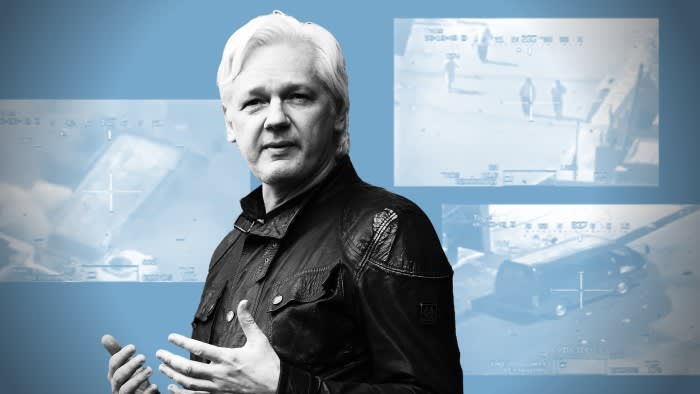

Julian Assange had already been ruffling feathers for several years when, in 2010, the Australian hacker and publisher released leaked footage of a US helicopter crew gunning down unarmed Iraqis on a Baghdad street.

The video, dubbed Collateral Murder, was among thousands of classified US military documents that the WikiLeaks website published at the time. As much as any, it put its founder on a collision course with America that only this week — 14 years later — is reaching some form of resolution.

Assange this week walked free from Belmarsh high-security prison in London, where he has been incarcerated since 2019, fighting extradition to the US on espionage charges.

He was on his way by plane to the US-controlled Northern Mariana Islands in the Pacific where, in return for a sentence of time served, he will plead guilty to one charge of conspiracy to obtain and disseminate classified information. Other charges relating to the publication of the material have been dropped.

Assange will then be free to return to his native Australia, without whose patience and diplomatic support some allies believe he might never have seen this day.

“It’s debatable whether this is a victory for freedom or not,” said Vaughan Smith, founder of the Frontline Club, the group for journalists in Paddington where Assange stayed in the months that he was first polarising global opinion.

At the time, supporters saw him as a fearless warrior for press freedom, exposing double standards at the heart of power. Detractors were forming a different view: they saw a dangerous gadfly, disclosing information regardless of the consequences.

Smith, who has remained a loyal friend, said that whichever way you look at it, Assange has been through a terrible ordeal.

Facing allegations of rape in Sweden, which he denied, he spent seven years holed up in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, attracting support outside the gates from a diverse crew of celebrities including Pamela Anderson, Lady Gaga and the former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis.

Once the Ecuadoreans had tired of him, he was arrested and sent to Belmarsh. “It’s pretty sobering the way he has been made to suffer,” said Smith.

Collateral Murder was published in 2010 alongside a trove of classified US military documents relating to the Iraq and Afghan wars. These were obtained from Chelsea Manning, the former US army intelligence analyst, who served seven years of a 35 year sentence for her part in the saga.

Shot from an Apache helicopter gunship, the footage exposed casual rules of engagement by US troops, along with a loose relationship with the truth on the part of commanders who had portrayed victims of the 2007 incident as armed.

It was one explosive element in a huge data dump that was highly damaging to the reputation of the US military. Two of the 11 civilians killed were employees of the Reuters news agency.

At first the information from WikiLeaks was published in careful collaboration with The Guardian, New York Times, Der Spiegel, El País and Le Monde newspapers, redacted to protect the identities of sources and personnel involved.

But later — after Assange had fallen out with some of the newspapers he had worked with, and a German hacker had accessed the files — WikiLeaks released the raw documents en masse, along with more than 250,000 US diplomatic cables.

Alan Rusbridger, former editor of The Guardian, said the advent of WikiLeaks, which started life in 2006 exposing corruption in Kenya, marked the beginning of a “new era of transparency”.

At the same time, journalists are enduring a sustained backlash as western intelligence agencies come down hard on anyone touching classified information.

“The stuff on Iraq and Afghanistan needed to come out,” Rusbridger said. The diplomatic cables were less impactful, he argued, in part because many of them made for “sensible” reading: “It does make you reconsider why all this stuff has to be so secret.”

For the Americans, some of the less-than-diplomatic language used in the cables damaged relations with allies.

Worse, they claimed, it brought sources who were exposed into harm’s way.

At the time of Assange’s indictment in 2019, John Demers, the then-top justice department national security official, said: “No responsible actor, journalist or otherwise, would purposely publish the names of individuals he or she knew to be confidential human sources in war zones, exposing them to the gravest of dangers.”

Assange first honed his skills as a teenage hacker in Australia where he also had his first brush with the law. Smith said some of Assange’s later problems were the result of being “different”.

His character, as well as his work, has divided opinion.

“He doesn’t necessarily fit in. From time to time, people who are different have something to say, and humans are inclined to turn on them,” Smith said. The rape allegations, which have passed the point at which they can be prosecuted under Swedish law, had “diminished him and poisoned him in the public eye”, he added.

Others who met Assange along the way were less generous. One described him as “a mercurial guy — sometimes he would behave like a CEO, strategic and efficient. Other times he would be like a badly behaved child.”

UK district judge Michael Snow, who convicted Assange in 2019 for jumping bail in 2012, described him as “a narcissist who cannot get beyond his own selfish interests”.

Even in confinement, Assange remained a potent force, playing a tumultuous role in the 2016 US elections when WikiLeaks released a tranche of emails from the Democratic party. Federal prosecutors said these were originally stolen by Russian intelligence operatives.

Donald Trump, at first a fan, eventually turned on him too.

Assange’s treatment during the extradition process in the UK has also proved controversial. For champions of press freedom, it has shown the UK in a poor light, pandering to US interests.

Nick Vamos, an expert in extradition law, disagrees. He suggested that a High Court decision this year to allow Assange to appeal may have been instrumental in securing his release.

“Our extradition laws are generous in terms of allowing people to argue different points,” he said. “That is ultimately what has brought everyone to the negotiating table.”