas — dressed elegantly as if on the set of “Mad Men” — saunter onto the stage and gather around a pie before falling to their knees like resplendent crows and devouring it.

“That came to me in a single instant,” he said at his studio on South Hope Street in downtown Los Angeles. “They’re walking in heels and it’s supposed to look like a runway walk, but it’s extremely slow until this element comes out that clearly shouldn’t be there and suggests something’s going to happen, and then it happens very fast. It’s the buildup.”

No pastries are expected when Jones’ “Sapphires” opens June 6. The piece is his rendering of a dance Balanchine thought about but never realized for “Jewels,” a plotless ballet comprised of three movements that evoke the beauty of precious stones and places significant to the Russian emigré: “Emeralds” for France set to the music of Gabriel Fauré, “Rubies” for America set to Igor Stravinsky, and “Diamonds” for his native imperial Russia with a score by Pyotr Tchaikovsky.

Read more: Review: The archaeology of dance: American Contemporary Ballet digs back to 1890 with revelatory results

“‘Jewels’ was a walk through the musical geography of Balanchine’s life,” Jennifer Homans wrote in her biography “Mr. B.” The ballet was “a gift to his dancers” and the production, with its gem-studded costumes, was intended as “a play of windows and mirrors, real and reflected, appearances and light.”

When the New York City Ballet premiered “Jewels” in 1967, the New York Times praised it as “a wholehearted spectacle not to be missed.”

As he watched his ballerinas rehearse “Sapphires,” Jones, who grew up in Fullerton and once danced for the Metropolitan Opera Ballet in New York, suggested that a dance, especially one Balanchine might have summoned, should flow like the cadence of a sentence or an unbroken contrail. A precise conspiracy of gesture and timing. Then he stopped the music and told one of his dancers, “Don’t race too quickly.”

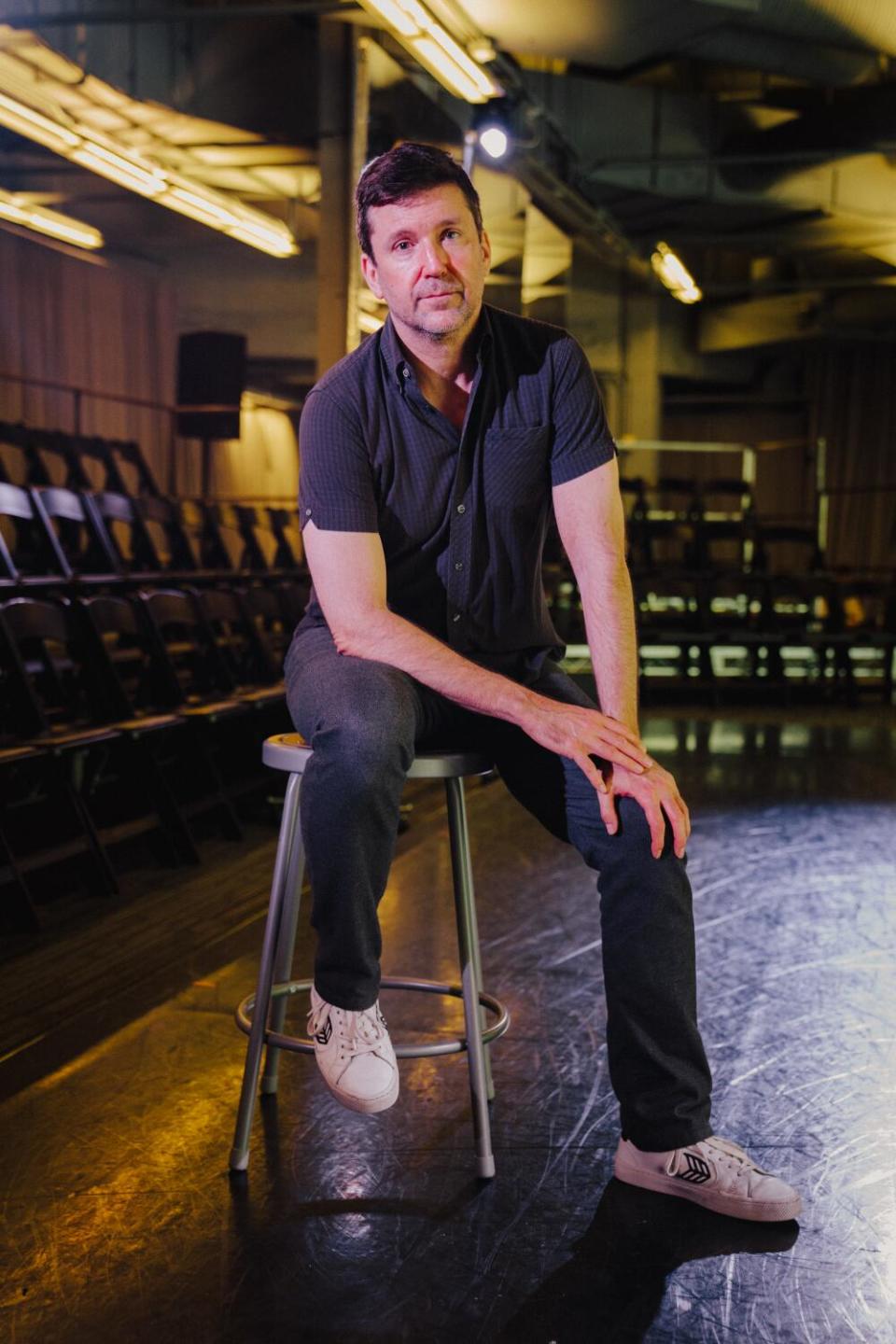

Jones is at once affable and intense — a polite slyness radiates off him. He studies his dancers as if breaking down and reconfiguring elements in works that can be both seductive and playful. He is artist and nomad, choreographer and businessman who, in a perpetual search for studio space and favorable leases, has moved his company 10 times since co-founding it here with Theresa Farrell in 2011. Jones took a break from rehearsal the other day to talk about “Sapphires,” Balanchine and how a trip to Disneyland as a child taught him about aesthetics.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

What was the genesis of “Jewels”? What was Balanchine trying to convey?

The idea was supposedly suggested by Claude Arpels of the jewelry firm Van Cleef & Arpels. I think Balanchine was hoping to get funding from him. The ballet worked perfectly in creating a unified idea to give you three things that were very different and to explore what made them the same. If you see “Jewels” live, as you shift from the colors of green, red and diamonds, it has this huge visual impact. Balanchine was so good at drawing out simple elements that could be abstracted into other things.

The “Sapphires” section was never realized. Balanchine, who died in 1983, had reportedly said that the color was too hard to get across onstage. What was difficult about that?

My guess is because of the darkness of blue. For our intimate venue [Jones’ dancers are often only an arm’s length from the audience] it works. But for a larger stage I can see it not popping as much as the other jewels. That was way more than enough to deter him. Balanchine was a very theatrical thinker, but he did it with such limited means. It’s one of the things that makes his art so great — the efficiency with which he creates such impressive effects.

Is it a bit brash for you to imagine what Balanchine might have done? Like a writer taking on an unfinished Hemingway chapter?

Or stupidity. [Laughs]

Why are you doing it? Is it an imagining of his influence on you?

Choreography is unusual. Of the classical arts, there is little intellectual history in terms of how to do it. If you study music, you can find a million books on theory. But not in ballet. The best way for me to train was to study a master and try to learn everything I could to [understand] his work. Throughout the 20th century, you were supposed to be born as an artist and invent a new language. I very much disagree with that. I think that you have to master what came before and then maybe you’ll have something to say. The idea of taking a specific world of Balanchine’s and trying to make an extension of it is [like] trying to make a sequel to “Star Wars.” What made “Star Wars,” “Star Wars”? It holds your own work under an intense microscope. How much do you know about one of the most impactful ballets and what will that look like?

Read more: ‘Burlesque,’ a new Lincoln Jones ballet, a new collaboration with Charles Wuorinen and why it works

Where do you see Balanchine’s imprint in your work? Where is it the same — and different?

I’m trying to learn from him. Not his vision but his craft. His ballets are effective in ways no one else’s are. Why is that? How is he matching steps to the music? How is he constructing step phrases? If you look at any visual artist’s work, you’ll see they’re attracted to certain lines and line shapes. I’m attracted to a different set of lines than Balanchine is but I don’t want to give up any of the technology that he’s left us. Whenever anybody asks me about Balanchine, I think of what Jack Nicholson said about Stanley Kubrick: “Everyone pretty much acknowledges him as The Man, and I still think that underrates him.” Dancers everywhere love to dance his work. I think he’ll come to be the only choreographer remembered from the 20th century.

Your “Sapphires” is set to the music of Austrian American composer Arnold Schoenberg, who fled the Nazis in the 1930s and emigrated to the U.S. Why did you choose Schoenberg?

Balanchine did plan to choreograph it to Schoenberg. It’s the first piece Schoenberg wrote when he moved to Los Angeles. It’s very unique. Many would call him the master of modern [atonal] music — music that for most people does not sound melodic. But Schoenberg said he often longed to write in the old style. The piece is called “Suite for String Orchestra in G Major.” There’s only two recordings of it that I know of. The music references what the Baroque composers were doing — the precursor to the modern symphony. It would be a collection of dances because at the time that’s what you did, you went out and danced. This is explicitly a throwback to that. I thought it was the right time to do it. It’s the 150th anniversary of Schoenberg’s birth. We’ll have a live 16-piece string orchestra.

You’re paying homage to Balanchine, but he is a revered figure. Any trepidation about putting this show on?

Absolutely. You want it to look like him but not a copy of him. I cannot fully channel what he would have done. When you’re imagining what Balanchine would do, your mind is going to what his ballets were. But then are you pulling too close to his steps? You have to go the other direction a little bit.

The core of your work is ballet, but since you came from New York to Los Angeles more than a decade ago you’ve expanded. You write skits. Your dancers sometimes look like they stepped out of Vogue magazine. In your show “Homecoming,” they were dressed as cheerleaders. In your most recent performance, you created a New Orleans jazz club complete with a live band and a stand-up comic. What are you trying to bring to ballet?

I think it’s more of trying to bring ballet back to its natural state. Ballet has evolved into something that is a bit anachronistic and not ideal for the art. If you go back to the 15th and 16th centuries, ballets were like a party, like combining the Met Gala with a high school prom and a giant party — that’s what it was. That’s why we have dances with the audience after our shows. That participatory element. My goal is to create an experience today that has the depth of [the art of the past] but also the immediacy of what those things had in their own time. Any good performance surprises. I enjoy having elements people aren’t expecting. I like to draw themes out into different mediums, to be immersed in something. When I was a kid going to Disneyland, it was such a huge thing. It was the first time I had ever seen an aesthetically unified world.

Much of your work is cinematic. Why?

I want to use elements from the world that people live in so they can ease into the work, and you’re not immediately presenting a stylistic barrier where they have to get through the barrier to then get into the art. I want it to go straight through. It’s really what I want to see visually.

How difficult is it these days to keep a ballet company running? There’s fundraising, expiring leases and economics balanced against what you want to say artistically.

It used to drive me crazy that I couldn’t spend all my time on art, but I’ve actually learned about art from doing the other stuff. I still do a lot of fundraising myself. [The company’s ballets cost between $90,000 and $250,000, including live musical ensembles, to present.] I oversee the marketing because the company’s creative photos are so incredibly important to me. One of the things that slows us down is that everyone is waiting for answers from me while I’m working on the ballet. Economically, it’s a challenge. Philanthropy has changed over the years. I think a lot of times the goal of art is now seen as education or having a social purpose and a lot of the funding ends up going in that direction. It used to be for funding pure art. My goal is to show people that the funding for the sake of art itself is very valuable.

Get notified when the biggest stories in Hollywood, culture and entertainment go live. Sign up for L.A. Times entertainment alerts.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.